Causal inference

The primary goal of this guide is to store my notes, but I hope it may also serve as a practical resource for other data scientists in industry. It begins with an intuitive overview of causal effects and the notation commonly used to describe them, then moves through how to define a causal question, assess identifiability, and estimate effects from data using models. While the framework is grounded primarily in potential outcomes, I also make use of causal diagrams (DAGs) to support the discussion on identification.

If you’d like to skip ahead, here are links to some of the key sections:

- Introduction

- Notation

- Causal treatment effects

- Formulating a causal question (estimands and effect measures)

- Identification in randomised experiments

- Identification in observational studies

- Estimating causal effects with models

- ATE models

- CATE models

- Longitudinal challenges and methods

- Other common methods

- Appendix

- References

Introduction

You have likely heard the phrase “correlation is not causation.” Formally, we would say a treatment has a causal effect on an individual if their outcome under treatment differs from what it would have been without it. This includes both active interventions (like sending an email), and passive exposures (like a policy change or app outage). The fundamental problem is that we can never observe both outcomes for the same individual. If you send a customer an email, you can observe whether they return afterward, but you will never know for sure what they would have done without it. The potential outcomes framework makes this explicit by distinguishing between the factual (observed outcome) and the counterfactual (unobserved alternative). While we can’t observe both for one individual, we can estimate the average treatment effect (ATE) across groups, provided the treated and untreated are otherwise comparable. Further, by conditioning on relevant variables, we can estimate the conditional average treatment effect (CATE), enabling more personalised decisions.

In randomised experiments, comparability is achieved by design. By randomly assigning treatment, we ensure that differences in outcomes between treated and untreated groups can be attributed to the treatment. However, experiments are not always feasible due to legal, ethical, financial, or logistical constraints. In such cases, we rely on observational data, and distinguishing causation from correlation becomes more difficult. When two variables are associated, observing the value of one, tells us something about the value of the other. However, observing two variables X and Y moving together cannot tell us whether X causes Y, Y causes X, or whether both are caused by a third variable Z. To use a classic example, beer and ice cream sales may rise together in summer, not because one causes the other, but because both are driven by temperature.

Causal inference from observational data requires careful thinking about the data-generating process: defining an intervention (treatment), understanding how treatment is assigned, and clarifying assumptions. For any method to identify causal effects, three core conditions must hold: a well-defined intervention (something concrete needs to be changing), exchangeability (treated and untreated groups are comparable in the absence of treatment), and positivity (every individual has a nonzero probability of receiving each treatment level).

Ultimately, causal claims from observational data rely heavily on domain knowledge and the plausibility of the assumptions. Since perfect data is rare, transparency and sensitivity analyses are essential for assessing potential biases. This transparency is both a strength and a vulnerability, as it invites scrutiny. However, relying on methods with hidden or unacknowledged assumptions does not lead to more trustworthy decisions; it only conceals the uncertainty rather than addressing it.

Description, Prediction, or Explanation?

Before jumping into causal inference theory and methods, it’s crucial to understand where causal questions fit within the broader data science landscape. As a data scientist, you’re often handed vague requests. A critical part of the job is to clarify what the stakeholder is really asking, and what they intend to do with the answer. Most questions fall into one of three broad categories:

-

Descriptive: What is happening? E.g. Where are our users located? What is our market share by region?

Descriptive analysis summarises data to understand current or past conditions, reporting observed patterns without implying causality. The key validity issues are: measurement error (variables recorded inaccurately), and sampling error (the data does not represent the intended population, e.g. survey results can suffer from selection bias).

-

Predictive: What is likely to happen? E.g. Who will churn next month? Which users are likely to convert?

Predictive models use historical patterns to forecast unknown or future outcomes. Their goal is predictive accuracy, evaluated on new data. Variables are chosen based on their ability to improve prediction, regardless of whether they cause the outcome. Predictive models can be used to help rank or segment, but do not tell you which actions will change outcomes. The main validity issues are overfitting and target leakage (resulting in poor out of sample performance).

-

Explanatory (i.e. causal inference): Why did something happen? What would happen if we changed something? E.g. What drives conversion? Would offering a 5 percent discount increase trial conversion rates?

Causal analysis estimates the effect of an intervention or treatment on an outcome, answering what-if questions to guide decision-making. It requires assumptions about the data-generating process, often informed by domain knowledge. The central validity concern is internal validity: whether the estimated effect is credible for the studied group. Though external validity also matters when generalising findings beyond the sample. Unlike predictive models, causal models may not predict outcomes well but provide unbiased estimates of treatment effects when assumptions hold.

Confusion often arises in real-world projects when questions span multiple categories. You might start with descriptive analysis to identify patterns and understand your population, build predictive models to forecast outcomes, and ultimately tackle causal questions about how to influence results. The common mistake is treating these categories as interchangeable. Even when using the same tools, the assumptions, goals, and interpretations differ. Crucially, a model with high predictive accuracy does not necessarily reveal the true effect of any variable. Conversely, a model designed for causal estimation may not excel at prediction. These are fundamentally different tasks.

To illustrate this point, suppose you build a model to predict beer sales, and find that ice cream sales are a strong predictor. The model performs well and the coefficient is significantly positive, so you conclude that increasing ice cream sales will also increase beer sales. However, the true driver is likely weather. Acting on this mistaken belief could waste time, or even reduce overall sales if the two products compete. It is easy to make this mistake. Predictive models often produce convincing results that seem to explain outcomes. When stakeholders want actionable insights, there is pressure to move quickly and skip formal causal analysis. As a result, we often get what Haber et al. (2022) calls “Schrödinger’s causal inference”: an analysis that avoids stating a causal goal, but still makes causal claims and recommendations.

While it often requires more upfront effort, more formal causal thinking prevents teams from pursuing strategies that have no real effect, saving time in the long run by avoiding costly detours.

Choosing the Right Level of Evidence

Causal thinking promotes a deeper understanding of problems by focusing on mechanisms and clarifying assumptions. However, not every causal question requires a full formal study. In many operational settings, a strong correlation paired with contextual knowledge is enough to justify quick action. For example, if conversions drop suddenly and you notice a product change was deployed at the same time, it’s reasonable to suspect the change as the cause and test a rollback. In these cases, you are still reasoning causally, but the cost of being wrong is low, and the response is reversible. The key is to be honest about the level of uncertainty and the type of evidence being used. As a counter example, suppose you’re evaluating whether the company should expand to a new market. Let’s say prior expansions were successful, but focused on high-growth regions. Naively comparing this market to the prior examples may overestimate the expected outcome. The decision is high cost and difficult to reverse, so it would be beneficial to use a more formal causal approach to control for the market differences.

Workflow

The distinction between prediction and causation naturally leads us to the workflow for explanatory questions. If you’ve done a lot of predictive modeling, this will feel familiar, but with some important shifts in mindset. In causal inference, our goal isn’t just to model outcomes well, but to estimate what would happen under different interventions. That means clearly defining counterfactual scenarios and ensuring that our models reflect the underlying data-generating process, rather than aiming for high predictive accuracy.

The workflow below outlines one principled approach to identifying causal effects, though it’s not the only path:

-

1. Specify a causal question: Start by clearly articulating your causal question in terms of an intervention and outcome. For example: What is the effect of weekly promotional emails on time to unsubscribe? This step includes defining the estimand (e.g. average treatment effect on survival at 12 weeks), population, and time horizon.

-

2. Draw assumptions using a causal diagram: Use a diagram (e.g. DAG) to encode your assumptions about the relationships among treatment, outcome, covariates, and possible sources of confounding or bias. This helps identify which variables must be adjusted for to estimate the causal effect.

-

3. Model assumptions: Choose a method that aligns with your causal goal and the structure of your data. Crucially, your model should reflect the causal structure from the DAG, not just predictive performance.

-

4. Diagnostics: Once fit, evaluate how well the models reflect your assumptions. This could involve checking covariate balance after weighting, evaluating model fit and positivity violations, or plotting predicted survival curves under different interventions. Unlike pure prediction, model diagnostics in causal inference focus on plausibility and identifiability, not predictive accuracy metrics.

-

5. Estimate the causal effect: With a well-specified and diagnosed model, compute your causal estimand. This may involve simulation of counterfactual outcomes, and bootstrapping confidence intervals.

-

6. Conduct sensitivity analysis: All causal estimates rest on untestable assumptions (e.g., no unmeasured confounding). Sensitivity analyses help quantify how robust your conclusions are to violations of those assumptions. This might include bounding approaches, bias formulas, or varying model specifications.

I’m presenting this workflow upfront to provide a clear framework for how the pieces fit together. In the next sections, we’ll dive into the theory and notation behind each step, but having the full picture in mind will help keep the details grounded.

Notation

Before we go further, let’s cover some notation and definitions. This will make it easier to follow the explanations, but you can refer back as you go. Note, capital letters are used for random variables, and lower case for particular values of variables.

| Notation / Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| \(T_i\) | Treatment indicator for observation \(i\). Takes the value 1 if treated, 0 if not treated. |

| \(Y_i\) | The observed outcome for observation \(i\). |

| \(Y_{\text{0i}}\) | The potential outcome for observation \(i\) without treatment (i.e., counterfactual under control). |

| \(Y_{\text{1i}}\) | The potential outcome for observation \(i\) with treatment (i.e., counterfactual under treatment). |

| \(Y_{\text{1i}} - Y_{\text{0i}}\) | The individual treatment effect for observation \(i\). This is not directly observable. |

| \(ATE = E[Y_{\text{1}} - Y_{\text{0}}]\) | The average treatment effect (ATE): the expected treatment effect across the entire population. |

| \(ATT = E[Y_{\text{1}} - Y_{\text{0}} \mid T=1]\) | The average treatment effect on the treated (ATT): the expected effect for those who actually received treatment. |

| \(\tau(x) = E[Y_{\text{1}} - Y_{\text{0}} \mid X = x]\) | The conditional average treatment effect (CATE): the expected effect for individuals with covariates \(X = x\). |

| \(\perp\!\!\!\perp\) | Denotes independence. For example, \(A \perp\!\!\!\perp B\) means that variables \(A\) and \(B\) are statistically independent. |

If \(T_i = t\), then \(Y_\text{ti}=Y_i\). That is, if observation i was actually treated (t=1), their potential outcome under treatment equals their observed outcome. Meanwhile, \(Y_t\) denotes the random variable representing the potential outcome under treatment t across the entire population.

An introduction to causal treatment effects

Individual effect

A treatment has a causal effect on an individual’s outcome if their outcome with the treatment differs to their outcome without it. Let’s pretend we have two identical planets, and the only difference is that on Earth 1 no one plays tennis (\(Y^\text{t=0}\)) and on Earth 2 everyone plays tennis (\(Y^\text{t=1}\)). The outcome is whether you get cancer, and the treatment is playing tennis. The table below shows there is a causal effect of tennis on cancer for Alice, Bob and Eva because the difference in the potential outcomes is non-zero. Alice and Eva get cancer if they don’t play tennis, and don’t get cancer if they do. The inverse is true for Bob.

| Name | \(Y^\text{t=0}\) | \(Y^\text{t=1}\) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alice | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Bob | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Charlie | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| David | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Eva | 1 | 0 | -1 |

| Fred | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Average | 3/6 | 2/6 | -1/6 |

Average effect

If we take the average treatment effect in the example above (\(ATE=-\frac{1}{6}\)), we would conclude tennis decreases the chance of you getting cancer. We can also see this in the average cancer rate for those with and without treatment (as the average of the differences is equal to the difference of the averages). With tennis (\(Y^\text{t=1}\)) they had a \(\frac{2}{6}\) chance, whereas without it (\(Y^\text{t=0}\)) they would have had a \(\frac{3}{6}\) chance (\(E[Y^\text{t}] \neq E[Y^\text{t'}]\)). Keep in mind there can be individual causal effects even if there is no average causal effect. For example, Alice has an individual causal effect because she avoids cancer if she plays tennis, even if the average showed no difference. While the average causal effect is most commonly used, you can also use other differences such as the median or variance.

The fundamental problem

The fundamental problem of causal inference is that we can never observe the same person/observation with and without treatment at the same point in time. While we might not be able to measure individual effects, we can measure average effects. This is where potential outcomes comes in: the actual observed outcome is factual and the unobserved outcome is the couterfactual. If we compare those with and without treatment and they are otherwise similar, we can estimate the average effect.

| Name | \(Y^\text{t=0}\) | \(Y^\text{t=1}\) |

|---|---|---|

| Alice | 1 | ? |

| Bob | ? | 1 |

| Charlie | 1 | ? |

| David | ? | 0 |

| Eva | ? | 0 |

| Fred | 0 | ? |

| Average | 2/3 | 1/3 |

Now in our two Earth’s example, if we randomly selected the samples, this would be an unbiased estimate of the average causal effect. However, if we just took a sample of people from our one Earth and compared those who played tennis to those who don’t, we run into the problem of bias because all else is not equal (there are other factors influencing the cancer rate that also impact the likelihood of playing tennis, i.e. confounders). We can say from this there’s an association, but not necessarily causation.

Bias in observational data

Bias is the key concept that separates association from causation. Intuitively, when we compare observational data, we will consider why a difference might exist that isn’t due to the treatment itself. For instance, playing tennis requires time and money, which means tennis players may also have higher incomes and engage in other health-promoting behaviors, such as eating healthy food, and having regular doctor visits. This could explain some or all of the observed difference in cancer rates.

We cannot observe the counterfactual outcome, \(Y_0\), for the tennis group. In other words, we can’t know what their cancer risk would be if they didn’t play tennis. However, we can reason that \(Y_0 \mid T=1\) (the cancer risk of tennis players if they didn’t play tennis) is likely lower than \(Y_0 \mid T=0\) (the cancer risk of non-tennis players), implying that the baseline differs (it’s not a fair comparison). Using the potential outcomes framework we can express this mathematically. An association is measured as the difference in observed outcomes:

\[E[Y \mid T=1] - E[Y \mid T=0] = E[Y_1 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\]We can separate the treatment effect (ATT) and the bias components by first adding and subtracting the counterfactual outcome \(E[Y_0 \mid T=1]\) (the outcome for treated individuals had they not received the treatment):

\[E[Y \mid T=1] - E[Y \mid T=0] = E[Y_1 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=0] + E[Y_0 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=1]\]Then re-arranging the equation:

\[= E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid T=1] + E[Y_0 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\]Where:

- \(E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid T=1]\) represents the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT), i.e. the treatment effect for those who received the treatment (tennis players).

- \(E[Y_0 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\) represents the bias, which is the difference between the potential outcomes of the treated and untreated groups before the treatment was applied. This reflects pre-existing differences (e.g. higher income, healthier lifestyle) that can affect the outcome.

In our tennis example, we suspect that \(E[Y_0 \mid T=1] < E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\), meaning that tennis players, even without tennis, may have a lower cancer risk than non-tennis players. This bias will likely underestimate the true causal effect of tennis on cancer rates. Note, this was an example of confounding bias, but later we will cover other sources of bias.

Addressing the bias

To obtain an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect, we need the treated and untreated groups to be exchangeable before the treatment is applied (\(E[Y_0 \mid T=1] = E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\), so the bias term becomes 0). In this case, the difference in means can give us a valid causal estimate for the Average Treatment Effect on the Treated (ATT):

\[ATT = E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid T=1]\] \[= E[Y_1 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=1]\] \[= E[Y_1 \mid T=1] - E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\] \[= E[Y \mid T=1] - E[Y \mid T=0]\]If the treated and untreated groups are expected to respond to the treatment similarly (exchangeable), then we can assume that the treatment effect is the same for both groups. In that case:

\[E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid T=1] = E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid T=0]\] \[ATT = E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid T=1] = ATE\]This is the goal of causal inference: to remove bias so we are left with a consistent estimate of the estimand.

Formulating a causal question

A well-defined causal question begins with a clear decision context: What intervention is being considered? What outcome are you trying to influence? And for whom? These questions help define the unit of analysis, the treatment, the outcome, and the target population. Once this is clear, we can formulate the question more precisely.

Estimands

We often refer to the average treatment effect (ATE), which is the expected difference in outcomes if everyone received treatment versus if no one did. However, the ATE is just one example of an estimand you might target. To clarify the terminology:

| Consideration | Why it matters | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Estimand | Defines the “who” and “what” of the causal question (for example, ATE, ATT). | The causal effect you want to learn about, the target quantity or “who” and “what” of the question. |

| Effect measure | Specifies how the effect is quantified (for example, difference in means, odds ratio). | How you express or quantify the effect, the scale or metric used. |

| Estimator | Describes the method or algorithm used to estimate the effect from data. | Your method or algorithm for estimating the effect from data. |

| Estimate | The actual numerical result you compute, subject to sampling variability. | The numerical result you get, which can vary due to sampling and randomness. |

To make this more relatable, consider this analogy: the effect measure is the type of cake you want to bake (chocolate, carrot, etc.), the estimand is the perfect picture of the cake in the cookbook, the estimator is the recipe, and the estimate is the cake you actually bake, complete with cracks, uneven frosting, or oven quirks.

Example

Different estimands target different populations or conditions. For example, if you’re offering a 20% personalised discount to customers, are you interested in its impact on all customers, only those who received it, or specific subgroups like frequent shoppers? We can consider different estimands depending on the business goal in this case:

| Estimand | Description | Use Case | Business Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATE (Average Treatment Effect) | Effect averaged over the entire population. | Evaluating broad rollout potential | What is the average impact of offering a 20% discount across all customers? |

| ATT (Average Treatment Effect on the Treated) | Effect among those who actually received the treatment. | Evaluating past campaign performance | How effective was the discount among those who received it? |

| ATC (Average Treatment Effect on the Controls) | Effect among those who did not receive the treatment. | Expanding treatment to new customers | What is the expected effect if we applied the discount to previously untreated customers? |

| CATE (Conditional Average Treatment Effect) | Effect conditional on covariates or subgroups (e.g. high spenders). Estimates average effects in subgroups; often used as a proxy for Individual Treatment Effects (ITEs) | Designing personalised or segmented campaigns | How much more effective is the discount for frequent shoppers compared to occasional ones? |

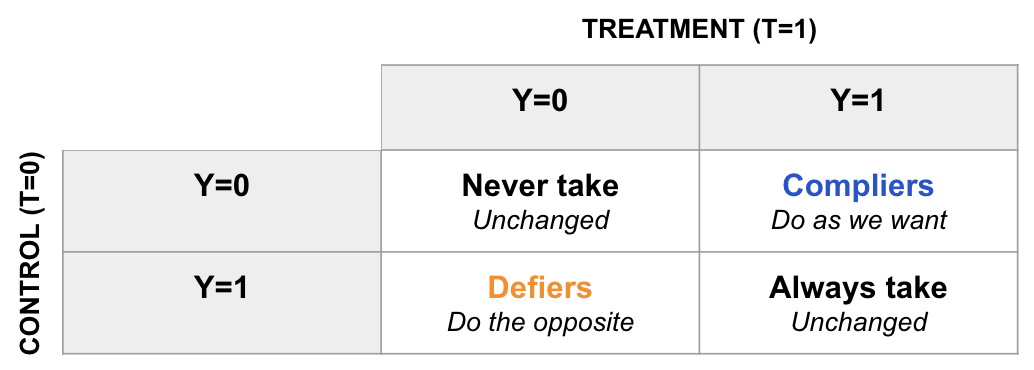

| LATE (Local Average Treatment Effect) | Effect among compliers (those whose treatment is influenced by an instrument, e.g. randomized assignment). | Using natural experiments or A/B tests with imperfect adherence | What is the effect of the discount on customers who redeem it (when randomly assigned to receive one)? |

| QTE (Quantile Treatment Effect) | Effect at specific outcome quantiles. Captures heterogeneity beyond the mean. | Detecting tail effects (e.g. high-value or low-value shifts) | How does the discount affect different points in the spend distribution (e.g. light vs. heavy spenders)? |

| Policy Value | Expected outcome under a treatment assignment rule (e.g. treat only high-CATE users). | Making decisions based on targeting models | What is the impact of using a targeting strategy based on predicted treatment effects? |

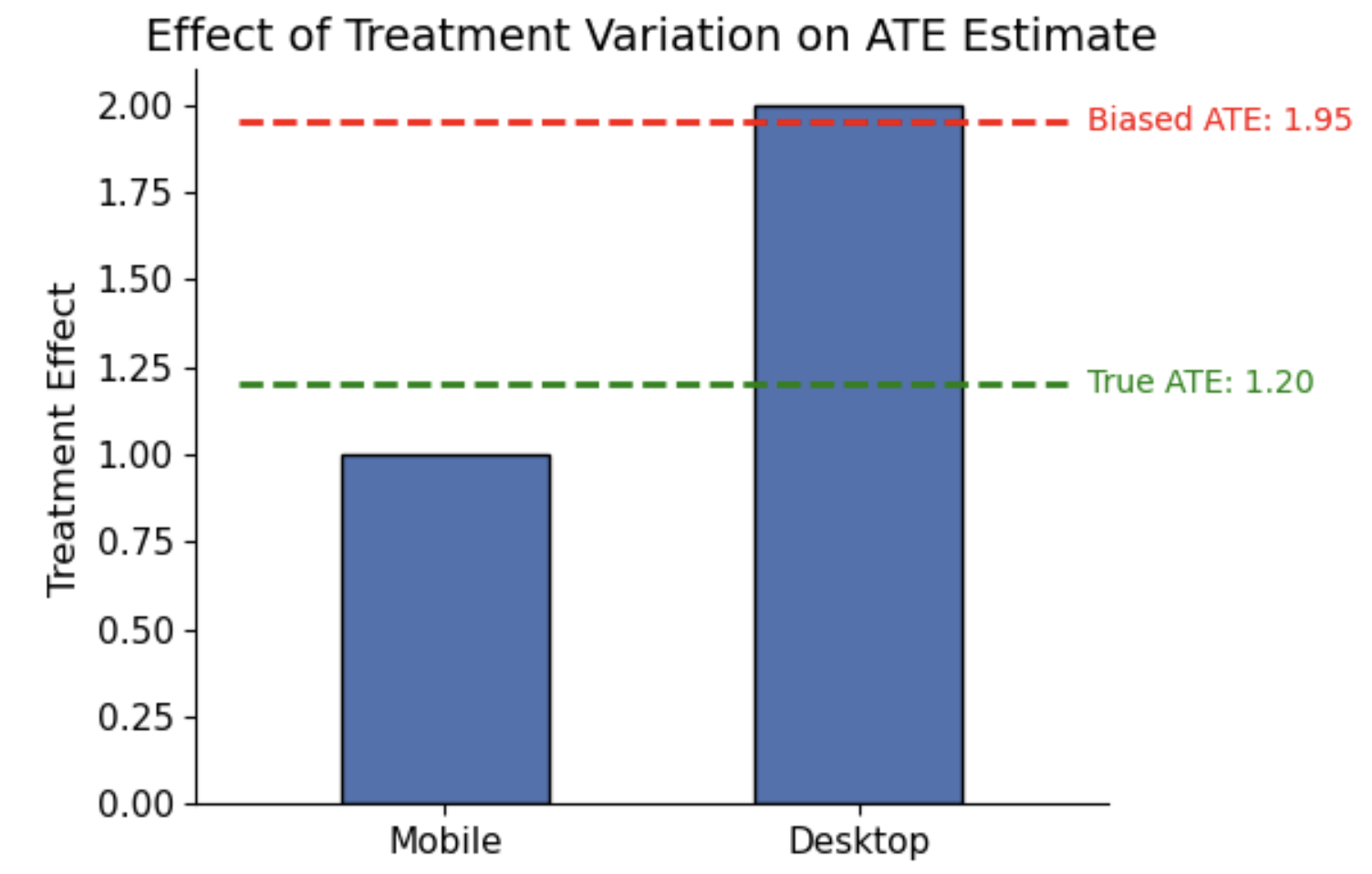

Implicit target

In practice, it can be unclear which estimand your chosen estimator actually targets. Different estimation methods implicitly assign different weights to subgroups within your data, which influences whether your estimate reflects the average treatment effect (ATE), the effect on the treated (ATT), or another causal quantity. For example, linear regression often produces a weighted average of subgroup effects, but the weights depend on the distribution of treatment and covariates in your sample. Even in a random sample, if some groups show more treatment variation or have larger sample sizes, they may receive more weight, causing the estimate to reflect their treatment effect more than the overall ATE. Additionally, negative weights may appear, indicating extrapolation beyond the observed data and potentially reducing the validity of the estimate. Examining these implied weights can help clarify the causal interpretation of your estimate and ensure it aligns with your decision context and causal question.

Effect measures

Once you’ve defined the estimand, the next decision is how to express the size of the effect. That is, the effect measure. This determines the scale of the estimate, which influences both interpretation and communication. In most cases, you’re comparing expected potential outcomes under treatment (\(E[Y_1]\)) and control (\(E[Y_0]\)). The ATE, for instance, uses an additive scale:

\[\text{ATE} = E[Y_1 - Y_0] = E[Y_1] - E[Y_0]\]But other scales, such as ratios or log-transformed differences, may be more appropriate depending on the outcome type or audience. Sticking with the discount example we can show how different effect measures apply to binary (purchase) and continuous (spending) outcomes:

| Outcome Type | Difference (Additive) |

Ratio (Relative) |

Multiplicative (Log or Odds-based) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Absolute difference in outcome between treatment and control groups. | Relative (proportional) change due to treatment. | Nonlinear transformations of effect. Often used when scale is skewed or to stabilize variance. |

| Binary Outcome Did the customer purchase? |

$\text{Risk Diff} = \Pr(Y_1 = 1) - \Pr(Y_0 = 1)$ “The discount increases purchase likelihood by 10 percentage points.” |

$\text{Risk Ratio} = \frac{\Pr(Y_1 = 1)}{\Pr(Y_0 = 1)}$ “Customers with the discount are 1.5× more likely to buy.” |

$\text{Odds Ratio} = \frac{\frac{\Pr(Y_1 = 1)}{1 - \Pr(Y_1 = 1)}}{\frac{\Pr(Y_0 = 1)}{1 - \Pr(Y_0 = 1)}}$ “The odds of purchase double with the discount.” |

| Continuous Outcome How much did the customer spend? |

$\text{Mean Diff} = E[Y_1] - E[Y_0]$ “Average spend increases by $5 with the discount.” |

$\text{Ratio of Means} = \frac{E[Y_1]}{E[Y_0]}$ “Discounted customers spend 1.2× more on average.” |

$\log\left(\frac{E[Y_1]}{E[Y_0]}\right)$ or $\frac{E[Y_1] - E[Y_0]}{E[Y_0]} \times 100\%$ “Spend increases by 20% with the discount.” |

Note: Recall that \(Y_t\) is the random variable representing the potential outcome under treatment \(t\) across the entire population.

When choosing an effect measure:

- Use difference measures when you’re interested in the absolute change caused by treatment. These are intuitive for outcomes measured in natural units (e.g. dollars, percentage points).

- Use ratio measures when the relative size of the effect is more meaningful than the absolute difference, particularly when outcomes vary widely across individuals or groups.

- Use log or odds-based measures when dealing with multiplicative effects, skewed outcomes, or when the event is rare. Odds are mathematically convenient and tend to be more stable than probabilities near 0 or 1. However, they are often harder to interpret for non-technical stakeholders.

Summary

Estimands define the target of your analysis: the causal effect you’re trying to learn about, for a specific population under specific conditions. Whilst effect measures define the scale used to express that effect, which influences how results are interpreted, compared, and communicated. Choosing the right estimand and effect measure is a foundational part of causal inference, ensuring your findings directly answer the right question.

Once you’ve defined these, the next challenge is figuring out how to identify that causal quantity from data. In randomised experiments, identification is usually straightforward: treatment is independent of potential outcomes by design. But with observational data, identifying a causal effect requires careful reasoning about causal structure, specifically, which variables to adjust for, and which to leave alone. Therefore, we’ll start with a brief section on Randomised Control Trials, and then spend a lot more time on observational data.

Causal identification in randomised experiments

In a Randomised Control Trial (RCT) there are still missing values for the counterfactual outcomes, but they occur by chance due to the random assignment of treatment (i.e. they are missing at random). Imagine flipping a coin for each person in your sample: if it’s heads, they get the treatment; if it’s tails, they get the control. Since the assignment is random, the two groups (treatment and control) are similar on average, making them exchangeable (i.e. the treatment effect would have been the same if the assignments were flipped). This is an example of a marginally randomised experiment, meaning it has a single unconditional (marginal) randomisation probability for all participants (e.g. 50% chance of treatment with a fair coin, though it could also be some other ratio).

The potential outcomes in this case are independent of the treatment, which we express mathematically as: \(Y_t \perp\!\!\!\perp T\). You could convince yourself of this by comparing pre-treatment values of the two groups to make sure there’s no significant difference. Given the expected outcome under control, \(E[Y_0 \mid T=0]\), is equal to the expected outcome under control for those who received treatment, \(E[Y_0 \mid T=1]\), any difference between the groups after treatment can be attributed to the treatment itself: \(E[Y \mid T=1] - E[Y \mid T=0] = E[Y_1 - Y_0] = ATE\).

It’s important not to confuse this with the statement: \(Y \perp\!\!\!\perp T\) which would imply that the actual outcome is independent of the treatment, meaning there is no effect of the treatment on the outcome.

Conditional randomisation & standardisation

Another type of randomised experiment is a conditionally randomised experiment, where we have multiple randomisation probabilities that depend on some variable (S). For example, in the medical world we may apply a different probability of treatment depending on the severity of the illness. We flip one (unfair) coin for non-severe cases with a 30% probability of treatment, and another for severe cases with a 70% probability of treatment. Now we can’t just compare the treated to the untreated because they have different proportions of severe cases.

However, they are conditionally exchangeable: \(Y_t \perp\!\!\!\perp T \mid S=s\). This is to say that within each subset (severity group), the treated and untreated are exchangeable. It’s essentially 2 marginally randomised experiments, within each we can calculate the causal effect. It’s possible the effect differs in each subset (stratum), in which case there’s heterogeneity (i.e. the effect differs across different levels of S). However, we may still need to calculate the population ATE (e.g. maybe we won’t have the variable S for future cases). We do this by taking the weighted average of the stratum effects, where the weight is the proportion of the population in the subset:

\[Pr[Y_t=1] = Pr[Y_t = 1 \mid S =0]Pr[S = 0] + Pr[Y_t = 1 \mid S = 1]Pr[S = 1]\] \[\text{Risk ratio} = \frac{\sum_\text{s} Pr[Y = 1 \mid S=s, T=1]Pr[S=s]}{\sum_\text{s} Pr[Y = 1 \mid S=s, T=0]Pr[S=s]}\]This is called standardisation, and conditional exchangeability is also referred to as ignorable treatment assignment, no omitted variable bias or exogeneity.

Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW)

Mathematically, this is the same as the process of standardisation described above. Each individual is weighted by the inverse of the conditional probability of treatment that they received. Thus their weight depends on their treatment value T and the covariate S (as above, which determined their probability of treatment): if they are treated, then the weight is \(1 / Pr[T = 1 \mid S = s]\); and, if they are untreated it’s: \(1 / Pr[T = 0 \mid S = s]\). To combine these to cover all individuals we use the probability density function instead of the probability of treatment (T): \(W^T = 1 / f[A \mid L]\). Both IPW and standardisation are controlling for S by simulating what would have happened if we didn’t use S to determine the probability of treatment.

Challenges

Even in a randomised experiment, certain issues can threaten the validity of causal conclusions. One foundational assumption in causal inference is the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA). It has two components: 1) no interference between units: one individual’s outcome does not depend on the treatment assigned to others; and, 2) well-defined treatments: each unit receives a consistent version of the treatment, with no hidden variation. Two common violations of SUTVA are interference and leakage:

| Aspect | Interference | Leakage of Treatments |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | When an individual’s outcome is influenced by the treatment or behavior of others. | When individuals in the control group (or other non-treatment groups) receive some form of treatment. |

| Context | Common in social networks, product launches, team-based incentives, or any setting with interaction between units. | Common in experiments or rollouts where treatment access is imperfectly controlled or shared across users. |

| Impact on Counterfactuals | The counterfactual is not well-defined because an individual’s outcome depends on others’ treatments (violates SUTVA). | The counterfactual can still be defined, but it becomes biased due to treatment contamination (may violate SUTVA). |

| Cause | Results from interactions between individuals (e.g., peer effects, social contagion, team dynamics). | Results from imperfect treatment assignment or adherence to protocols (e.g., non-compliance or treatment spillover). |

| Example | A user’s likelihood of subscribing may depend on whether their friends or coworkers were also targeted with the offer. | I send you a discount offer, and you forward it to a friend who was assigned to the control group. |

| Effect on Treatment Effect | Makes it difficult to estimate treatment effects due to non-independence of outcomes. | Dilutes the treatment effect, making it harder to assess the true effectiveness of the treatment. |

| Type of Problem | A structural problem in defining counterfactuals due to interdependence between individuals. | A practical problem with treatment implementation, leading to contamination between groups. |

Analysis risks

Even with perfect randomisation at the design stage, careless analysis can break the assumptions we rely on to draw valid causal conclusions. The issues below are some of the most common ways experiment results get distorted in practice:

- Post treatment bias: Conditioning on variables that are measured after treatment assignment can lead to biased effect estimates. This happens either by blocking part of the treatment effect (if the variable lies on the causal path from treatment to outcome, i.e. a mediator), or by inducing selection bias (if the variable is influenced by both treatment and other variables related to the outcome, i.e. a collider). It’s an easy mistake to make when dashboards or experimentation tools let you filter by any feature, without clearly showing whether that feature is pre or post treatment. For example, if you run an experiment on a new recommendation algorithm and filter results based on user engagement (which is affected by the treatment), you break randomization. The filtered groups are no longer comparable, and any observed differences may reflect selection bias rather than the true treatment effect.

- Randomisation and analysis unit mismatch: If you randomise on one unit (e.g. user ID) but analyse on another (e.g. session or page view), the treatment and control groups may no longer be exchangeable. This can introduce bias and lead to variance inflation, especially if outcomes are correlated within the randomisation unit. For example, if you randomise by user but compute conversion per session, and the treatment affects session frequency, you’re conflating treatment effects with exposure differences, invalidating the comparison and overstating precision.

- Multiple testing: Exploring many outcomes, metrics, or segments increases the chance of false positives simply by random variation. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t explore, but it does mean you should interpret significance with care. Even with no true effect, some differences will appear statistically significant at the 95% level just by chance. Correcting for multiple comparisons (e.g. Bonferroni, Benjamini-Hochberg) or using wider confidence intervals helps mitigate this. If the analysis is exploratory, clearly label it as such and avoid over-interpreting noisy differences.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but it highlights a key point: randomised experiments aren’t magical, you can still break randomization if you’re not careful.

Crossover Experiments

While less common in industry, it’s worth mentioning a special case where we can observe both potential outcomes for each individual, by assigning them to different conditions at different times. For example, we might give a user the treatment at time $t = 0$ and the control at time $t = 1$, then compare their outcomes across those periods to estimate an individual-level treatment effect. This design is called a crossover experiment, and it can, in theory, eliminate between-subject variation entirely. However, for this approach to yield valid causal estimates, several strong assumptions must hold:

- No carryover effects: The treatment effect must end completely before the control period begins. In other words, the treatment should have an abrupt onset and a short-lived impact.

- No time effects: The outcome should not change systematically over time due to learning, trends, fatigue, or other temporal factors.

- Stable counterfactuals: The counterfactual outcome under no treatment should remain the same across time periods.

In practice, these assumptions can be difficult to justify. For example, a user exposed to a new recommendation algorithm may change their behavior in a lasting way, making it difficult to observe a clean post-treatment control condition. Still, in tightly controlled settings where these assumptions are plausible, such as short-session A/B tests of user interface changes, crossover designs can offer high efficiency by letting individuals serve as their own control.

Causal identification in observational studies

Randomised experiments are considered the gold standard in causal inference because they eliminate many sources of bias by ensuring treatment is assigned independently of potential outcomes. However, they’re not always feasible or ethical. In many industry settings, constraints related to time, data infrastructure, or business needs make it difficult to run a proper experiment, or to wait for long-term outcomes. For instance, suppose you’re testing a new user onboarding experience. You can run an A/B test for two weeks, but maybe what you really care about is its impact on user retention six months later. Long-term experiments often face practical limitations: users may churn or become inactive before the outcome is observed, tracking identifiers like cookies or sessions may not persist long enough to follow users over time, and business pressures may require decisions before long-term data is available.

In such cases, we turn to observational data. The advantage is that it’s abundant in most businesses. The challenge is that treatment is not assigned at random, so treated and untreated groups may differ in ways that affect the outcome. These differences, called confounding, can bias our estimates of causal effects. For example:

- Users who receive promotional emails may already be more engaged than those who don’t, even before the email is sent.

- Tennis players who choose to switch racquets mid-season may differ in skill, injury status, or motivation from those who don’t.

- Customers who opt into a premium plan may have higher spending behavior unrelated to the plan itself.

To identify causal effects from observational data, we need to make assumptions and apply adjustment techniques to account for such confounding. The rest of this guide focuses on helping you navigate the choices and interpret causal estimates responsibly, even when randomisation isn’t available.

Identifiability conditions

To estimate causal effects with observational data, we often assume that treatment is conditionally random given a set of observed covariates (S). Under this assumption, the causal effect can be identified if the following three conditions hold:

1. Consistency: The treatment corresponds to a well-defined intervention with precise counterfactual outcomes. This overlaps with the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA), which adds the requirement of no interference between units, meaning one individual’s treatment does not affect another’s outcome. Vague or ill-defined treatments undermine consistency. Examples:

- Comparing the risk of death in obese versus non-obese individuals at age 40 implicitly imagines an unrealistic, instantaneous intervention on BMI. Since such an intervention is not feasible, the observed outcomes cannot meaningfully represent the counterfactuals. A better-defined intervention might involve tracking individuals enrolled in a specific weight loss program over time.

- Grouping together different marketing exposure points (e.g. email, push notifications, and banner ads) into a single “treatment” makes it unclear what intervention is being evaluated.

2. Exchangeability (also called ignorability): Given covariates S, the treatment assignment is independent of the potential outcomes. In other words, all confounders must be measured and included in S. If this is the case, then within each level of S, the distribution of potential outcomes is independent of treatment: \(Y_t \perp\!\!\!\perp T \mid S = s\). If important confounders are unmeasured, causal estimates may be biased. Since there’s no statistical test for exchangeability, defending it relies on domain expertise and thoughtful variable selection. This is often the hardest condition to justify in industry settings. Example:

- Online businesses can typically measure user behavior, past purchases, and some demographics, but unmeasured factors like activity with competitors, personal life events, or attitudes toward the brand may still influence both treatment and outcome.

3. Positivity (also called overlap): Every individual must have a non-zero probability of receiving every level of treatment, given S. That is, within each covariate-defined subgroup, there must be both treated and untreated individuals. Positivity violations can sometimes be addressed by redefining the population of interest using exclusion criteria, but this reduces generalisability and should be explicitly acknowledged. Examples:

- If all severely ill patients are always treated, we cannot compare treated and untreated outcomes within that subgroup.

- If every user who reaches a checkout page is shown a discount, there’s no untreated group to compare within that segment.

While consistency and positivity are often manageable with careful study design and clear definitions, exchangeability typically requires more substantive domain knowledge and careful attention to potential confounding.

When assumptions fail

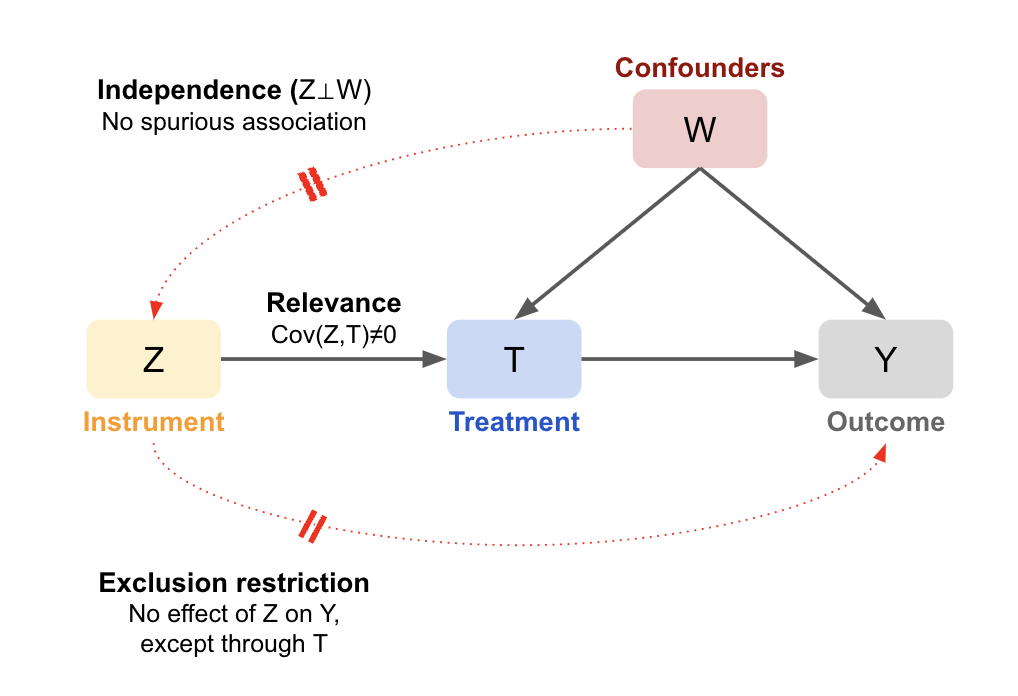

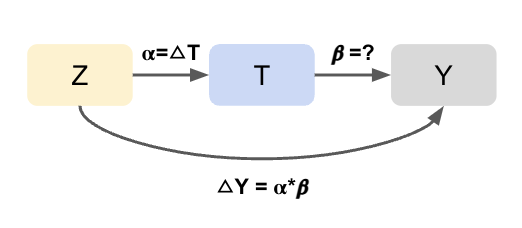

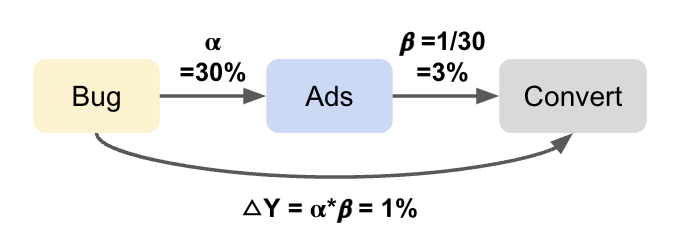

If these assumptions do not hold, all is not lost. There are alternative strategies that can help recover causal estimates under weaker or different sets of assumptions. For example, Instrumental Variable (IV) analysis leverages a variable that influences treatment assignment but does not directly affect the outcome (and is not related to unmeasured confounders). This can help achieve exchangeability in situations where confounding cannot be fully addressed through adjustment alone, effectively mimicking random assignment. These methods are covered in later sections.

Target Trial

A useful approach for framing a causal question is to first design a hypothetical randomised experiment, often called the target trial. This imagined experiment helps clarify exactly what causal effect we want to estimate and what conditions must hold to identify it from observational data. The target trial forces you to specify key components: the treatment or intervention, eligibility criteria, the assignment mechanism, and the outcome. Once these are defined, you can assess whether your observational data is rich enough to emulate the trial. For example, do you have sufficient information to identify who would be eligible? Can you determine treatment assignment timing? If your emulation is successful, the causal effect estimated from observational data should correspond to the causal effect in the target trial.

This thought experiment is particularly useful for evaluating the core assumptions required for identification:

- Consistency: By clearly defining the intervention in your target trial, you ensure that observed outcomes under a given treatment assignment can be interpreted as the corresponding counterfactual outcomes.

- Exchangeability: Once you specify the assignment mechanism in the target trial, you can reason more clearly about whether treatment assignment in the observational data is independent of potential outcomes given observed covariates.

- Positivity: The trial framework helps identify cases where some groups could never receive a certain treatment.

If a target trial cannot be specified, then any associations observed in the data may still be useful for generating hypotheses but they cannot be interpreted as causal effects without stronger assumptions or alternative identification strategies.

Causal Graphs

Representing assumptions visually can further enhance understanding and communication. By mapping variables and their causal relationships (including unmeasured variables), causal graphs help you reason about which variables need adjustment. Typically, these graphs are drawn as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). Each variable is represented as a node, and arrows (or edges) between nodes indicate causal relationships, usually flowing from left to right. With just two variables, we would say they are independent if there is no arrow between them (for example, the outcomes of rolling two random dice). Keep in mind, graphs show relationships that apply to any individual in the population. Although uncommon, it’s possible that the average effect or association is not observed in a sample, such as when positive and negative effects perfectly cancel each other out.

As more variables are added, it becomes important to consider the possible paths between them and whether those paths are open or blocked. The key principle is that any variable is independent of its non-descendants conditional on its parents. This means that once you know the variables that directly cause it (its parents), the variable does not depend on any other earlier variables that are not in its direct line of influence (its non-descendants). If all paths between two variables are blocked once we control for other variables, then those variables are conditionally independent. For example, a user’s likelihood of canceling a subscription might be independent of their reduced feature usage once we know their overall satisfaction score, as satisfaction explains both behaviors, leaving no additional link.

Understanding how and why paths are blocked or open leads us to the next key concept: the types of paths that exist in a causal graph and how they affect identifiability.

Key Causal Pathways

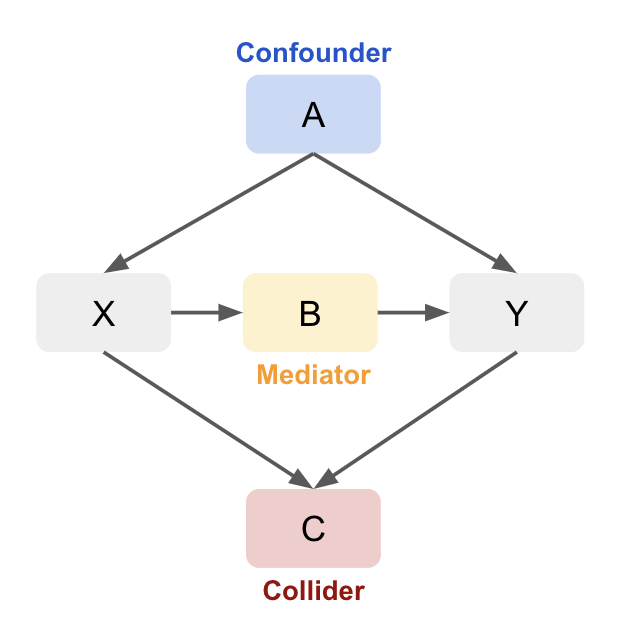

There are three key types of paths to look for: mediators, confounders, and colliders.

1. Mediator: A variable that lies on the causal path from treatment to outcome, capturing part or all of the effect of treatment.

Conditioning on a mediator helps clarify the mechanism by which one variable affects another. Consider a situation where Sales are influenced by both Ad Spend and Web Traffic:

\[\text{Ad Spend} \rightarrow \text{Traffic} \rightarrow \text{Sales}\]Here, increasing Ad Spend increases Traffic, which in turn boosts Sales. If we condition on Traffic, the relationship between Ad Spend and Sales disappears because Traffic fully mediates (explains) this relationship. Mathematically:

\[S \perp \perp A \mid T\]If we fit a regression model without considering traffic, we might mistakenly conclude there’s a direct relationship between ad spend and sales. Once traffic is included, ad spend might no longer be statistically significant, as its effect on sales is mediated by traffic. We might therefore want to optimise ad spend to maximise traffic, using a separate model to predict the effect of the increased traffic on sales. However, if we wanted to estimate the total effect of ad spend on sales, we wouldn’t want to control for traffic as this blocks the indirect path (underestimating the total).

2. Confounder: A variable that causally influences both the treatment and the outcome, potentially introducing spurious correlation if not controlled.

A variable that causes two other variables. Conditioning on this variable is necessary to avoid a spurious association between the two other variables, biasing the causal effect estimate. Imagine that Smoking has a causal effect on both Lung Cancer and Carrying a Lighter:

\[\text{Lighter} \leftarrow \text{Smoking} \rightarrow \text{Lung Cancer}\]While carrying a lighter doesn’t cause lung cancer, if we compare lung cancer rates between people who carry a lighter and those who don’t, we might find a spurious association. This happens because smoking influences both lung cancer and carrying a lighter. To avoid bias, we must condition on smoking, breaking the spurious link between carrying a lighter and lung cancer (\(Lighter \perp \perp Lung Cancer \mid Smoking\)).

In a sales example, if both ad spend and sales increase during the holidays due to seasonality (Ad Spend ← Season → Sales), failing to control for the season could lead to overstating the effect of ad spend on sales.

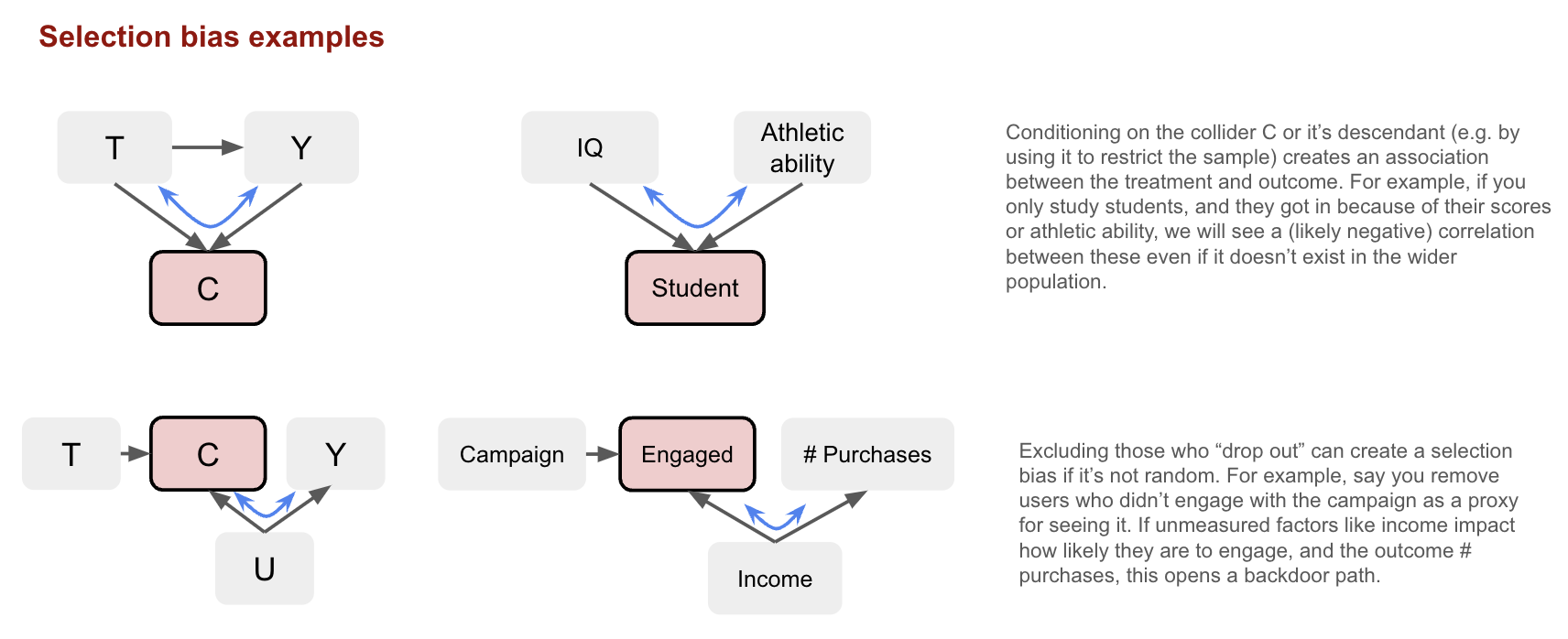

3. Collider: A variable that is caused by two or more other variables, opening a non-causal path if conditioned on.

Be cautious not to condition on a collider as it can create a spurious relationship between the influencing variables by opening a non-causal path between treatment and outcome (collider bias). In this example, both Ad Spend and Product Quality affect Sales, but they are independent of each other:

\[\text{Ad Spend} \rightarrow \text{Sales} \leftarrow \text{Product Quality}\]Once we condition on sales, we create a spurious association between ad spend and product quality (\(Ad Spend \perp \perp Product Quality\) but \(Ad Spend \not\perp Product Quality \mid Sales\)). When sales are high, both ad spend and product quality may be high, and when sales are low, both may be low. This creates a false impression that ad spend directly improves product quality, even though both only influence sales.

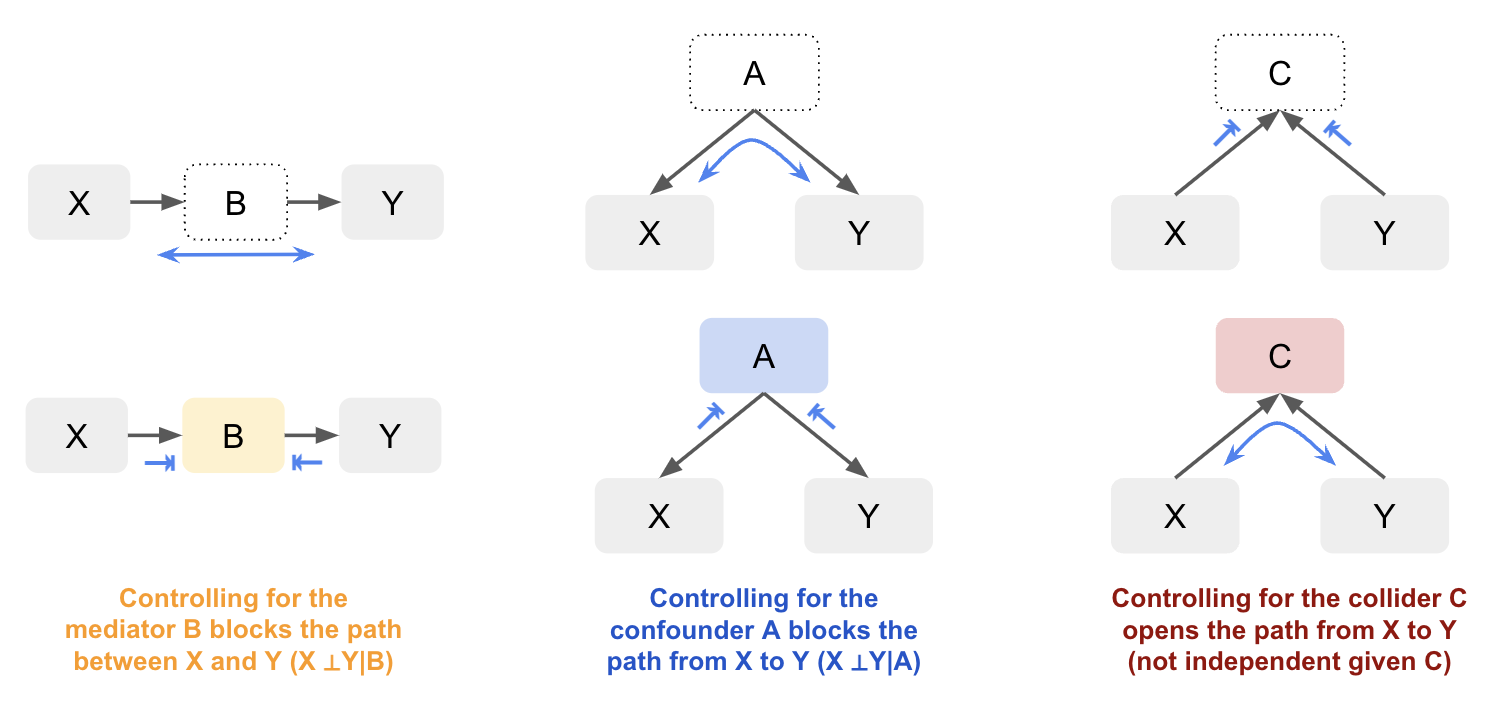

General Rules

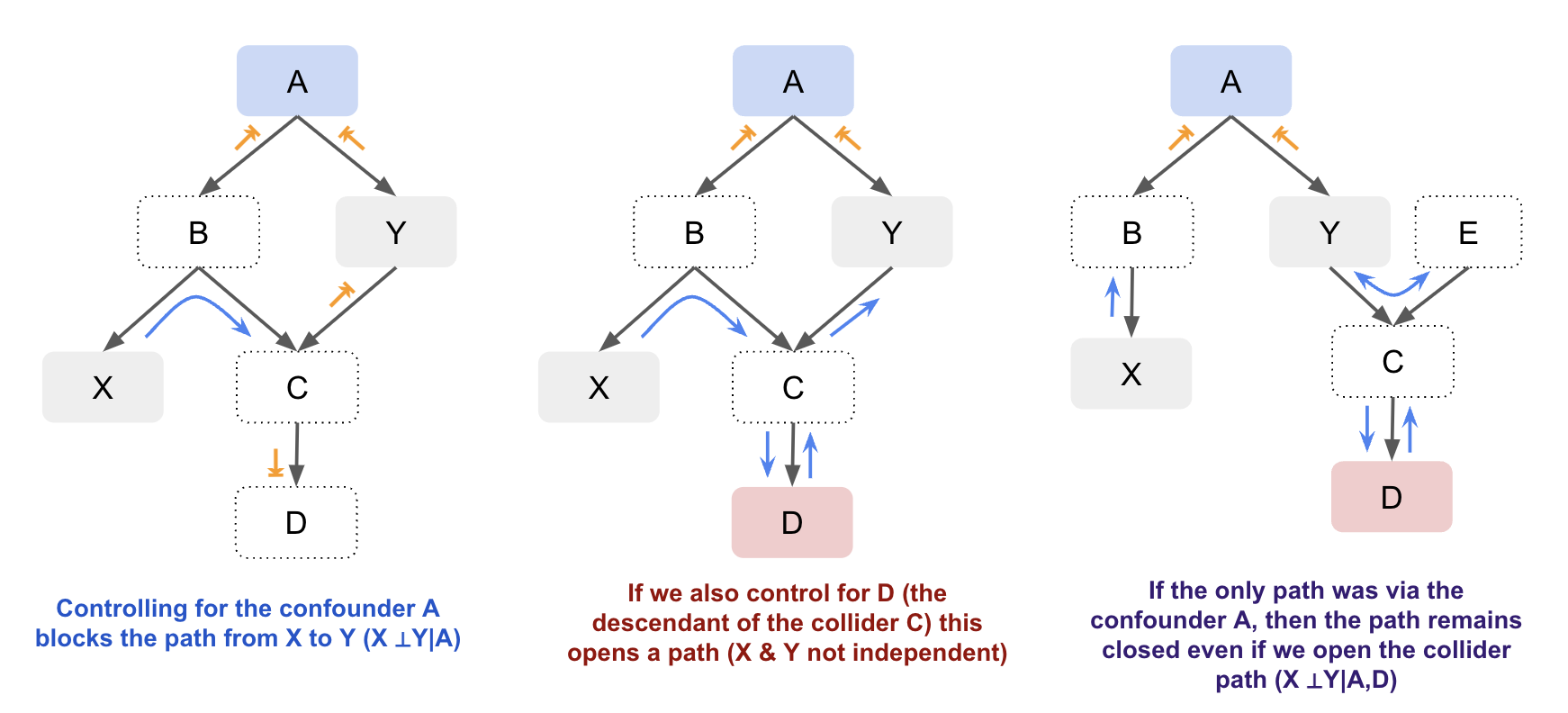

Conditioning on non-colliders (confounders or mediators) blocks the path, making the other variables independent. Conditioning on a collider (or its descendants) creates a dependency between the variables influencing it, which opens the path. Not conditioning on the collider blocks the path, keeping the influencing variables independent.

By visualising causal relationships in a graph, you can better understand how variables are connected and whether observed associations are due to direct causal effects, confounding, mediation, or colliders. By distinguishing between these different relationships, we can handle them appropriately to have more accurate models and inference. While you don’t always need a graph, as the number of variables involved increases it can make it easier to manage. For example, let’s look at just a slightly more complex graph with both confounders and colliders. By visualising the graph it’s easier to identify whether X and Y are independent based on whether there’s an open path between them:

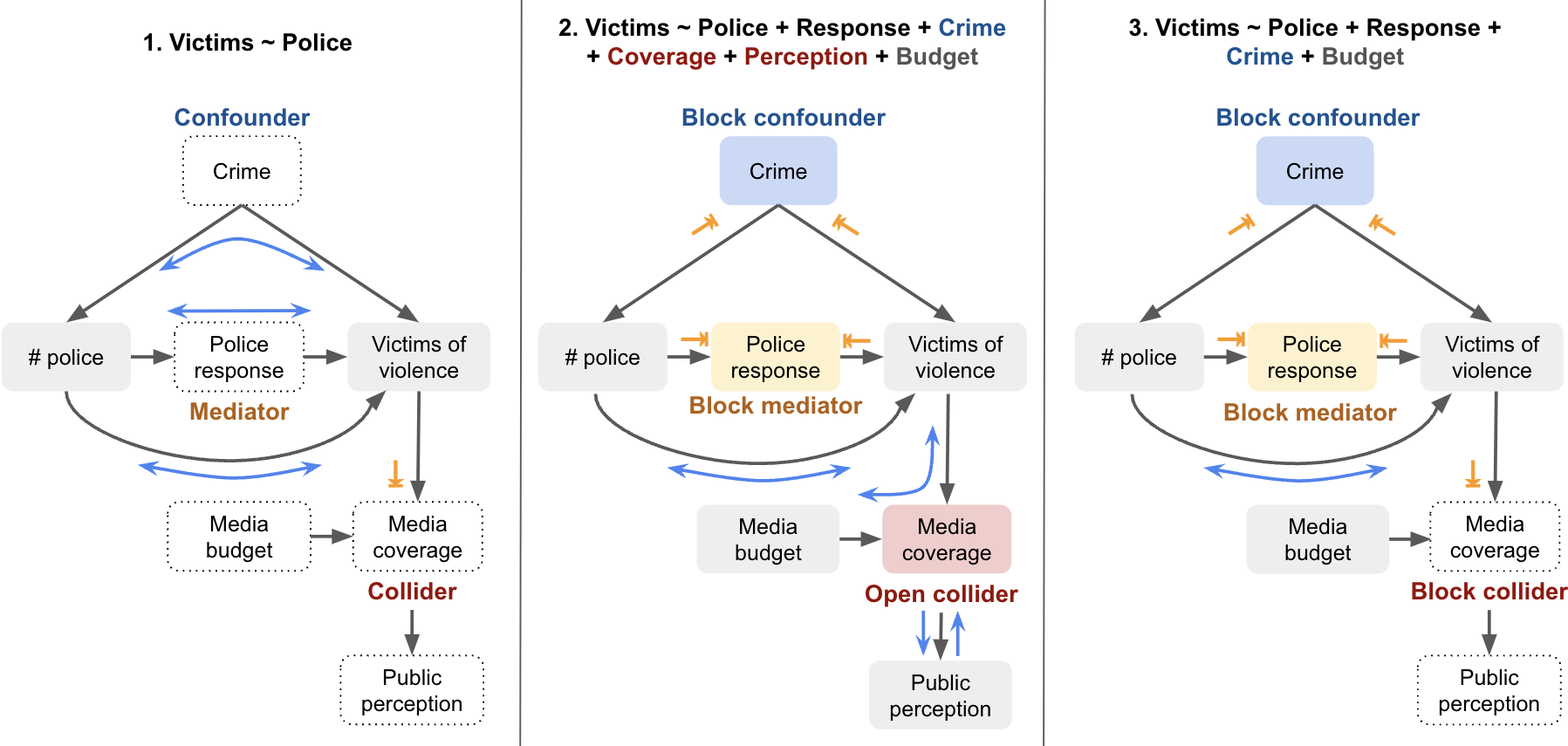

Let’s look at a labelled example. Suppose we want to understand the direct causal relationship between the number of police officers and the number of victims of violent crimes in a city. Depending on what variables we control for, we open different paths and will get different results:

| Model | Variables Included | Notes |

|---|---|---|

1. Victims ~ Police |

Only treatment (Police) | Doesn’t control for confounder (Crime), so may yield biased results (e.g. more police associated with more crime). Mediator (Response) not controlled, so overestimates direct effect. |

2. Victims ~ Police + Response + Crime + Coverage + Perception + Budget |

Treatment, mediator, confounder, and collider path | Opens a backdoor path via collider (Media Coverage), which can create a spurious association between Police and Budget. If both are influenced by a common cause (e.g. City Budget), this can bias the estimate. |

3. Victims ~ Police + Response + Crime + Budget |

Treatment, mediator, confounder, and irrelevant variable | Avoids collider bias by excluding Media Coverage. Including Budget is unnecessary but not harmful unless it reintroduces bias through other unblocked paths. |

Note, if we wanted to measure the total effect of the number of police on the number of victims, we would only control for the confounder in this case, as the mediator would absorbs some or all of the effect.

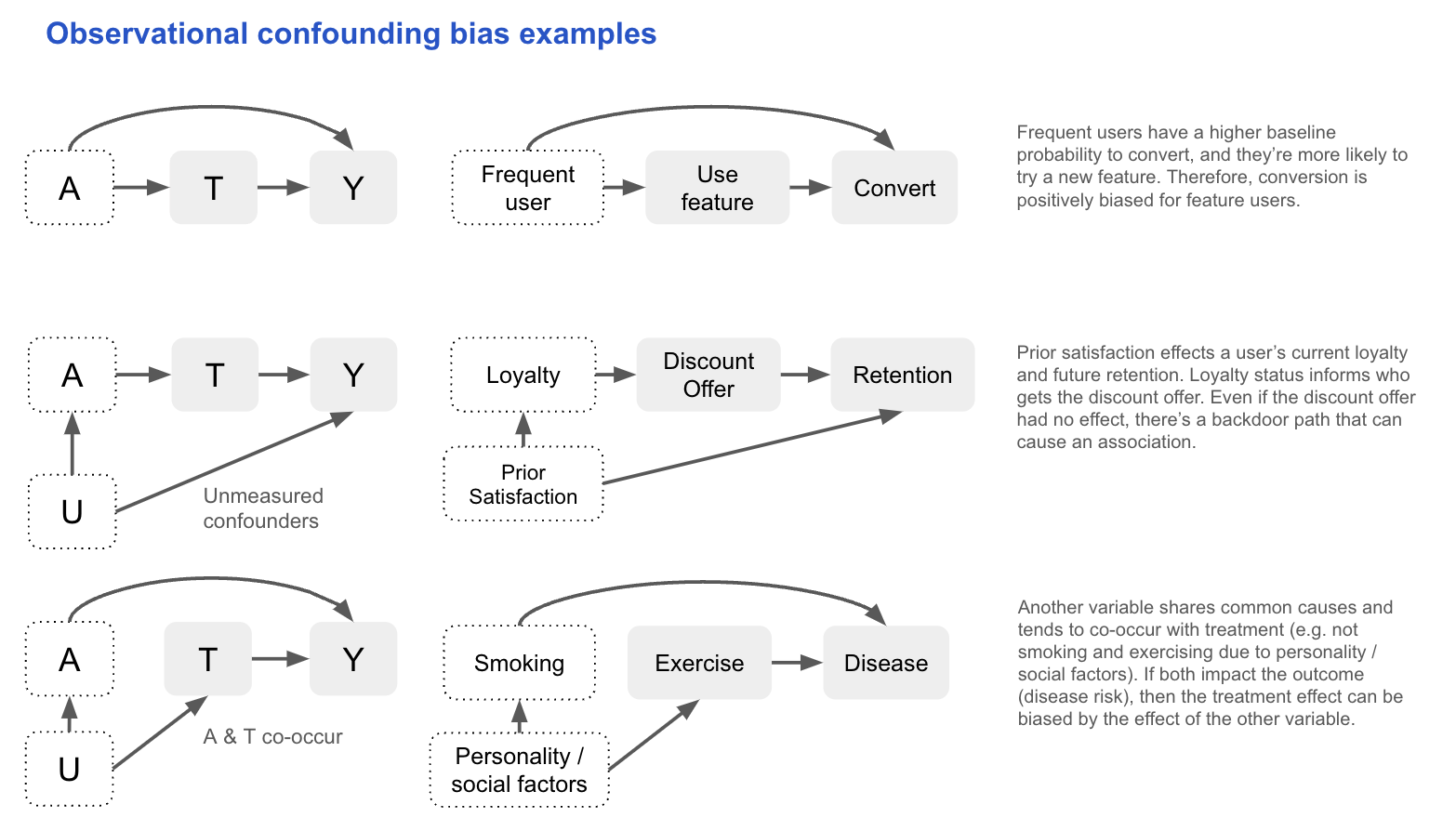

Systematic bias

Let’s revisit the concept of bias, this time with the help of causal graphs. Systematic bias occurs when an observed association between treatment and outcome is distorted by factors other than the true causal effect. In graphical terms, this often corresponds to open non-causal paths linking treatment and outcome, producing spurious associations even when the true effect is zero (sometimes called bias under the null). Common causes, or confounders, create backdoor paths that induce such spurious associations, while conditioning on common effects, or colliders, opens other non-causal paths and leads to selection bias. Measurement error in confounders or key variables can also contribute by preventing complete adjustment. Additionally, systematic bias can arise from other sources like model misspecification or data issues, which affect the accuracy of effect estimates. In this section, we’ll focus on confounding and collider bias, which can be clearly illustrated using causal graphs.

Confounding bias

In observational studies, treatment is not randomised and so it can share causes with the outcome. These common causes (confounders) open backdoor paths between treatment and outcome, creating spurious associations. If you don’t control for them, the observed relationship can reflect both the causal effect of treatment and the effect of these confounders.

If we know the causal DAG that produced the data (i.e. it includes all causes shared by the treatment and outcome, measured and unmeasured), we can assess conditional exchangeability using the backdoor criterion:

All backdoor paths between T and Y are blocked by conditioning on A, and A contains no variables that are descendants of T.

In practice, this assumption is untestable, so we often reason about the likely magnitude and direction of bias:

- Large bias requires strong associations between the confounder and both treatment and outcome.

- If the confounder is unmeasured, sensitivity analysis can test how results change under varying assumptions about its effect size.

- Surrogates for unmeasured confounders (e.g. income for socioeconomic status) can partially reduce bias, though they can’t fully block a backdoor path.

Other methods have different unverifiable assumptions to deal with confounding. Difference-in-Differences (DiD) can be used with a negative outcome control (e.g. pre-treatment value of the outcome) to adjust for confounding. For example, if studying Aspirin’s effect on blood pressure, pre-treatment blood pressure (C) isn’t caused by the Aspirin (A), but shares the same confounders (e.g. pre-existing heart disease). Differences in C between the treatment groups gives us an idea of the bias in the Aspirin–blood pressure (Y) relationship (assuming the confounding effect is the same).

\[E[Y_1 - Y_0 \mid A = 1] = \left( E[Y \mid A = 1] - E[Y \mid A = 0] \right) - \left( E[C \mid A = 1] - E[C \mid A = 0] \right)\]Ultimately, the choice of adjustment method for confounding depends on which assumptions are most plausible. With observational data, uncertainty is unavoidable, so being explicit about assumptions and using sensitivity tests to quantify the potential bias allows others to critically assess your conclusions in a productive way.

Selection bias

Selection bias refers to bias that arises when individuals or units are selected in a way that affects the generalisability of the results (i.e. it’s not representative of the target population). Here we focus on selection bias under the null, meaning there will be an association even if there’s no causal effect between the treatment and the outcome. This occurs when you condition on a common effect of the treatment and outcome, or causes of each. For example, when observations are removed due to loss to follow up, missing data, or individuals opting in/out:

This can arise even in randomised experiments. Conditional-on-Positives (CoPE) bias occurs when analysis is restricted to “positive” cases for a continuous outcome. For instance, splitting “amount spent” into a participation model (0 vs >0) and a conditional amount model (>0) ignores that treatment can shift people from zero to positive spending. The spenders in treatment and control then differ systematically, and comparing them yields the causal effect plus selection bias

\[E[Y_0 \mid Y_1 > 0] - E[Y_0 \mid Y_0 > 0]\]Typically, control spenders look inflated (negative bias), as those who spend only because of treatment spend less than habitual spenders. We need to account for the fact that treatment affects both the participation decision (whether someone spends anything) and the spending amount (conditional on spending).

Other than design improvements, selection bias can sometimes be corrected with weights (e.g. via Inverse Propensity Weighting). As with confounding, we should also consider the expected direction and magnitude of the bias to understand the impact.

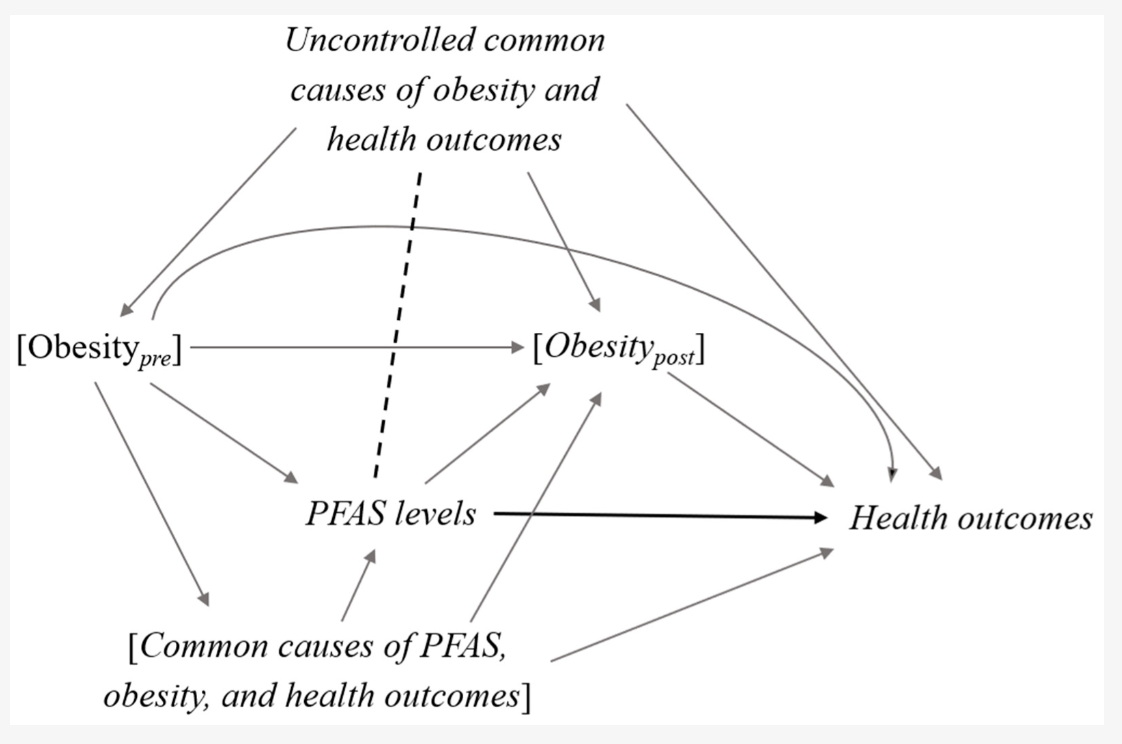

Example: graphs in the wild

The relationships between variables in causal models can be much more complex in reality, making it challenging to identify the role of each variable. This is especially true when the time ordering of variables is unclear. Let’s consider the graph below looking at the causal effect of PFAS levels on health outcomes, controlling for obesity both before and after exposure:

Source: Inoue et al., 2020

Source: Inoue et al., 2020

In the graph, we see a bi-directional relationship between obesity and PFAS levels:

- Pre-obesity (obesity before PFAS exposure) can cause higher PFAS levels because PFAS accumulate in fat tissue. Additionally, obesity itself is associated with worse health outcomes. Therefore, obesity_pre is a confounder because it affects both PFAS levels and health outcomes.

- PFAS exposure may also increase the risk of developing obesity (e.g. due to endocrine disruption or metabolic changes). In this case, obesity_post (obesity after PFAS exposure) is a mediator, as it is part of the causal pathway from PFAS exposure to health outcomes.

- Obesity, PFAS levels, and health outcomes share common causes, such as dietary and lifestyle factors. These factors can affect both obesity and PFAS levels, and so they are also confounders.

To estimate the total effect of PFAS exposure on health outcomes, we want to control for confounders but avoid controlling for mediators, as doing so would block the indirect effect of PFAS on health outcomes via obesity. This is where the issue arises because both obesity and PFAS levels are cumulative measures (i.e. they reflect long-term, prior exposure). Most studies only measure obesity at baseline, and the temporality between PFAS exposure and obesity is not clear. The authors of this graph note that conditioning on obesity_post (post-PFAS exposure) could:

-

- Close the mediating path, thus underestimating the total effect of PFAS on health outcomes; and,

-

- Introduce collider bias, opening a backdoor path between PFAS levels and health outcomes via the uncontrolled common causes of obesity_post (shown by the dotted line in the graph), potentially leading to spurious associations.

They suggest not stratifying on obesity status if it’s likely a mediator of the PFAS-health relationship being studied (as the stratum effects could be biased). On the other hand, it’s generally safe to adjust for the common causes of PFAS and obesity (e.g. sociodemographic factors, lifestyle, and dietary habits) because these factors are less likely to act as mediators in this causal pathway. This is just one example, but it highlights the need to carefully consider the causal graph, and not over-adjust in ways that could bias the causal effects. When you want to measure the total effect, focus on controlling for confounders, not mediators.

Random variability

Random variability (or sampling variability) is the uncertainty that arises because we estimate population parameters using sample data. This is distinct from the sources of systematic bias (confounding, selection, measurement) which are issues of identification.

Statistical consistency

We can think of an estimator as a rule that takes sample data and produces a value for the parameter of interest in the population (the estimand). For example, we calculate the point estimate \(\hat{P}(Y=1 \mid A=a)\) for the population value \(P(Y=1 \mid A=a)\). Estimates will vary around the population value, but an estimator is considered consistent if the estimates get closer to the estimand as the sample size increases. We therefore have greater confidence in an estimate from a larger sample, which is reflected in a smaller confidence interval around it. Note, “consistency” here is a statistical property and different to the identifiability condition which uses “consistency” to mean a well-defined intervention.

Bringing this back to our cake example from earlier: imagine many bakers all trying to bake a cake using the same recipe (estimator). Each baker uses slightly different ingredients or ovens, so their cakes (estimates) vary. However, if you take the average cake quality across many bakers (many samples), that average gets closer to the perfect cake in the cookbook photo (the estimand) as the number of bakers increases. Consistency means that the recipe works on average, with many bakers the results converge to that ideal everyone is aiming for.

To contrast this with bias, now imagine the recipe (estimator) consistently calls for the wrong amount of sugar (i.e. model misspecification). No matter how many bakers try it, their cakes will systematically differ from the perfect cake in the cookbook (the estimand). This persistent deviation is bias, it shifts the average cake away from the target, unlike random variation which only increases the spread (variance) around the true cake. In other words, bias affects the center of the distribution of estimates, while random variability affects its width.

Random variability in experiments

The above is also true in experiments. Random assignment of the treatment doesn’t gaurantee exchangeability in the sample, but rather it means any non-exchangeability is due to random variation and not systematic bias. Sometimes you’re very unlucky and approximate exchangeability doesn’t hold (e.g. you find a significant difference in one or more pre-treatment variables that are confounders).

There’s ongoing debate about whether to adjust for chance imbalances in randomised experiments, particularly for pre-treatment variables that were not part of the randomisation procedure. The basic conditionality principle tells us we can estimate ATE without adjusting for covariates because treatment is randomised (unconfounded), but the extended version justifies conditioning on any pre-treatment X that are not randomised to improve precision (by explaining outcome variance), and estimate sub-group effects (heterogeneity). In practice, a pragmatic approach to avoid aver-adjustment is to adjust only for strong predictors of the outcome that are imbalanced enough to plausibly affect inference.

Confidence intervals

Most methods use standard formulas to calculate standard errors and confidence intervals. In some cases, multiple layers of uncertainty require more advanced techniques, such as bootstrapping, to fully capture all sources of random variability. However, confidence intervals only reflect uncertainty due to random variation; they do not account for systematic biases, whose uncertainty does not diminish as sample size increases.

Summary

Causal inference from observational data relies on strong assumptions to compensate for the lack of randomisation. Identification typically requires three core conditions: consistency (well-defined treatments lead to well-defined outcomes), exchangeability (no unmeasured confounding given observed covariates), and positivity (non-zero probability of treatment across covariate strata). Exchangeability is often the hardest to justify in real-world industry settings. The target trial framework and causal graphs (DAGs) help structure, assess, and communicate these assumptions, as well as the reasoning behind potential sources of bias. Visualising the relationships helps to distinguish what are the mediators, confounders, and colliders, ensuring bias is not introduced when conditioning (or not) on these variables. However, real world graphs can be complex, requiring careful consideration and expert knowledge. In general, you want to avoid over-adjusting, and focus on controlling for confounders.

Data Preparation

Returning to the target trial framework, one of its benefits is that it provides a clear blueprint for data preparation. It forces you to explicitly define: the outcome, target population (eligibility criteria), exposure definition, assignment process, follow up time period, and analysis plan. This helps clarify what data is needed and how it should be processed. In practice, getting to a clean analysis dataset often involves merging multiple sources, engineering features, and resolving issues like time alignment, units, or granularity. Therefore, during this stage, it’s important to run exploratory checks to catch potential problems early, such as:

Measurement error in key variables: Mislabeling treatments or misrecording outcome timestamps can significantly bias results. For example, if some users were marked as having received a notification but never actually did, the estimated treatment effect will be diluted. Similarly, if outcome events are logged with inconsistent timezones or delays (e.g. due to batch jobs), you might misalign treatment and outcome windows. Carefully validating treatment flags and verifying outcome timing logic (especially relative to exposure), can prevent subtle but critical biases.

Missing data: Missingness is rarely random in real-world data. For instance, users who churn stop generating events, resulting in censored outcomes. Or, income data might be missing more often for higher-earning users who opt out of surveys. If the probability of missingness is related to the treatment, outcome, or covariates, ignoring it can introduce bias. It’s important to diagnose the missingness pattern (e.g. checking the proportion missing by variable, treatment and outcome), and consider appropriate handling strategies, such as imputation, modeling dropout, or sensitivity analyses.

This is also a good point to evaluate the identifiability assumptions:

-

Consistency: Are you treating all individuals assigned to the same treatment identically? If there are multiple versions of the “same” treatment (e.g. different types of discounts), this assumption may be violated.

-

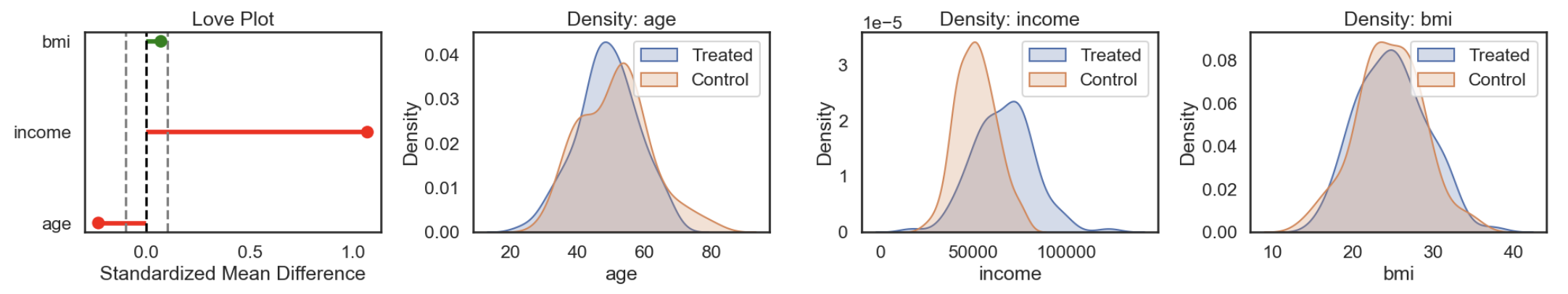

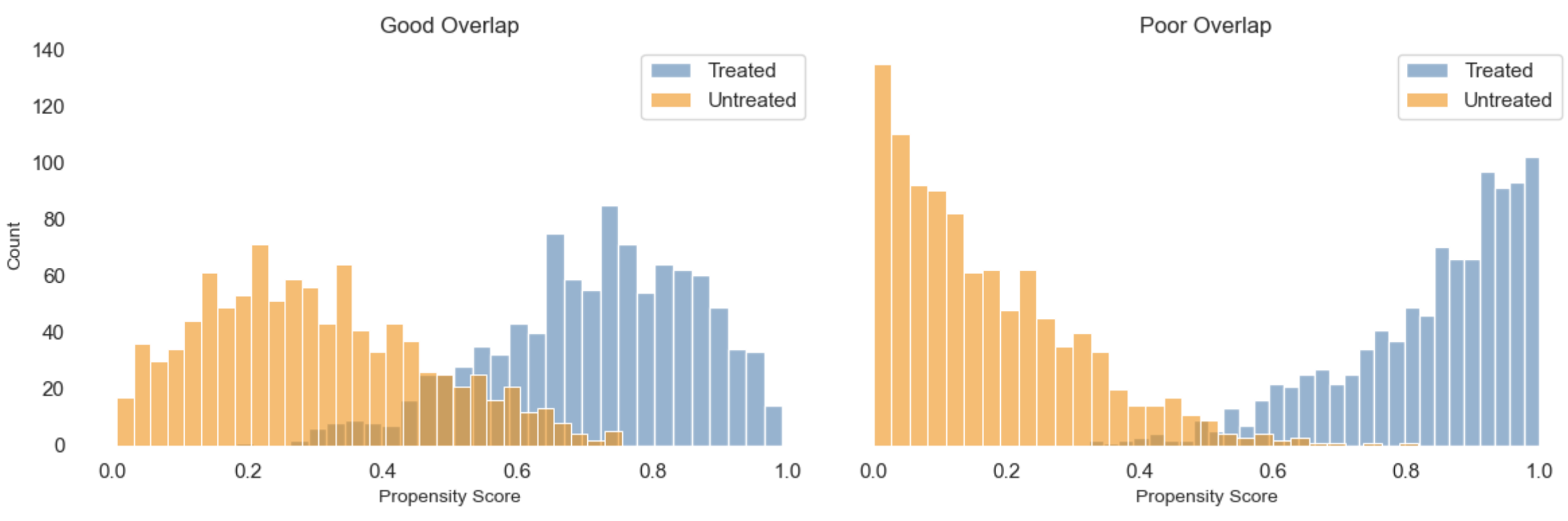

Positivity: For every combination of covariates, is there sufficient variation in treatment assignment? In other words, does every subgroup in your data have at least some treated and untreated units? This can be assessed by checking covariate distributions across treatment groups and identifying any zero-probability strata.

-

Exchangeability: This is more difficult to assess directly. It requires that, conditional on observed covariates, treatment assignment is as good as random. We’ll return to this later, as there are method specific diagnostics.

Estimating causal effects with models

So far, we’ve focused on identification: understanding when causal effects can be recovered from observational data under certain assumptions. We now turn to estimation: how to use models to compute those effects in practice. While this section emphasises observational data, the same tools can be applied to randomised experiments (for example, to improve precision by adjusting for covariates).

What is a model?

A model describes the expected relationship between treatment, outcome, and covariates. It defines the conditional distribution of the outcome given these inputs, either through a specified functional form or a flexible algorithm learned from data. In causal inference, models are used to estimate potential outcomes and causal effects under assumptions about the data-generating process.

Many commonly used models are parametric, meaning they assume a fixed functional form. For example, a linear model assumes the expected outcome increases at a constant rate with treatment:

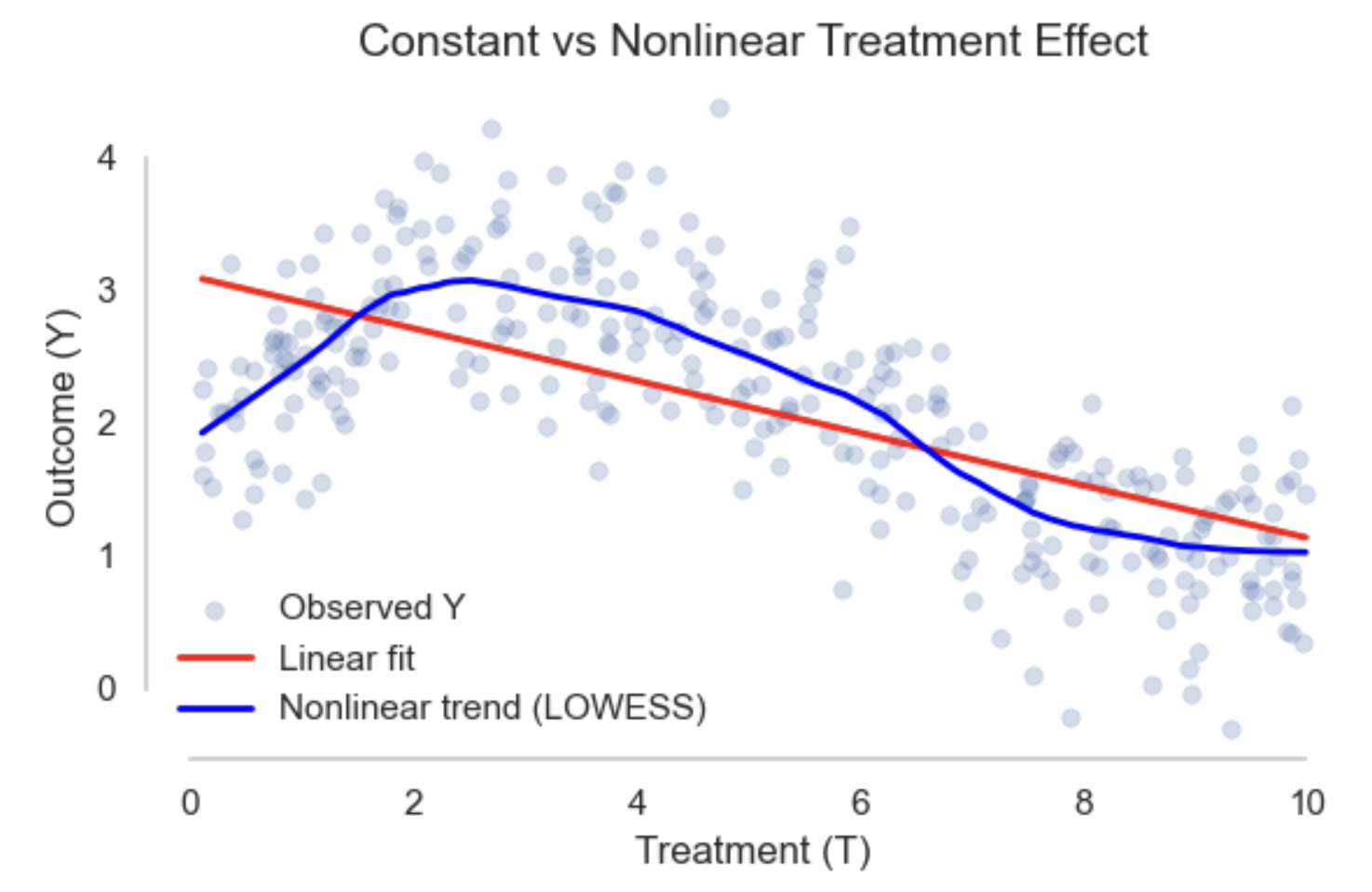

\[E[Y \mid T] = \theta_0 + \theta_1 T\]This is useful when treatment is continuous and the number of observed treatment levels is large or infinite, since the model summarises the effect using only a few parameters. However, to make this work, it must impose strong assumptions like linearity.

In contrast, nonparametric models make fewer assumptions and allow the data to determine the shape of the relationship. Returning to the linear model above, it also serves as a saturated model when treatment \(T\) is binary. In this case, the model estimates two conditional means (one for each treatment group), with no further assumptions. Although written in a linear form, it imposes no constraints and fits the data exactly, making it nonparametric in this specific setting.

Why Models Are Needed

Even if identification assumptions are satisfied, causal effects often can’t be computed directly from raw data. Reasons include:

- High-dimensional covariates: Exact matching becomes infeasible.

- Continuous treatments: Not all treatment levels are observed.

- Sampling variability: Finite data leads to noisy or unstable estimates.

Models help address these challenges. They allow adjustment for covariates (supporting exchangeability), interpolation across treatment levels (helping with positivity), and estimation of potential outcomes under alternative treatment scenarios (relying on consistency). Models can also stabilise estimates by pooling information across similar observations. In this way, modeling isn’t just about computation, it’s how the identifying assumptions are operationalised in practice.

Prediction vs. Inference

Models, by default, describe statistical associations in the observed data; they are not inherently causal. As covered in the introduction to this guide, it’s important to distinguish between using models for prediction (\(E[Y \mid T, X]\)) and for causal inference (\(E[Y(t)]\)). A model may suggest that customers who received a discount spent more, but this observed correlation does not prove the discount caused the increase. Similarly, if you predict bookings based on hotel price without controlling for seasonality, you might incorrectly think increasing the price causes increased demand. In other words, accurately forecasting outcomes does not guarantee valid causal effect estimates.

While predictive models can be evaluated using performance metrics on held-out data, causal inference depends on careful study design and justified assumptions. Specifically, the three identifiability conditions must be met: exchangeability, positivity, and consistency. In addition to these causal assumptions, model-specific assumptions must also hold. For parametric models, these include:

- No measurement error, especially in confounders (an assumption often overlooked but critical for validity); and,

- Correct functional form, meaning the model accurately reflects the underlying data-generating process (no misspecification).

Since all models simplify reality, some degree of misspecification is inevitable. This makes sensitivity analysis essential for assessing how results change under alternative settings. Transparency about assumptions and rigor in testing their robustness help build confidence in the resulting causal estimates.

Extrapolation

A risk with models like regression is it introduces the possibility of extrapolation. Interpolation refers to estimating outcomes within the range of observed data and is generally safe. Extrapolation occurs when making predictions outside the support of the data. For example, estimating effects for treatment levels or covariate profiles that are rare or unobserved. This relies entirely on model assumptions and can lead to misleading results. In causal inference, extrapolation should be avoided unless supported by strong domain knowledge.

Common ATE models

The following sections will go through some of the common models used to estimate the ATE, including:

1. Adjustment-Based Methods: These rely on adjusting for observed confounders to identify causal effects.

- Outcome regression (GLMs): Estimate the expected outcome given treatment and covariates using models such as linear or logistic regression.

- G-computation (standardisation / g-formula): Estimate causal effects by modeling the full outcome distribution under each treatment regime. These are especially useful for longitudinal or time-varying treatments.

- Matching methods: Compare treated and untreated units with similar covariates or scores to mimic a randomised experiment.

- Propensity score methods: Balance covariates between treated and untreated groups before estimating effects.

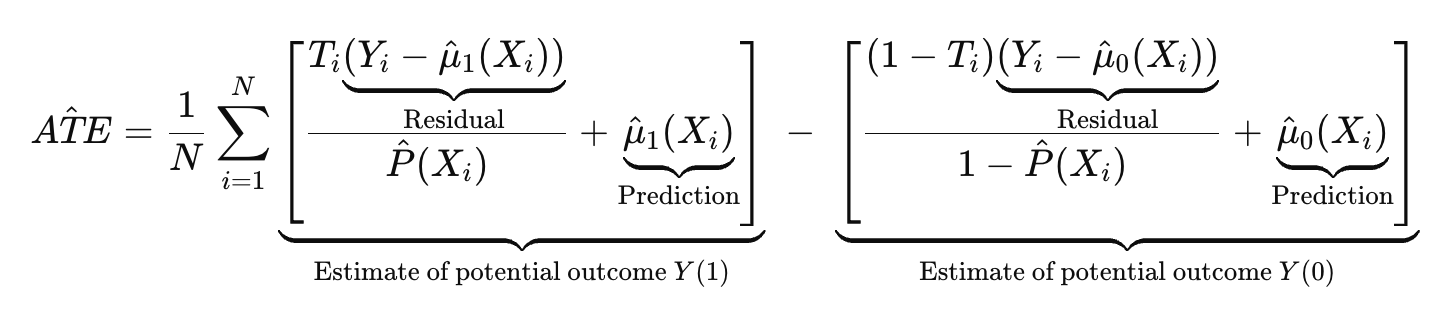

- Orthogonal machine learning (Orthogonal ML): Combine machine learning with causal assumptions to reduce bias and improve robustness.

2. Quasi-Experimental Designs: These exploit natural experiments or design features to identify causal effects without relying solely on observed confounding adjustment.

- Instrumental Variable (IV) analysis: Uses external variation that influences treatment but not directly the outcome to handle unmeasured confounding.

- Difference-in-Differences (DiD): Compares changes over time between treated and control groups in panel data.

- Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE): A panel data regression approach extending DiD with multiple groups and time periods.

- Synthetic Control Methods: Construct a weighted combination of control units to approximate the treated unit’s counterfactual.

- Bayesian Structural Time Series (BSTS): A Bayesian approach to estimate causal impacts in time series, often used in policy evaluation.

- Regression Discontinuity Designs (RDD): Leverages treatment assignment cutoffs to estimate local causal effects near the threshold.

Each of these methods builds on the core identification assumptions but uses different strategies to estimate causal effects, depending on the data structure, assumptions, and sources of bias. There is no one size fits all approach, as most methods are designed for a narrow set of conditions. Therefore, it’s useful to be familiar with a range of approaches, and go deeper in those most relevant to your use case.

Adjustment based methods

Outcome regression

Generalised Linear Models (GLMs) such as linear regression are a popular choice for estimating ATE when there isn’t complex longitudinal data. For example, using a binary variable to indicate whether an observation was treated or not (T), for a continuous outcome we get:

\[Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T_i + \epsilon_i\]Where:

- \(\beta_0\) is the average Y when \(T_i=0\) (i.e \(E[Y \mid T=0]\))

- \(\beta_0 + \beta_1\) is the average Y when \(T_i=1\) (i.e. \(E[Y \mid T=1]\))

- \(\beta_1\) is therefore the difference in means (i.e. \(E[Y \mid T=1] - E[Y \mid T=0]\))

- \(\epsilon\) is the error (everything else that influences Y)

In this single variable case, the linear regression is computing the difference in group means. If T is randomly assigned then \(\beta_1\) unbiasedly estimates the ATE:

\[ATE = \beta_1 = \frac{Cov(Y_i, T_i)}{Var(T_i)}\]However, when using observational data, the key assumption of exchangeability often fails (\(E[Y_0 \mid T=0] \neq E[Y_0 \mid T=1]\)). To address this, we can extend the model to control for all confounders \(X_k\) (i.e. variables that affect both treatment and outcome):

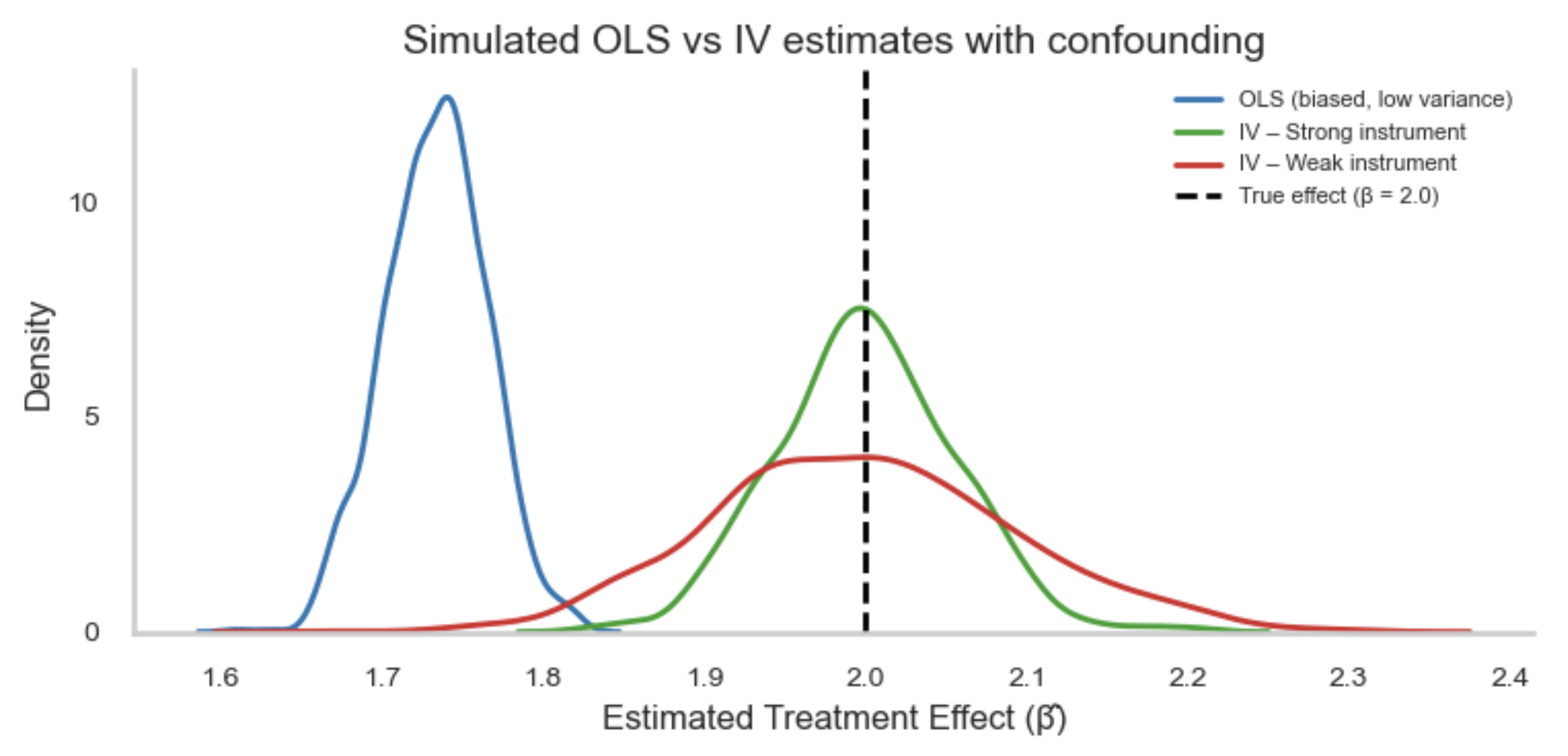

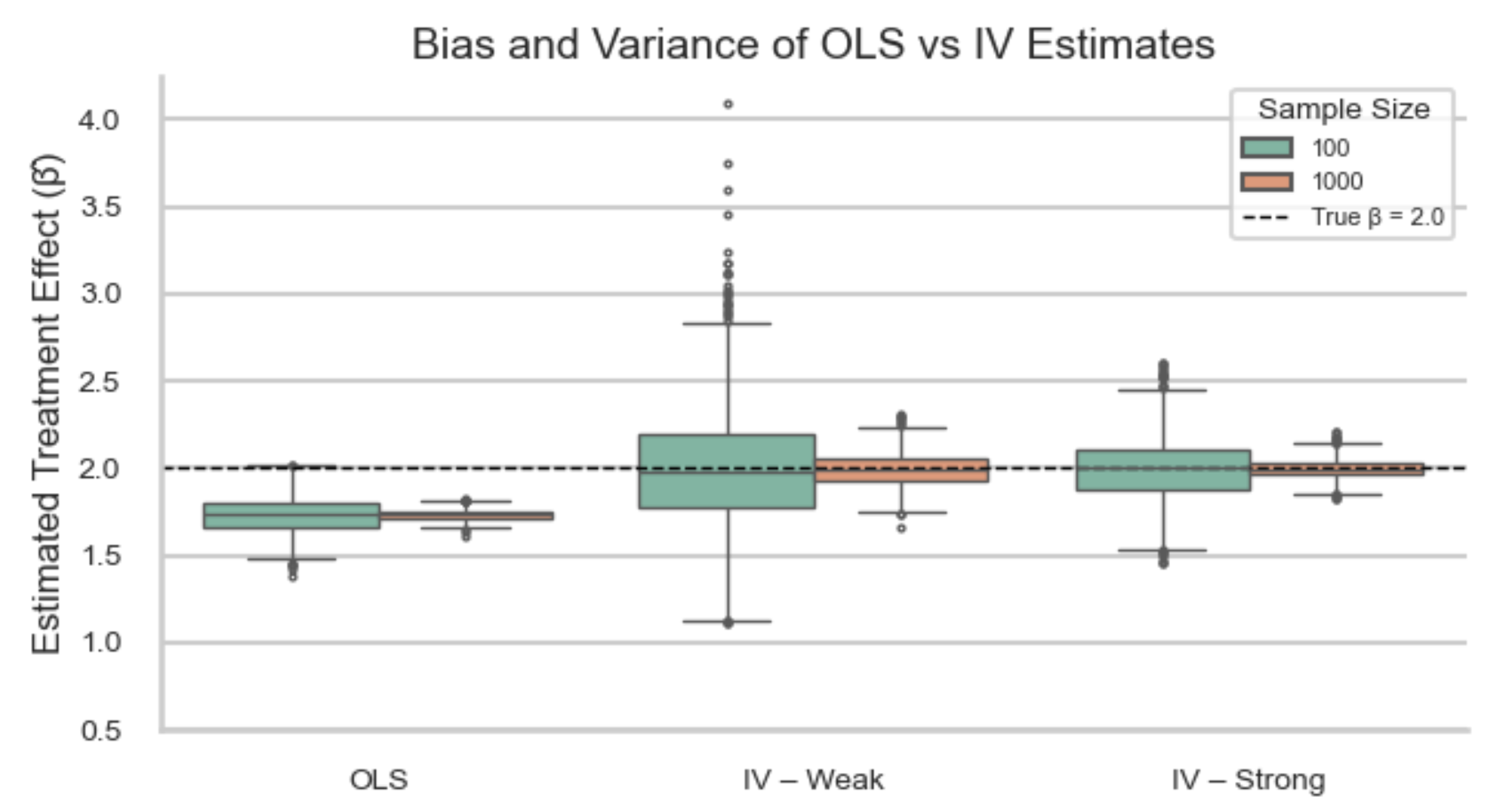

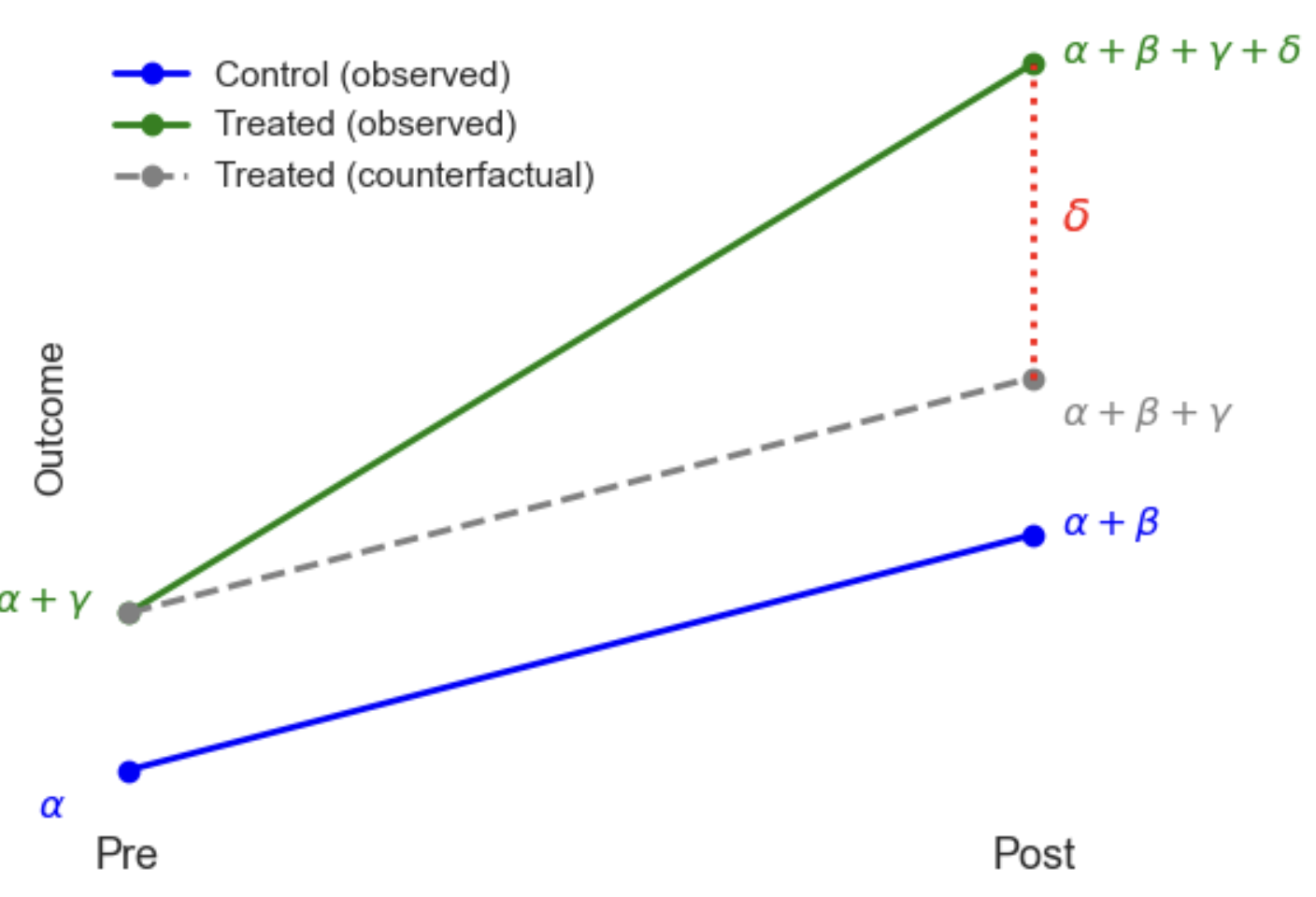

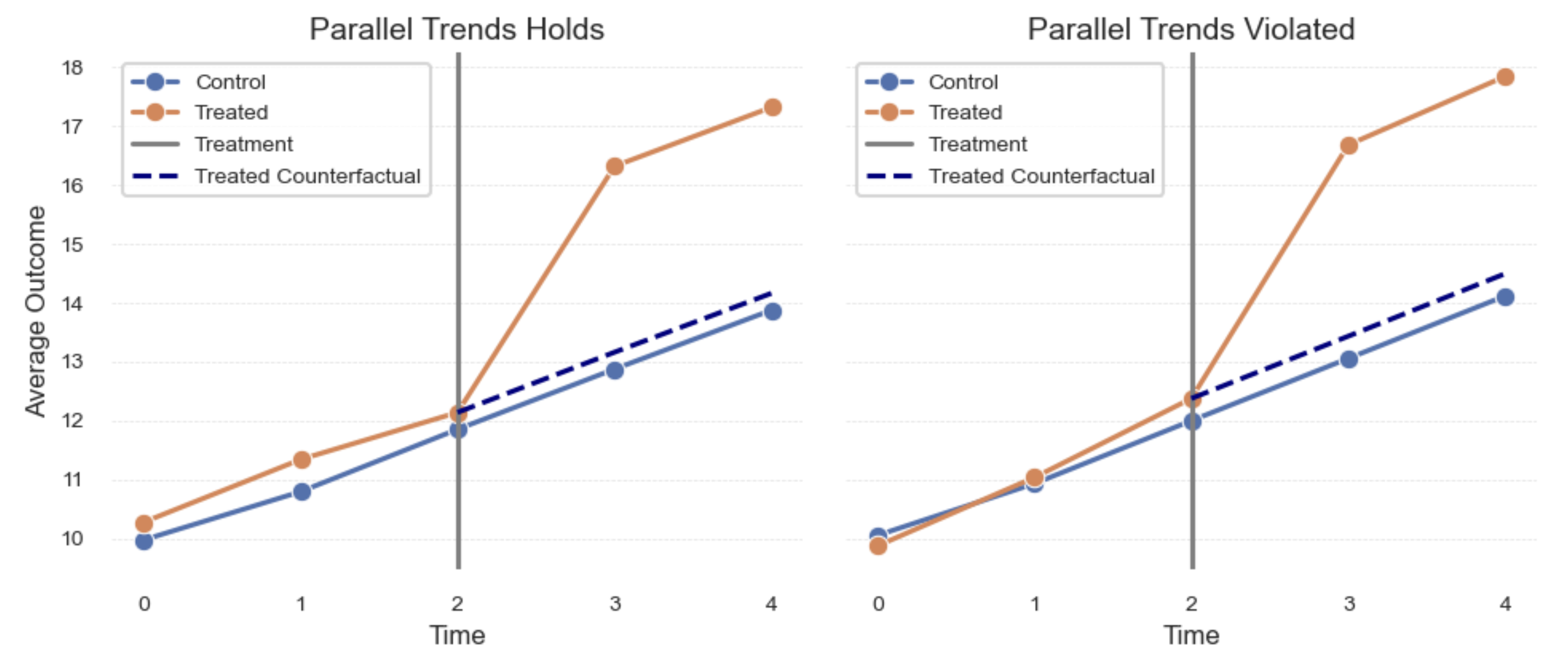

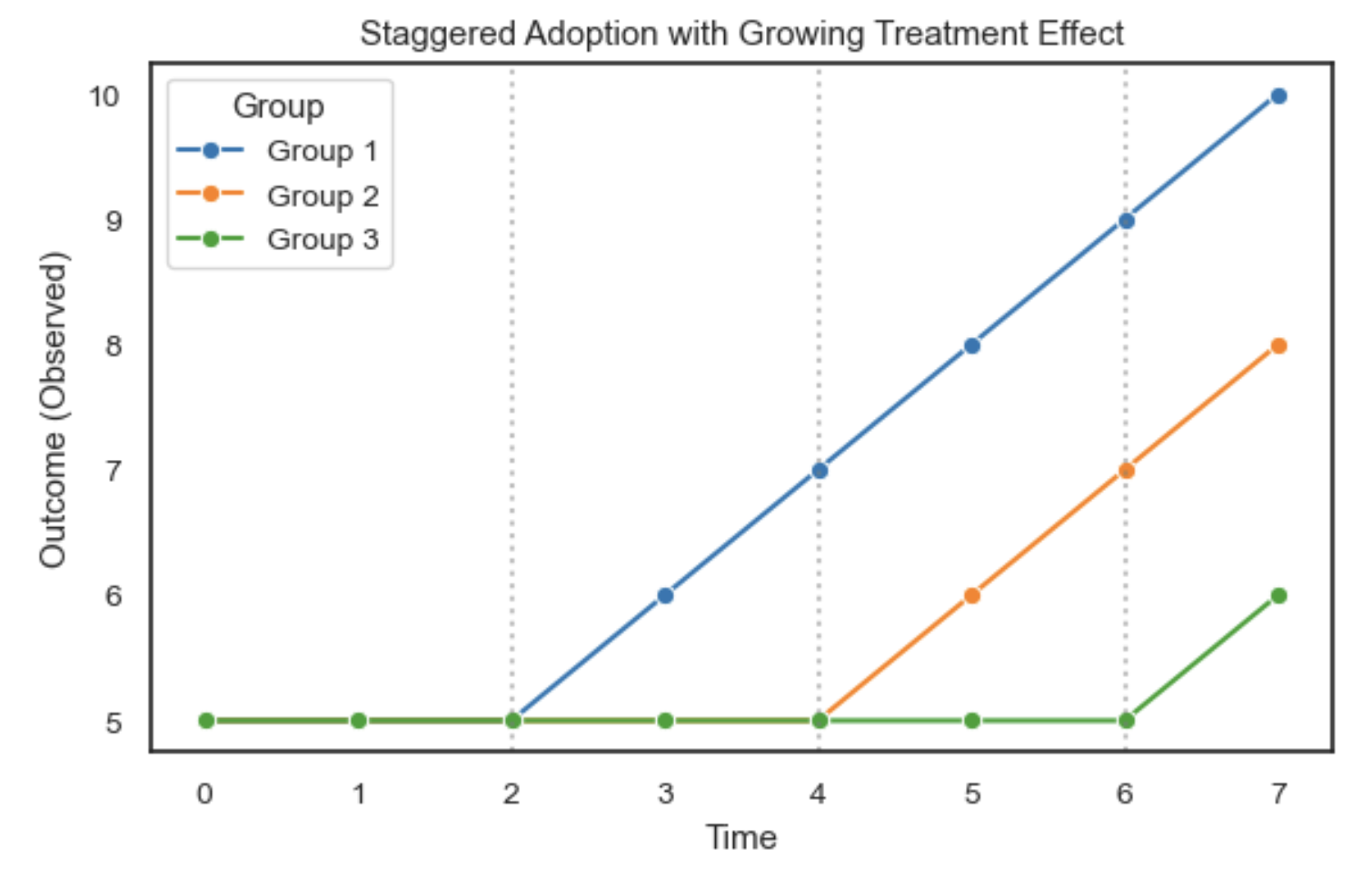

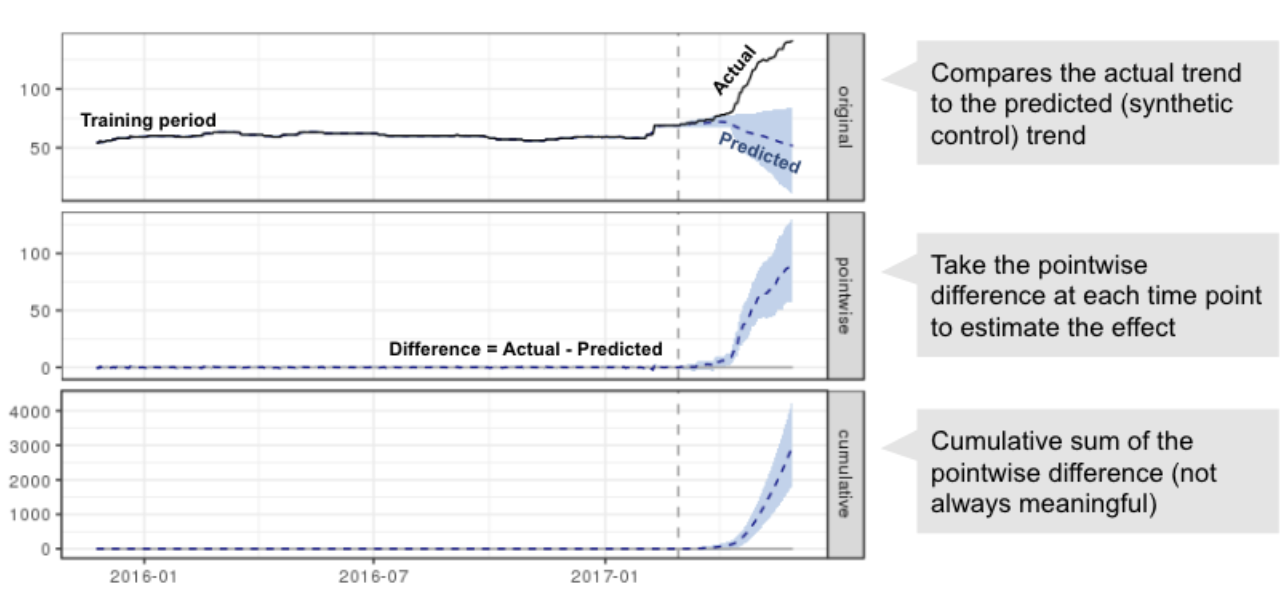

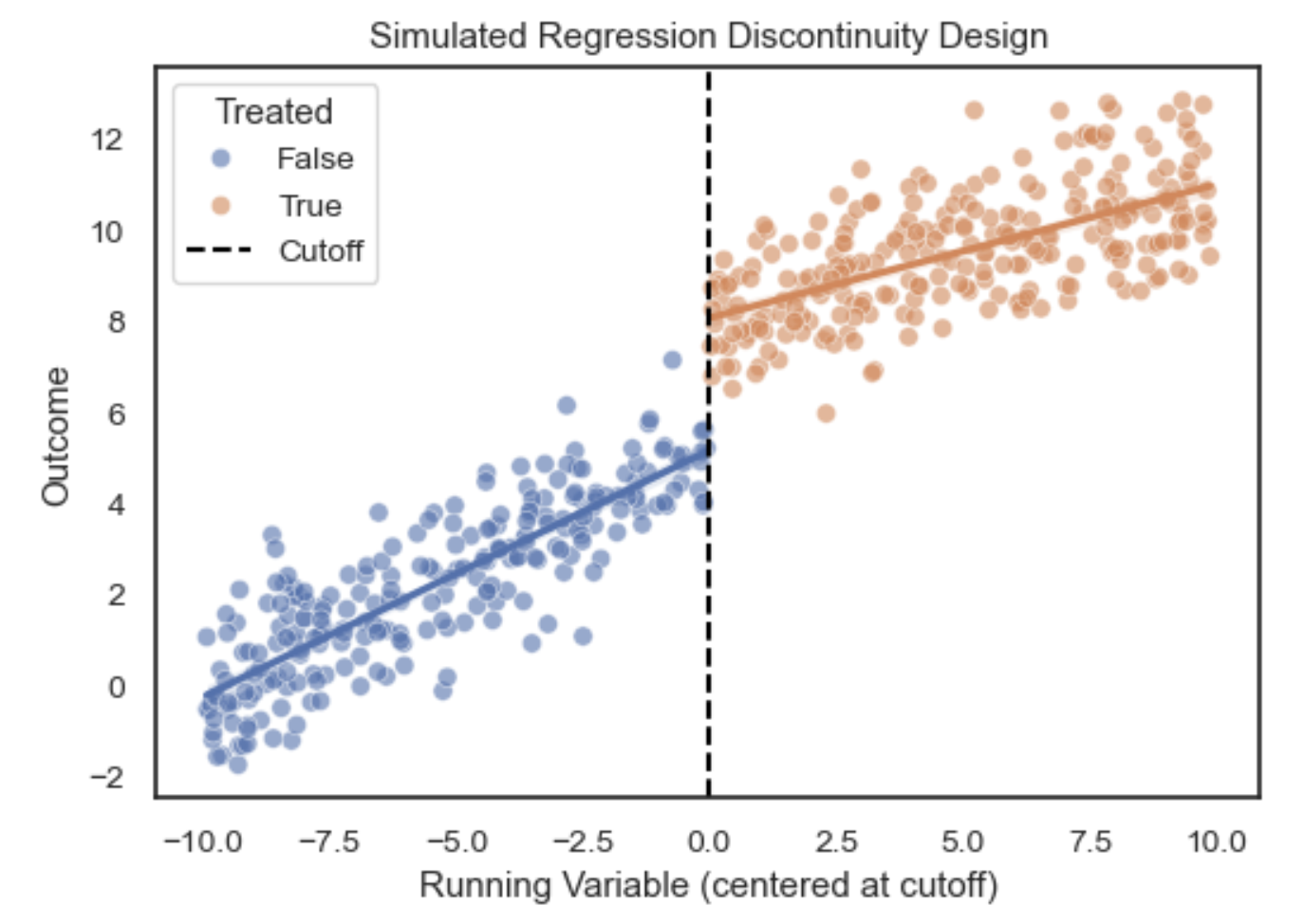

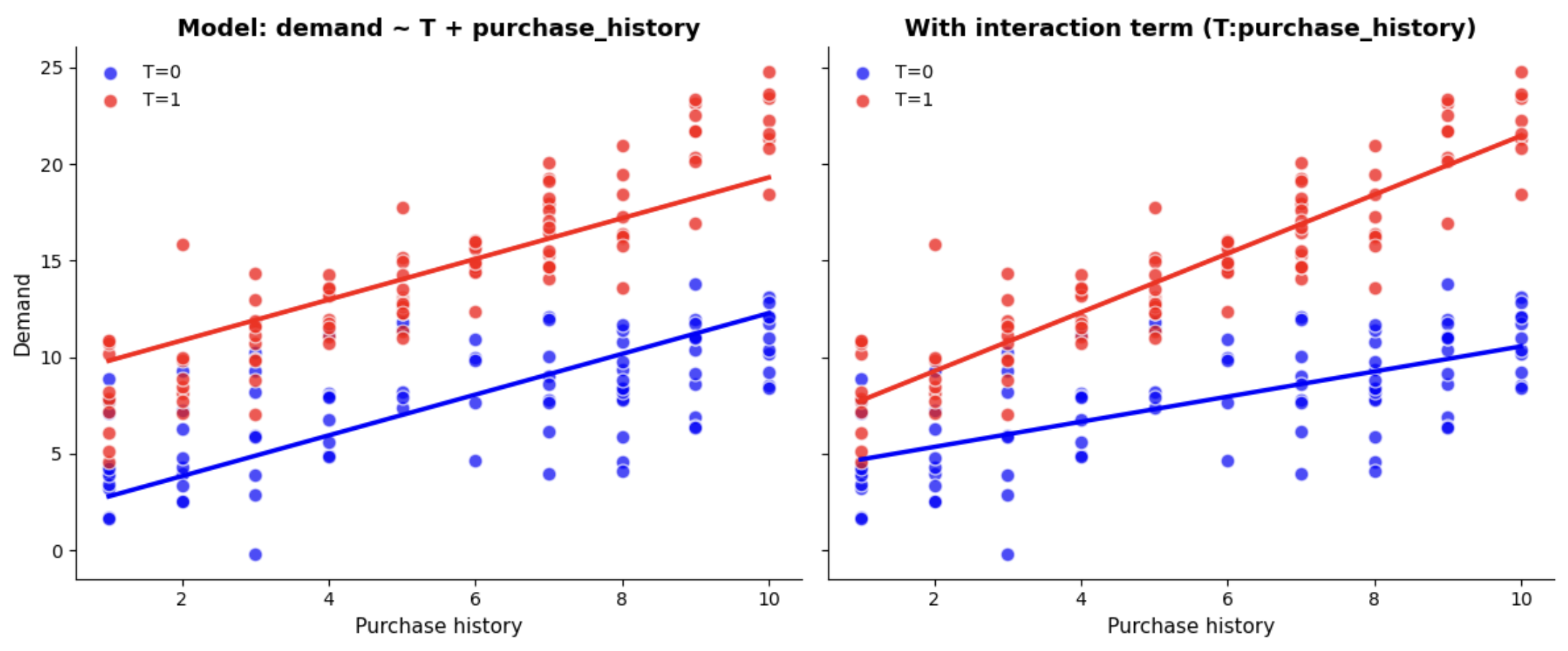

\[Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 T_i + \beta_k X_{ki} + \epsilon_i\]Now \(\beta_1\) estimates the average treatment effect (difference in group means), conditional on the confounders (i.e. the conditional difference in means). Under linearity and correct model specification, this equals the marginal ATE (population-average ATE).