Descriptive statistics:

Python guide (NumPy/Pandas)

Descriptive statistics might seem simple, but they are a daily essential for analysts and data scientists. They allow us to summarise data sets quickly with just a couple of numbers, and are in general easy to explain to others. In this post I’ll briefly cover when to use which statistics, and then focus on how to do them in Python. My approach is to first use just the base functions (so you understand the mechanics), and then show the equivelant functions for two common packages: NumPy (for lists/arrays etc.) and Pandas (for dataframes).

How to select appropriate statistics.

Descriptive statistics fall into two general categories:

- 1) Measures of central tendency which describe a ‘typical’ or common value (e.g. mean, median, and mode); and,

- 2) Measures of spread which describe how far apart values are (e.g. percentiles, variance, and standard deviation).

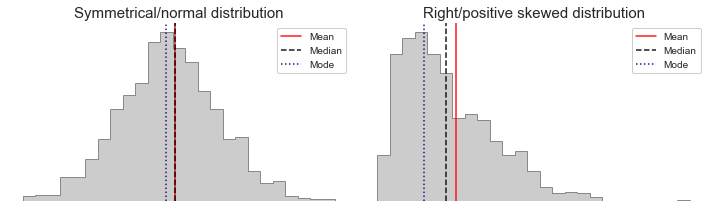

We generally want one of each, but which ones will depend on the distribution of the data. Notice in the image below how the mean is pulled to the right in the skewed distribution, well the same is true for the standard deviation and variance. These statistics sum the values in their calculation, so extremes will impact them. If the distribution is skewed and/or has outliers (e.g. income data), the median and percentiles will give a better representation of the center and spread as they’re less affected. This will become more clear once we work through the formulas below. However, if the distribution is normal, we can use the mean and standard deviation which are more commonly understood, and easier to work with for things like financial calculations and large data sets.

Computing statistics in Python

Now we have an idea of when to use them, I’ll show you the mechanics of how to calculate them with base Python functions. Once you understand how they work, it’s better to use packages like NumPy or Pandas that are optimised and maintained.

These are the packages you’ll need:

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import scipy.stats # used for mode as numpy doesn't have it

Mean (arithmetic):

The sum of the values divided by the number of values (n):

\[\bar{x} = \frac{x_i + \cdots + x_n}{n}\]Base functions:

data = [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 20, 30]

mean_estimate = sum(data) / len(data)

Numpy:

mean_estimate = np.mean(data)

Pandas:

pd_data = pd.DataFrame({'f1': data})

mean_estimate = pd_data.f1.mean()

Note, these will all return the same result: ~11.8.

Median:

The middle value when sorted (the 50th percentile). If the number of values is odd, after sorting we can take the value at the index (n+1)/2:

\[\tilde{x} = X[\frac{n+1}{2}]\]If the number of values is even, after sorting we take the middle two values and average them to get the median:

\[\tilde{x} = \frac {1}{2} \left( X \left[\frac{n}{2} \right] + X \left[{\frac{n}{2} + 1}\right] \right)\]Base functions:

def list_median(sample_list):

"""

Return median value of list using built-in Python functions.

"""

# floor division to get middle value

n = len(sample)

index = n // 2

# Use modulo to get remainder from division by 2: 0 if even, 1 if odd

if n % 2:

# odd: return index, already middle value

return sorted(sample)[index]

# Else, is even, take mean of middle values (index is the upper value so take minus 1 to plus 1 as excludes upper)

return sum(sorted(sample)[index - 1:index + 1]) / 2

data = [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 20, 30]

median_estimate = list_median(data)

Numpy:

median_estimate = np.median(data)

Pandas:

pd_data = pd.DataFrame({'f1': data})

median_estimate = pd_data.f1.median()

Again, these will all return the same result: 9. Note, this is lower than the mean of this data (~11.8). This is because the middle value is not impacted by the last two numbers being notably higher (we only care about the values in the middle). In contrast, the mean takes the sum of the values, so extreme values do impact it. If we add another extreme, say 100, the median is now 9.5 but the mean increases to 20.6.

Mode:

The mode is the most frequently occuring value. E.g. If we have the list [cat, cat, dog, parrot], the mode is cat with a frequency of 2. As you might guess, the mode is useful for nominal (categories e.g. eye color), ordinal (ordered groups e.g. grades), and some interval data (ordered values where differences not equal e.g. temperature).

Base functions:

def list_mode(sample_list):

"""

Return the most frequently occuring value in the list. If there is more than one, return the first encountered.

"""

item_set = set(lst)

item_list = [(item, lst.count(item)) for item in item_set]

max_val = max(item_list, key=lambda a: a[1])

return max_val[0]

mode_value_str = list_mode(['duck', 'duck', 'goose'])

mode_value_int = list_mode([1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5])

Pandas:

samples_pd = pd.DataFrame({'f1': ['duck', 'duck', 'goose'],

'f2': [1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]})

# Returns the mode for each column

print(samples_pd.mode())

NumPy doesn’t have a mode function, but another option is the package scipy. Note, nulls need to be coded correctly to be omitted.

mode = scipy.stats.mode([1, 1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5], axis=0, nan_policy='omit').mode[0]

Variance:

The population variance is the average squared distance of values from the mean:

\[\sigma ^2 = \frac{ \sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n}\]If you’re calculating the variance from a sample, then we divide by n-1 (the degrees of freedom) instead of n:

\[S^2 = \frac{ \sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{(n-1)}\]In small samples, dividing by only n underestimates the variance. Dividing by n-1 increases the variance, particularly in small samples, giving an unbiased* estimator of the population variance. This is called Bessel’s correction. Note, as n increases, the effect of the minus 1 decreases (as the bias also decreases).

* An estimator is unbiased if the expected average error is 0 over many iterations/experiments.

Base functions:

data = [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 20, 30]

squared_differences = [(x - sum(data)/len(data))**2 for x in data]

population_variance = sum(squared_differences)/len(data)

sample_variance = sum(squared_differences)/(len(data) - 1)

Numpy:

# ddof is used in the denominator like this: n-ddof

population_variance = np.var(data, ddof=0)

sample_variance = np.var(data, ddof=1)

Pandas:

data_pd = pd.DataFrame({'f1': data})

population_variance = data_pd.f1.var(ddof=0)

sample_variance = data_pd.f1.var(ddof=1)

Standard deviation:

The standard deviation is the average absolute distance of values from the mean. Which is simply the square root of the variance, so putting it back in the units of the data which is a lot easier to interpret.

\[population: \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{ \sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n}}\] \[sample: s = \sqrt{\frac{ \sum (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{(n-1)}}\]Base functions:

# Repeating the above to get variance

data = [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 20, 30]

squared_differences = [(x - sum(data)/len(data))**2 for x in data]

population_variance = sum(squared_differences)/len(data)

sample_variance = sum(squared_differences)/(len(data) - 1)

population_std_dev = population_variance**0.5

sample_std_dev = sample_variance**0.5

Numpy:

population_std_dev = np.std(data, ddof=0)

sample_std_dev = np.std(data, ddof=1)

Pandas:

data_pd = pd.DataFrame({'f1': data})

population_std_dev = data_pd.f1.std(ddof=0)

sample_std_dev = data_pd.f1.std(ddof=1)

Coefficient of variation (CV):

Another way to use the standard deviation is to express it as a percentage of the mean (i.e. CV = standard deviation/mean). This is used to understand how well the mean represents the full data, with a value <1 considered low variance (mean is a good representation), and values >1 high variance. The CV has no units so it can be used to compare data sets even when the units differ. You can also take the inverse (1/CV), which is called the signal to noise ratio. However, note that it’s sensitive to small changes and approaches infinity when the mean is close to 0.

cv = sample_std_dev/mean_estimate

signal_noise_ratio = 1/cv

Quantiles, quartiles, and percentiles:

Quantiles divide a distribution into equal-sized groups, giving the rank order of values. You might be more familiar with the term percentiles, which are just quantiles relative to 100, e.g. the 75th percentile is 75% or 3/4 of the way up the sorted list of values. A very common way is to split a distribution into 4 groups (quartiles) so that each group has 25% of the values. To achieve this we sort the values and cut at Q1 (25% below), Q2 (50% or the median), and Q3 (75%). You will see these often displayed in a boxplot.

If we have an even number of values, the first quartile is the median of the lower half, and the third quartile is the median of the upper half. However, when we have an odd number of terms (e.g. 1,2,3,4,5,6,7), the quartile calculation gets more complicated and there are different methods to choose from:

- Tukey method: exclude the median (4 in this case). Then Q1=2 and Q3=6.

- M & M method: include the median in both sides. Then Q1=(2+3)/2 = 2.5, and Q3=(5+6)/2=5.5.

- Linear interpolation: take the closest points to the percentile we want to estimate, then assume a straight line between the points and use the slope of the line to estimate the increase in the values per percentile. From that we can calculate the estimated value at any percentile between the points.

The first two methods bias the result one way or the other, so linear interpolation is more commonly used (e.g. in Pandas). I’ll demonstrate below the linear interpolation method for determining any percentile:

Base functions:

# Create sorted values

even_sample = list(np.arange(7, 35, 1))

even_sample_pd = pd.DataFrame({'f1': even_sample})

# The interval between each of n values is 100/(n-1)

interval_size = 100/(len(even_sample_pd)-1)

even_sample_pd['percentile'] = [interval_size * i for i in range(len(even_sample_pd))]

# Slope = increase per percentile = change in values / change in percentiles

# Closest points were: 48.15 = 20 and 51.85 = 21

slope_est = (21-20) / (51.85-48.15)

# Percentile = slope * (target_percent - closest_percent_lower) + lower_value

percentile_50 = 20 + (50 - 48.15)*slope_est

Numpy: Has two related functions, percentile and quantile. The percentile function uses q in range [0,100] e.g. for 90th percentile use 90, whereas the quantile function uses q in range [0,1], so the equivelant q would be 0.9. They can be used interchangeably.

p75_w_percentile = np.percentile(even_sample, q=75, interpolation='linear')

p75_w_quantile = np.quantile(even_sample, q=0.75, interpolation='linear')

Pandas:

p75 = even_sample_pd.quantile(q=0.5, axis=0, numeric_only=True, interpolation='linear')[0]

Interquartile range (IQR)

Related to quartiles, the interquartile range is simply Q3-Q1 (the area shown within the box in a boxplot). It’s worth noting as it’s a common method of defining outliers: points less than Q1 - 1.5IQR or greater than Q3 + 1.5IQR are considered outliers. Given the simplicity, I’ll just demonstrate with NumPy below.

Numpy:

p25 = np.percentile(data_sample_even, q=25, interpolation='linear')

p75 = np.percentile(data_sample_even, q=75, interpolation='linear')

iqr = p75 - p25

Min/max and range:

It can also be useful to check the minimum and maximum values in your data. If these values are very extreme compared to the mean/median, you know you either have a long tail or outliers, and possibly data errors if they are beyond reasonable. The range is then simply the max-min, telling us how far the data stretches.

Base functions:

# 1) Using min/max built in functions

data = [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 20, 30]

min_value = min(data)

max_value = max(data)

# 2) Alternatively, we could sort the list and take first/last

min_value = sorted(data_sample_even)[0]

max_value = sorted(data_sample_even)[-1]

# 3) Without using the base functions (for max just check if values > instead of < current):

def min_in_list(sample_list):

"""

Find the minimum value in a list. Method: Take the first value as the min, then compare each value to the

current min and replace it if it's smaller.

"""

min_value = sample_list[0]

for i in range(len(sample_list)):

if sample_list[i] < min_value:

min_value = sample_list[i]

return min_value

min_value = min_in_list(data)

Numpy:

min_value = np.min(data)

max_value = np.max(data)

Pandas:

data_pd = pd.DataFrame({'f1': data})

min_value = data_pd.f1.min()

max_value = data_pd.f1.max()

Concluding thoughts

Descriptive statistics are a useful tool for summarising large amounts of data. However, remember that very different distributions can have the same descriptive statistics. Think carefully about what you’re trying to understand and why, what mechanisms produce the data, and how you can contextualise or validate the results. A few general things to look out for:

-

Representativeness: Does your sample represent the population of interest? Are there any potential sources of bias? E.g. convenience sampling like gathering data from friends and family is not going to be a good representation of the full population in most cases, as the things which connect you can also effect the outcome of interest (e.g. education, where you live, where you work). A more subtle example would be using data from a set of users who engage with a feature, and expecting new users to behave the same way.

-

Nulls / missing values: Clean up any nulls and other encoded values as they will effect the result and are automatically excluded in some functions. E.g. if null actually means $0, then replace with 0. If null means “unknown” for a categorical variable, you can also use “unknown” as a new level of that category.

-

Outliers: As touched on earlier, if your data has outliers one option is to use statistics that are less sensitive to them e.g. median and percentiles. However, other options include: 1) remove them: only recommended if they’re likely errors (most risky option); 2) replace them: e.g. cap/winsorize the variable so that the top/bottom 1% take the 1st/99th percentile value; or 3) separate them: if the values are coming from some sub-segment of the population that behaves differently, it may be better to split the data and analyse them separately (e.g. business vs regular customers).