Hypothesis testing: Two sample tests for continuous metrics

This post covers the statistical tests I use most often for comparing a continuous metric in two independent samples. In general, I recommend using Welch’s t-test, and if the assumptions are not met, the non-parametric Mann-Whittney u-test may be suitable.

Motivating example

Let’s say we run an e-commerce site. We think that adding a short description to each product on the main page will increase conversion and total profit. So we run an A/B experiment. We take two independent random samples from the population, and show one the new site (with the descriptions). The observed difference in the average profit per visitor is our estimated average treatment effect (i.e. how much we expect profit to change on average per visitor with the new site). However, because we’re taking samples, this estimate will vary each time we repeat the experiment. So when interpreting the result, we need to take into account the uncertainty caused by sampling (i.e. how much it would vary). We do this by considering the size of the effect, relative to the variation in the data. The more variation in the outcome variable, the larger the difference needs to be for us to be confident it’s unlikely just random variation due to sampling.

Below I’ll formalise this process using the hypothesis testing framework.

Hypothesis testing steps

Step 1: Hypothesis

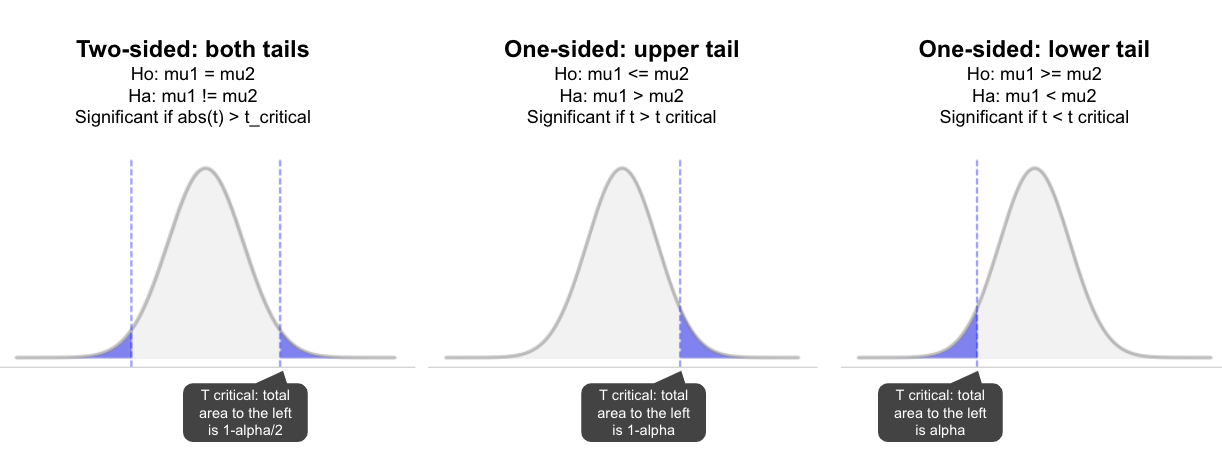

Two-sided test (checking for any difference, larger or smaller):

- Ho: mu1-mu2=0, there is no difference in the means of group 1 and 2

- Ha: mu1!=mu2, there is some difference (not equal)

Alternatively, a one-sided test would look something like (only use if you’re really only interested in differences in one direction, and have good reason to predict a particular direction):

- Ho:mu1 <= mu2, or Ho:mu1 > =mu2

Step 2: Significance

The level of significance (alpha), is the acceptable false positive rate. A common choice is 0.05, which means we expect our test to incorrectly reject the null hypothesis 1/20 times on average (i.e. we conclude there’s sufficient evidence the means are not equal, when there’s actually no difference). The other 95% of the time, we expect to correctly accept the null. The smaller the alpha selected, the larger the sample needed. It’s common to see a larger alpha such as 0.1 in business settings (where more risk is tolerated), and a smaller alpha such as 0.01 in medical settings. Note, there is no significance level that is correct 100% of the time, we always have to trade-off the probability of a false positive, with having enough power to detect an effect when it exists.

If it’s a two sided test, we test whether the difference is positive or negative (both directions). In this case we divide alpha by 2 (e.g. for p=0.05, we use 0.025 on each side), and the result is significant if it’s in the top or bottom 2.5% (unlikely to occur when null is true). For a one-tailed test we put the full 0.05 in one tail and so the result is significant if it’s in that tail. The advantage of one-sided tests is they have more power to detect changes in the hypothesised direction. The disadvantage is they have no statistical power to detect an effect in the other direction. So if you’re unsure about the effect, a two-sided test is recommended. Jim Frost has some very accessible posts on the topic if you’re interested in the opinions on this: One vs two-tailed hypothesis tests, When can I use one-tailed hypothesis tests?.

Step 3: Test statistic

Below we will discuss the specifics, but this is generally calculating the standardised difference between the two groups (relative to the variation in the data). So it’s the same regardless of whether it’s a one or two sided test. We can then look at the sampling distribution under the null to determine how common a value like this (or larger) is, when the null hypothesis is true.

Step 4: p-value

The p-value measures the area under the curve for all values above the test statistic (i.e. for results as large, or larger than this). If it’s very uncommon when the null is true (i.e. less than alpha), we reject the null hypothesis. In this case we conclude it’s unlikely that there is no difference given the data. In the inverse case, p > alpha, we accept the null (we don’t have enough evidence to indicate it’s not true given the data, i.e. we commonly see differences this large by chance when the null is true). Note, this doesn’t mean we have proven the null is true. Either the null is true, or the effect was too small for our test to detect.

Some confuse the p-value as relating to the probability the null or alternate are true, but remember it’s conditioned on the null hypothesis being true:

\[p value = P(\text{observed difference} \:|\: H_\text{o} true)\]Parametric tests for difference in means (assumed distribution):

In general these tests are just comparing the signal (estimated difference) to the noise (variation in the sample). The sample size is important here because a given variance is “noiser” in a small sample then it is in a large sample. More formally, the sampling distribution will become tighter around the true difference as the sample sizes increase (meaning a lower standard error).

General notation:

- \(\bar{x_1}\), \(\bar{x_2}\) are the sample means

- n1,n2 are the sample sizes

- \(s_\text{x1}^2\), \(s_\text{x2}^2\) are the sample variances

- \(\sigma_\text{x1}^2\), \(\sigma_\text{x2}^2\) are the population variances

z-test

Calculates the standardised difference between the means (i.e. the difference in means divided by the standard error for the difference):

\[Z = \frac{\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2}}{\sqrt{\sigma_\text{x1}^2/n1 + \sigma_\text{x2}^2/n2}}\]Assumptions:

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- Assumes the population variances are known and equal (taking a weighted average in the standard error). If the samples are large (>30), the sample variances can be used as estimates.

- Compares the test statistic to the standard normal distribution, so assumes the means follow normal distributions (i.e. the sampling distribution of the estimator is normal).

Note, in practice, the z-test is rarely used and most will use a t-test instead.

t-test:

The t-test was developed by a scientist at Guinness to compare means from small samples (as the z-test is not suitable in this case). It compares the test statistic to the t-distribution instead of the normal distribution. As the t-value increases (standardised difference is further from the center of 0), the less likely it is that the null is true (tail probability decreases), and the smaller the p-value will be. The degrees of freedom controls the shape, increasing the size of the tails when the sample is small, but converging to normal as the sample increases.

\[t = \frac{\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2}}{s_p \sqrt{(\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2})}}\] \[s_p = \sqrt{\frac{(n_1 - 1)s_\text{x1}^2 + (n_2 - 1)s_\text{x2}^2}{n_1 + n_2 - 2}}\]Where \(s_p\) is the pooled sample variance (estimate for population variance \(\sigma^2\)), and \(n_i − 1\) is the degrees of freedom for each group. The total degrees of freedom is the sample size minus two (n1 + n2 − 2). Though the t-statistic does not follow the t-distribution exactly (as variance is estimated for the population), this gives conservative p-values.

Assumptions:

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- Assumes variances are equal (using the sample variances to calculate a pooled estimate of the population variance for the standard error).

- Assumes the means follow normal distributions (i.e. the sampling distribution of the estimator is normal). For small samples, assumes a t-distribution.

In general, the t-test is fairly robust to all but large deviations from these assumptions. However, the equal variance assumption is often violated, so Welch’s t-test (which doesn’t assume equal variance) is more commonly used.

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import t

def ttest(group1, group2, two_tailed=True):

'''

Run two sample independent t-test

group 1, 2: numpy arrays for data in each group

returns: t value, p value

'''

n1 = len(group1)

n2 = len(group2)

var_a = group1.var(ddof=1)

var_b = group2.var(ddof=1)

sp = np.sqrt(((n1-1)*var_a + (n2-1)*var_b) / (n1+n2-2))

t_value = (group1.mean() - group2.mean()) / (sp * np.sqrt(1/n1 + 1/n2))

df = n1 + n2 - 2

if two_tailed:

t_prob = t.cdf(abs(t_value), df)

return t_value, 2*(1-t_prob)

else:

t_prob = t.cdf(t_value, df)

return t_value, 1-t_prob

Using scipy function:

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind

tstat, pval = ttest_ind(group1, group2, equal_var=True, alternative='two-sided')

Welch’s t-test (preferred option)

Welch’s t-test is an adaptation of the t-test which is more reliable when the variance or sample sizes are unequal. Unlike the t-test above, Welch’s t-test doesn’t use a pooled variance estimate, instead using each sample’s variance in the denominator:

\[t = \frac{\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2}}{\sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n2}}}\]The degrees of freedom is also different to the standard t-test (used to determine the t-distribution and thus critical value):

\[dof = \frac {(\frac{s_\text{x1}^2}{n1} + \frac{s_\text{x2}^2}{n2})^2}{\frac{s_\text{x1}^4}{n1^2*(n1-1)} + \frac{s_\text{x2}^4}{n2^2*(n2-1)}}\]Where \(s_\text{x1}^4\), \(s_\text{x2}^4\) are the squared sample variances.

Assumptions:

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- Assumes the means follow normal distributions (i.e. the sampling distribution of the estimator is normal).

Python implementation for Welch’s t-test:

from scipy.stats import t

import numpy as np

def welch_t_test(avg_group1, variance_group1, n_group1,

avg_group2, variance_group2, n_group2, two_tailed = True):

"""

Runs Welch's test to determine if the average value of a metric differs

between two independent samples.

Returns: t value, p value

"""

mean_difference = avg_group2 - avg_group1

mean_variance_group1 = variance_group1/n_group1

mean_variance_group2 = variance_group2/n_group2

se = np.sqrt(mean_variance_group1 + mean_variance_group2)

t_value = mean_difference / se

dof_numer = (mean_variance_group1 + mean_variance_group2)**2

dof_denom = ((mean_variance_group1)**2 / (n_group1-1)) + ((mean_variance_group2)**2 / (n_group2-1))

dof = dof_numer / dof_denom

if two_tailed:

t_prob = t.cdf(abs(t_value), dof)

return t_value, 2*(1-t_prob)

else:

t_prob = t.cdf(t_value, dof)

return t_value, 1-t_prob

np.random.seed(26)

group1 = np.random.normal(46, 3, 100)

group2 = np.random.normal(47, 3.5, 105)

tstat, pval = welch_t_test(avg_group1=np.mean(group1),

variance_group1 = np.var(group1, ddof=1),

n_group1 = len(group1),

avg_group2=np.mean(group2),

variance_group2 = np.var(group2, ddof=1),

n_group2 = len(group2),

two_tailed = True)

print('t value = {:.4f}, pval = {:.4f}'.format(tstat, pval))

Using scipy function:

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind

tstat, pval = ttest_ind(group1, group2, equal_var=False, alternative='two-sided')

Conclusion: default choice is Welch’s t-test

- The t-test was designed for small samples with unknown population variance. However, as the sample increases the t-distribution converges to normal and the degrees of freedom have little effect. Therefore, while the z-test is also suitable for large samples with unknown population variance, the t-test performs equally well (z and t statistic will be very similar) and so it’s preferred for both small and large samples in practice.

- The standard t-test assumes equal variances, meaning the treatment only impacted the means and not the variance (i.e. the distributions should have a similar shape and width). It’s robust to violations if the sample sizes are equal.

- Welch’s t-test doesn’t make this assumption and is robust to unequal variances with and without equal sample sizes. Further, it performs equally well if in fact the sample sizes and/or variance are equal, so it’s prefered in all cases over the standard t-test.

- Note, it’s not recommended to actually test for equal variances and choose the test based on that. This has been shown to increase the false positive rate (type I error), see Delacre et al., 2017 and Hayes and Cai, 2010.

Common issues:

- The central limit theorem (CLT) guarantees conversion to normal for all distributions with finite variance (doesn’t work for power law distributions). However, if the distribution of the observations is non-normal (e.g. skewed, exponential), the speed of convergence might require very large samples for this assumption to be met.

- Outliers: unusual observations far from the mean increase the variance, resulting in a higher standard error in the denominator and lower power (i.e. test statistic will be smaller, all else equal). One option is to winsorize the values first (capping at some percentile).

- For both of the above issues, an alternative is using a non-parametric test which doesn’t assume a certain distribution.

Example of winsorizing in Python. Taking an array of values, this outputs an array with the bottom 1% replaced with the 1st percentile value, and top 1% replaced with the 99th percentile value:

from scipy.stats.mstats import winsorize

df['metric_winsorized'] = winsorize(df['metric'].values(), limits=[0.01, 0.99])

Non-parametric tests for difference in means:

If the assumptions of the parametric tests above are not met, some common non-parametric alternatives are given below. Non-parametric tests don’t assume a distribution.

Mann-Whitney u-test (or Wilcoxon rank sum test)

When the assumptions of the t-test are not met, a non-parametric alternative is the Mann-Whitney u-test. The u-test first combines both samples, orders the values from low to high, and then computes the rank of each value. For tied values, we assign them all the average of the unadjusted rankings (i.e. the unadjusted rank of values [1, 2, 2, 2, 5] is [1, 2, 3, 4, 5], but the values ranked 2-4 are equal so we take the average rank (2+3+4) / 3 = 3, and our ranking becomes [1,3,3,3,5]. As we’re taking the rank instead of the original values, the effect of skew and extreme values is reduced. We then compare the ranked values to see if one sample tends to have higher values or not. If they’re randomly mixed, it suggests the distributions are equal.

The two-sided U statistic is the smaller of U1 and U2, where U1+U2 always equals n1*n2:

\[U_1 = n_1*n_2 + \frac{n_1(n_1 + 1)}{2} - \sum{R_1}\] \[U_2 = n_1*n_2 + \frac{n_2(n_2 + 1)}{2} - \sum{R_2}\]Note:

- U ranges from 0 (complete separation) to n1*n2 (little evidence they differ).

- \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) are the sum of the rank values in samples 1 and 2.

- For large samples (both samples >20), U follows a normal distribution, so we can use a normal approximation to calculate the p-value:

Hypothesis:

Note while the u-test is an alternative to the t-test, they test different hypotheses. Here we test whether the two samples have different distributions (whereas the t-test compares the means):

- Ho: the distributions are equal. It’s equally likely that a randomly selected observation from group 1 will be greater/less than a randomly selected observation from group 2: \(P(A>B) = P(B>A)\).

- Ha: the distributions are not equal. The probability of a random observation from group 1 exceeding a random observation from group 2 is different to the probability of a random observation from group 2 exceeding a random observation from group 1: \(P(X > Y) ≠ P(Y > X)\). Or, equally: \(P(X > Y) + 0.5 · P(X = Y) ≠ 0.5\) (Wikipedia).

- Given the above, we can interpret the p-value as follows: If the samples are from identically distributed populations, how often would we see a difference in the mean ranks as large (or larger) than that observed? For large samples this the normal approximation is used to compute the p-value.

The u-test is a test for stochastic equality (see stochastic ordering), but with stricter assumptions (distributions have similar shape and spread), we can interpret it as a comparison of the medians (Hart, 2001). Therefore, it’s also useful to plot the distributions when interpreting the results.

When to use the u-test?

Given the differences in the hypothesis, it’s important to consider the primary business interests of the test. Some rules of thumb (mostly from Bailey and Jia, 2020):

- The t-test is preferred when the average difference is the primary interest e.g. when we want to make financial decisions based on the average, such as calculating the total uplift in bookings per month expected. In these cases, a trimmed t-test could be used to handle outliers, and variance reduction methods like CUPED can be used to increase sensitivity (power). You might also consider bootstrapping the confidence intervals (resampling with replacement to estimate the sampling distribution).

- If the underlying distribution is close to normal (i.e the t-test is valid), the rank transformation will not provide any improvement in sensitivity and the t-test is generally preferred.

- If we mostly care about whether the majority of users have a better experience, the Mann-Whitney u-test is more suitable e.g. does the change make most users book more frequently? Keep in mind that we don’t measure by how much (which is why t-test is preferred when we need to make financial decisions).

- Another non-parametric option is the two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. It takes the cumulative frequencies, and computes the p-value for the largest difference between the distributions. As a result it’s sensitive to any difference in the distributions, and will detect differences the t-test misses (e.g. when the mean and standard deviation are similar, but there is a difference in the shape). However, for experiment use cases, we generally care about the ‘typical’ experience more than whether there is any difference in the distributions. So the Mann-Whitney u-test is a more common choice.

Assumptions:

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- Values have an order (i.e. we can create a rank). If our metric only takes the values True/False, there is no order, we can’t say True is greater than False.

- There are at least 20 observations in each sample.

Python code:

from scipy.stats import mannwhitneyu

test_stat, p_val = mannwhitneyu(group1, group2, use_continuity=True, alternative='two-sided')

Rank transformation + t-test

An alternative to the above is to rank the data as we do for the u-test, but then apply a standard t-test on the ranked data (comparing the means). It’s been shown this is roughly equivelant to the Mann-Whitney u-test when the sample is large enough (>500 in each sample), Bailey and Jia, 2020. The benefit of this approach is that it’s easier to implement at scale. Experimentation infrastructure commonly has the t-test already implemented, so it only requires a simple transformation of the data.

Python code:

from scipy.stats import rankdata, ttest_ind

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

np.random.seed(26)

group1 = np.random.normal(47, 3, 100)

group2 = np.random.normal(42, 3.5, 105)

df = pd.DataFrame({'sample': [0]*len(group1) + [1]*len(group2),

'values': list(group1) + list(group2)})

df['ranked_values'] = rankdata(df['values'], method='average')

tstat, pval = ttest_ind(df.loc[df['sample']==0]['ranked_values'].values,

df.loc[df['sample']==1]['ranked_values'].values,

equal_var=True)

print('Two sided t-test: t value = {:.4f}, pval = {:.4f}'.format(tstat, pval))

Two sided t-test: t value = 12.8028, pval = 0.0000

Comparing to the u-test results:

from scipy.stats import mannwhitneyu

u_test_stat, u_p_val = mannwhitneyu(group1, group2, use_continuity=True, alternative='two-sided')

print('Two sided Mann-Whitney test: U value = {:.4f}, pval = {:.4f}'.format(u_test_stat, u_p_val))

Two sided Mann-Whitney test: U value = 12.8028, pval = 0.0000

Final thoughts:

- For parametric tests, you should validate your metrics at least once before applying them to make sure the results are valid. See here for more details on how to do this.

- If you’re results are not significant, it could be: 1) the effect (signal) is not large enough; 2) the variance is too high (noise), which is why it’s always good to also plot the distributions (checking for skew, outliers etc.); or, 3) the sample was too small (under-powered).

- We assume for all these tests that the observations are sampled independently (i.e. each observation is independent of the others): they don’t influence each other, each is counted only once, and each is only given one treatment. Some examples where this might not be true:

- 1) if is there is some kind of relationship between the customers (e.g. friends and family, who might discuss the treatment and influence each others outcomes);

- 2) if you can’t be certain that each customer is unique (e.g. tracking by http cookie which could be refreshed, bots, or tracking by different IDs per device with multi-device users); and,

- 3) if supply is shared between the groups (so increased purchases in one group, impacts the ability of the other group to purchase).

Other references:

- Scipy code

- Delacre, M., Lakens, D., & Leys, C. (2017). Why Psychologists Should by Default Use Welch’s t-test Instead of Student’s t-test. International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 92–101.