Non-inferiority testing

Non-inferiority tests are just one-sided tests with a margin, but they are quite useful in experimentation. For example, let’s say you’re adding a new feature to your web shop. You’re primarily interested in increasing revenue, but at the same time you don’t want to hurt other metrics like the average page load time, or volume of customer service queries. Metrics that you just want to keep an eye on like these are sometimes called ‘guardrails’. For these metrics, we want to make sure the new version of the site is not worse (non-inferior) to the current, so we only need to test for changes in one direction.

Hypothesis

Like with all hypothesis tests, it’s impossible to prove there is no effect. Instead, we test whether the difference is not worse than some meaningful acceptable threshold. For example, we may be ok with some increase in customer service volumes (particularly if it may be temporary), but decide anything above 5% is too high a cost. In this case 5% will be our threshold, and we’ll test whether the change exceeds this or not.

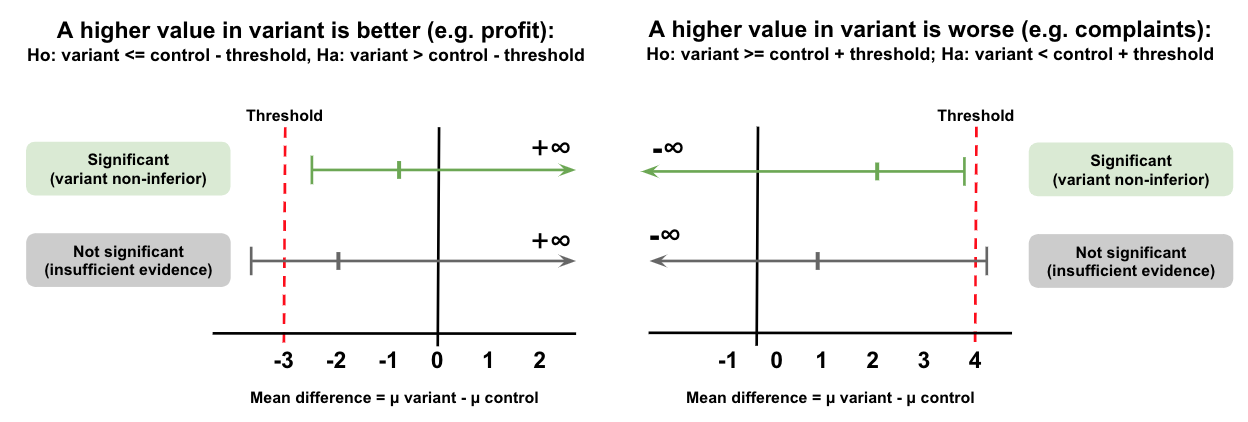

Depending on the direction of ‘good’, this gives us the following hypotheses (using a t-test on two independent samples as an example):

If high values are good: (e.g. revenue or number of purchases per visitor)

In this case rejecting the null hypothesis implies that the variant mean is greater than the control mean minus the threshold. In other words, we allow some margin for the variant (group 2) to be worse than the control (group 1). As long as the difference is above the threshold, we conclude it’s non-inferior:

- Ho: mean2-mean1 <= threshold OR equivelantly mean 2 <= mean1 - threshold

- Ha: mean2-mean1 > threshold OR equivelantly mean 2 > mean1 - threshold (non-inferior)

If high values are bad: (e.g. average page load time or customer service tickets)

In this case, rejecting the null hypothesis implies the variant mean (group 2) is less than the control mean (group 1) plus the threshold. Again, we allow some negative impact by adding the threshold on top of the control mean.

- Ho: mean2-mean1 >= threshold OR equivelantly mean2 >= mean1+threshold

- Ha: mean2-mean1 < threshold OR equivelantly mean2 < mean1+threshold (non-inferior)

Note, here we’re using one-sided confidence intervals (as we’re only testing for a difference in one direction).

Python function:

Note, the statistical tests remain the same (one-sided ttest in this case). We simply shift the base mean to allow some gap (subtracting/adding the threshold) in order to change the null hypothesis.

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind_from_stats

import numpy as np

def non_inferiority_ttest(mean1, stddev1, n1, mean2, stddev2, n2, relative_difference, equal_variance=False, increase_good=True):

'''

Perform a one-sided t-test with a non-inferiority threshold for two independent samples.

mean1/2: group mean

stddev1/2: standard deviation of each group

n1/2: number of observations in each group

relative_difference: threshold as a percentage of the base group (e.g. 0.1=10% difference)

equal_variance: if False, uses Welch's t-test.

increase_good: if True, Ho: mean2 <= mean1 - threshold. Else Ho: mean2 >= mean1 + threshold.

Returns:

'''

delta = relative_difference * mean1

if increase_good:

threshold = mean1 - delta

else:

threshold = mean1 + delta

tstat, pval = ttest_ind_from_stats(mean1=threshold,

std1=stddev1,

nobs1=n1,

mean2=mean2,

std2=stddev2,

nobs2=n2,

equal_var=equal_variance)

if increase_good:

pvalue = pval/2.0

else:

pvalue = 1 - pval/2.0

return tstat, pvalue

Example: Increase is good, threshold is 0.1 (10%).

Ho: mean2 >= mean1 - mean1*0.1

np.random.seed(26)

group1 = np.random.normal(47, 3, 100)

group2 = np.random.normal(42, 3.5, 105)

relative_difference_threshold = 0.1

mean_group1 = np.mean(group1)

mean_group2 = np.mean(group2)

stddev_group1 = np.std(group1, ddof=1)

stddev_group2 = np.std(group2, ddof=1)

tstat, pval = non_inferiority_ttest(mean1=mean_group1,

stddev1=stddev_group1,

n1=len(group1),

mean2=mean_group2,

stddev2=stddev_group2,

n2=len(group2),

relative_difference=0.1,

equal_variance=False,

increase_good=True)

print('One sided ttest: t value = {:.4f}, pval = {:.4f}'.format(tstat, pval))

One sided ttest: t value = 1.3677, pval = 0.0865

Notes

- It’s generally advisable to do a two-sided test. Only do a non-inferiority if you truly only care about differences in one direction (e.g. checking the change doesn’t ‘hurt’ key business metrics), and missing effects in the untested direction negligible.

- Keep in mind non-inferior does not mean equivelant or superior, and inconclusive does not mean inferior (it could be inferior as the CI overlaps with the margin, but also may not be).

- If you’re CI doesn’t overlap with zero, it might be tempting to interpret it as a two-sided test, concluding the effect is higher/lower in variant. However, this is incorrect. The one-sided confidence interval is only valid for the one-sided non-inferiority test (i.e. the CI of a two-sided test may or may not overlap with 0). Further, changing the hypothesis based on the result would also mean we lose the false positive rate and power gaurantees.

- If you’re bounds are really wide and the result is not conclusive (can’t rule out inferiority), the test was likely underpowered. You can rerun with a larger sample to get more confidence.

- If you’re not sure about the traffic size or baseline for your metric pre-experiment, you could run the experiment for a short period before doing the power calculation. However, do not use this to decide the margin (acceptable cost). Your margin should be based on the cost or value of the change, and the estimated difference is unlikely to be accurate anyway in such a short period (will fluctuate).

- Setting the margin based on the relative (% difference from group 1) is preferred as an absolute margin is reliant on the pre-experiment estimates being correct (reference).

- Over time, experiments with a small negative effect (within the margin) can accumulate, causing a much larger negative impact (cascading losses). This is an issue with all experiments, but of particular concern given we allow a margin.

- I’ve shown the non-inferiority approach for a t-test, but the concept works equally well for other metrics and tests (e.g. proportions, and mann-whitney test).