Confidence intervals

The confidence interval quantifies the uncertainty of a sample estimate. When we estimate a population parameter with a sample statistic, it’s unlikely it equals the population value exactly. For example, imagine we take a random sample of 10 birds out of thousands in a wildlife reserve each day, and compute their average weight. The sample averages will vary around the population average, but rarely equal it (as each time we get a slightly different sample by chance). Similarly, when we do an AB test, we randomly split the population into two groups (or a random percent of it). The observed difference between group A and B is an estimate of the true population difference (treatment effect), but the difference would vary if we repeated the experiment many times.

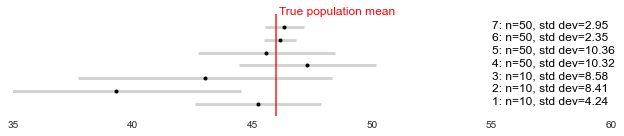

As the name suggests, the confidence interval gives us a range of values around the sample estimate, within which we’re reasonably confident the actual population parameter lies (in the first example, the average weight of all birds in the reserve). Below are some examples. As demonstrated, the larger the sample size, and the smaller the standard deviation in the metric (i.e. the spread of the values), the closer the sample estimates will be to the population value, and the narrower the confidence interval will be. Meaning we can be more certain about the likely population value.

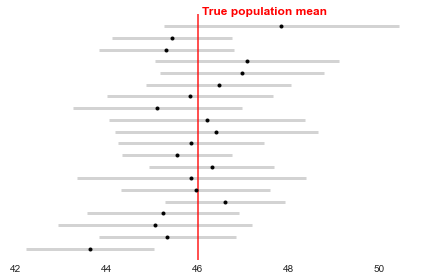

However, the population value will either be within the interval or not. The confidence level (1-alpha) determines how often we expect the interval to contain the population value, based on how much estimates would vary across repeated experiments. For example, with 95% confidence (alpha=0.05), 95% of the time (if we repeat the same sampling process), we get a confidence interval that contains the true value. In the other 5%, the true value is not in the CI at all (i.e. 1/20 experiments I’m wrong and return a CI that doesn’t contain the true value). This is demonstrated below, with the interval closest to the x-axis not containing the population mean.

The higher the confidence required, the wider the confidence interval will be to increase the chances of capturing the population value.

Technical details

Hopefully you have some intuition now on what the confidence interval means. So how do we calculate this magical interval, ensuring it includes the population value x% of the time?

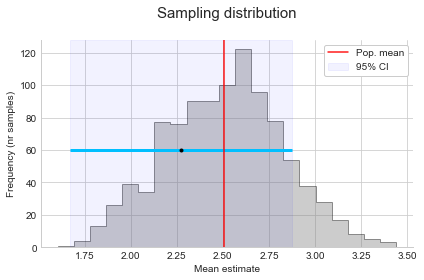

The sampling distribution:

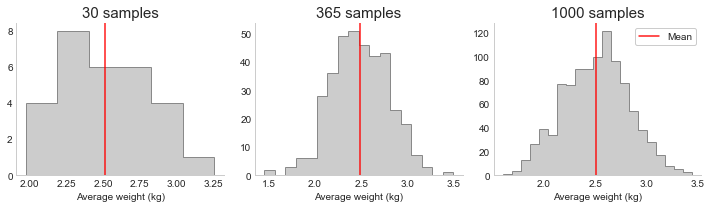

Coming back to our example of taking the average weight of 10 birds per day from thousands in a reserve. If we plot the resulting estimates for the average weight in a histogram, we have what is called the sampling distribution (see below). Sometimes we will by chance get a high estimate, other times a low estimate. However, the more samples we take, the more this distribution will converge to a normal (bell shaped) distribution, centered on the population value. This is what the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) tells us: as n increases, the distribution converges to the normal distribution (with the same mean as the population, but a smaller variance).

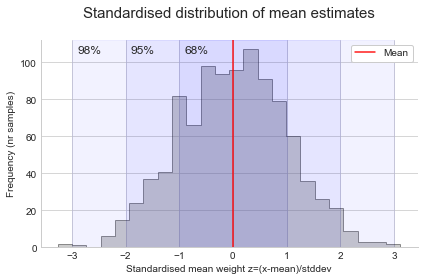

This means that as long as our sample size is large enough, and the observations are independent (the weight of a bird is not influenced by the weight of the other birds), we can just use a normal distribution to estimate the sampling distribution. We don’t need to actually repeat the sampling many times. More specifically, we use a standard normal curve to make comparisons easier. This just standardises values to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 by taking the difference between each x value and the mean, and dividing by the standard deviation:

\[Z = \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma}\]Plotting the values of Z (standard normal curve), we can easily see the 68-95-98 rule: 68% is within 1 standard deviation of the mean, 95% is within 2 standard deviation of the mean, and 99.7% is within 3 standard deviation of the mean. This means we expect 68% of our samples to produce a mean estimate that’s within 1 standard deviation of the population mean, and so on.

From the sampling distribution to a confidence interval:

The confidence interval is actually just a summary of the sampling distribution. First, we need the standard error:

- 1) The standard error: How far off on average we expect a sample estimate to be from the population mean. As n increases, the standard error decreases. Not to be confused with standard deviation (variability in a measured quantity). Note, for the calculation below, the population standard deviation ($\sigma$) is not usually known, so it’s usually estimated with the sample standard deviation (s).

- 2) The confidence interval (CI): The sampling distribution tells us the proportion of values within x standard deviations. E.g. for a 95% two-sided confidence interval, 95% of the sample estimates will fall between the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile (alpha=5%, split either side). Which is equivelant to z=1.96 (standard deviations from the mean). Therefore, we just need to calculate the standard deviation for the sampling distribution (standard error), and take x multiples depending on how much coverage of the samples we want. Placing this resulting distance around each sample estimate in the distribution, this gauarantees the interval will include the population value (the center), for x% of the sample estimates (95% in the case of z=1.96).

Where ‘s’ is the sample standard deviation, and the critical value ‘z’ is based on our selected confidence. E.g. z=1.96 for 95% confidence. A reminder, the z value comes from looking at the standardised sampling distribution and calculating how many standard deviations do we need to have the area under the curve cover 95% of values.

Summary

Hopefully, you can see now that we’re just taking the distance from the population mean (estimated by the mean of the sampling distribution), to the point at which we capture x% of the sample estimates. So reversing that thinking, this means if I now put that distance around each of my sample estimates, x% of the time it will overlap with the population mean. Hence, with a 95% confidence interval, there’s a 19/20 chance a randomly chosen interval overlaps with the mean.

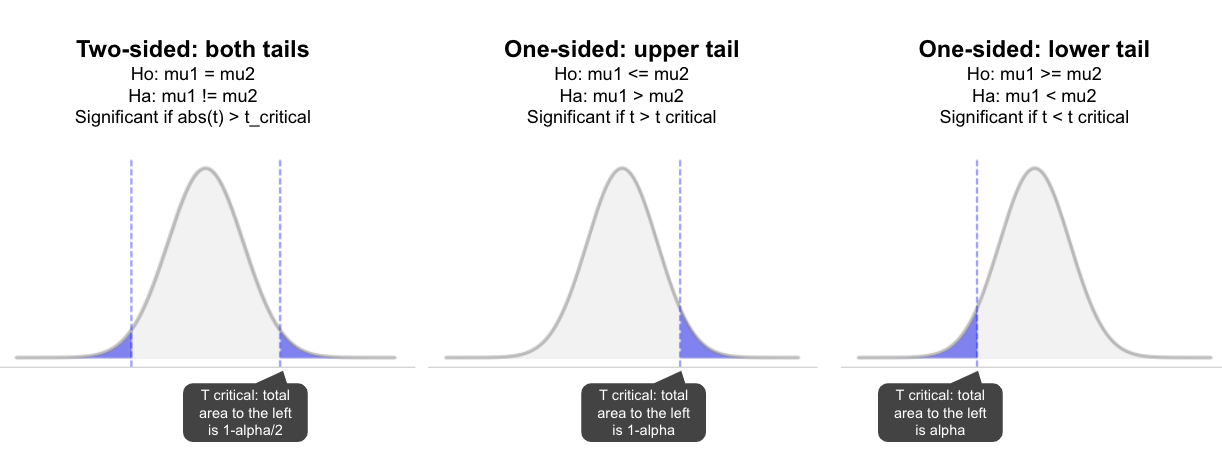

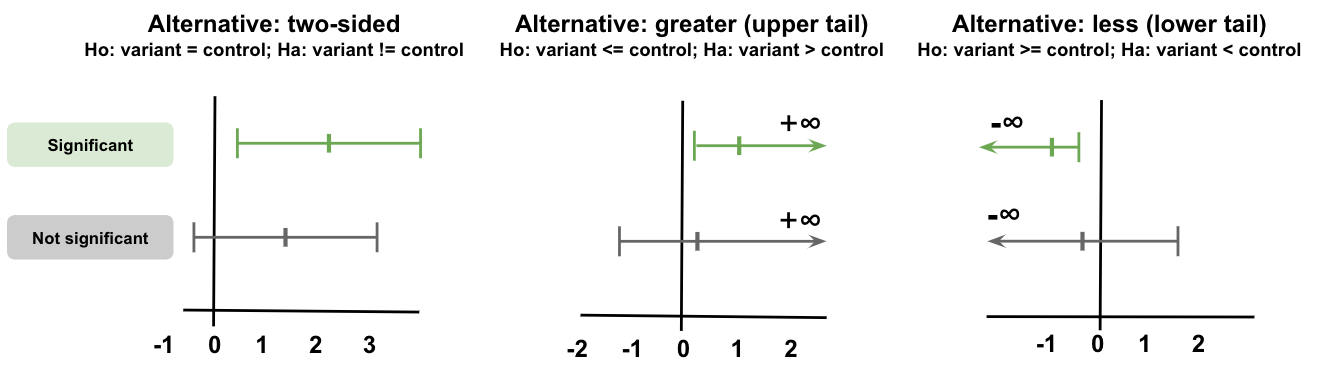

One vs two sided tests

A two sided test checks both tails to assess the null hypothesis that the observed value differs to the hypothesised (e.g. mu 1 != mu 2). Whereas, in a one-sided test we state upfront the expected direction of the difference and only look in that direction (one tail). This means that with the same settings:

- The one-tail p-value will be half the two-tail; and,

- The two-tail p-value is twice the one-tail (assuming the predicted direction is correct).

Similarly, for the confidence interval, the two-sided test will give bounds on both sides of the estimate. In contrast, as we’re only interested in one direction, we only estimate one-side of the confidence interval (with the other side going to infinity).

Calculations

We have mostly worked with the example of estimating a population mean from one sample. Next we will walk through the confidence interval for different statistics, and also for differences between two samples (e.g. for AB experiments).

Confidence interval for one sample estimates:

The below tests all assume the values are independent (don’t influence each other) and randomly selected, and the estimate comes from a normal distribution. At the end I’ll discuss some options for non-normal distributions.

Mean (using t distribution)

In general the t-distribution is recommended over the z-distribution because it can handle both small and large sample sizes (it will converge to z, a normal distribution, as n increases).

\[CI_\text{mean} = \bar{x} \pm t_c \frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}\]import numpy as np

import scipy.stats as st

np.random.seed(26)

sample = np.random.normal(46, 3, 10)

sample_mean = np.mean(sample)

sample_stddev = np.std(sample, ddof=1)

n = len(sample)

alpha = 0.05

conf = 1 - (alpha / 2)

critical_val = st.t.ppf(conf, (n-1))

se = sample_stddev/(n**0.5)

ci_lower, ci_upper = sample_mean-(critical_val*se), sample_mean+(critical_val*se)

print('95% CI = ({:.2f}, {:.2f})'.format(ci_lower, ci_upper))

st_se = st.sem(sample)

st_ci_lower, st_ci_upper = st.t.interval(alpha=1-alpha,

loc=sample_mean,

scale=st_se,

df=n-1

)

print('95% CI with scipy = ({:.2f}, {:.2f})'.format(st_ci_lower, st_ci_upper))

95% CI = (43.23, 47.40)

95% CI with scipy = (43.23, 47.40)

Proportion (using normal approximation)

One of the other common statistics we want to estimate for a population is a proportion (e.g. conversion rate). If the sample is large enough (np and n(1-p) are greater than 5), we can estimate a population proportion using the normal approximation:

\[SE_\text{p} = \sqrt\frac{\hat{p}(1-\hat{p})}{n}\] \[CI_\text{p} = \hat{p} \pm z*SE_\text{p}\]import numpy as np

import scipy.stats as st

from statsmodels.stats.proportion import proportion_confint

sample = [1,0,1,1,0,0,0,0]

sample_p = np.mean(sample)

n = len(sample)

alpha = 0.05

conf = 1 - (alpha / 2)

critical_val = st.norm.ppf(conf)

se = np.sqrt(sample_p*(1-sample_p)/n)

ci_lower, ci_upper = sample_p - critical_val*se, sample_p + critical_val*se

print('95% CI (using z) = ({:.2f}, {:.2f})'.format(ci_lower, ci_upper))

nr_successes = np.sum(sample)

nr_trials = len(sample)

alpha = 0.05

sm_ci_lower, sm_ci_upper = proportion_confint(count=nr_successes,

nobs=nr_trials,

alpha=alpha)

print('95% CI using statsmodels = ({:.2f}, {:.2f})'.format(sm_ci_lower, sm_ci_upper))

95% CI = (0.04, 0.71)

95% CI using statsmodels = (0.04, 0.71)

Variance

The confidence interval for the variance is not often used on it’s own, but comes up in the f-test (equality of variances of different populations). When the population is normally distributed, the sample means follow a normal distribution, and the sample variances follow a chi-square distribution. Note, the chi square distribution is asymptotic (approaches x but never touches it), and the shape depends on the degrees of freedom. With smaller samples it’s asymmetrical (not equal on either side), but as per the central limit theorem (CLT), it converges to a normal distribution as n increases.

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

sample_values = np.random.normal(46, 3, 10)

alpha = 0.05

n = len(sample_values)

sample_variance = np.var(sample_values, ddof=1)

dof = n - 1

ci_upper = (n - 1) * sample_variance / stats.chi2.ppf(alpha / 2, dof)

ci_lower = (n - 1) * sample_variance / stats.chi2.ppf(1 - alpha / 2, dof)

Confidence interval for difference between two independent samples:

Let’s say we run an AB experiment where we take a random sample of 100 injured birds and split them 50/50 into two groups. Group A gets the regular food (control), and group B gets a new version with added vitamins that we think will speed up their average recovery time (measured in days). Now we observe the birds for a month and at the end calculate the average recovery time in each group.

- Ho: muA = muB

- Ha: muA != muB

Difference in means

What is the difference in the average recovery time of group A and group B (muB-muA)? Assuming the observations are independent, and the distribution of the difference is normal (which we can validate with simulations), we can run a t-test and use the t distribution to compute a confidence interval around the difference estimate.

Using t-interval (assumes groups have equal variance)

\[t = \frac{\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2}}{s_p \sqrt{(\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2})}}\] \[s_p = \sqrt{\frac{(n_1 - 1)s_\text{x1}^2 + (n_2 - 1)s_\text{x2}^2}{n_1 + n_2 - 2}}\] \[\text{CI}_\text{mean difference} = (\bar{x}_B - \bar{x}_A) \pm t_\text{critical} * s_p * \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_A} + \frac{1}{n_B}}\]Where \(s_p\) is the pooled sample variance (estimate for population variance \(\sigma^2\)), and \(n_i − 1\) is the degrees of freedom for each group. The total degrees of freedom is the sample size minus two (n1 + n2 − 2).

Assumptions:

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- Assumes variances are equal (using the sample variances to calculate a pooled estimate of the population variance for the standard error).

- Assumes the means follow normal distributions (i.e. the sampling distribution of the estimator is normal).

In general, the t-test is fairly robust to all but large deviations from these assumptions. However, the equal variance assumption is often violated, so Welch’s t-test (which doesn’t assume equal variance) is more commonly used.

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import t

def ttest(group1, group2, alternative='two-sided', alpha=0.05):

'''

Run two sample independent t-test

group 1, 2: numpy arrays for data in each group (note, in AB testing, generally make group1 variant and group2 control so that the difference = variant - control).

alternative:

- two_sided: two-tailed test (Ha:mu1!=mu2). Checks upper tail: is abs(t) > critical t, using 1-alpha/2.

- greater: one-tailed test (Ha:mu1>mu2). Checks upper tail: is t > critical t, using 1-alpha.

- less: one-tailed test (Ha:mu1<mu2). Checks lower tail: is t < critical t, using alpha.

alpha: false positive rate (1-alpha = confidence level)

returns: t value, critical t value, p value, difference in means (group 1 - group 2), confidence interval lower and upper for the difference.

'''

n1 = len(group1)

n2 = len(group2)

var_a = group1.var(ddof=1)

var_b = group2.var(ddof=1)

sp = np.sqrt(((n1-1)*var_a + (n2-1)*var_b) / (n1+n2-2))

df = n1 + n2 - 2

mean_diff = group1.mean() - group2.mean()

t_value = mean_diff / (sp * np.sqrt(1/n1 + 1/n2))

if alternative == 'two-sided':

t_prob = t.cdf(abs(t_value), df)

t_critical = t.ppf(1 - alpha/2, df)

ci_lower = mean_diff - t_critical * np.sqrt( 1/n1 + 1/n2) * sp

ci_upper = mean_diff + t_critical * np.sqrt( 1/n1 + 1/n2) * sp

return t_value, t_critical, 2*(1-t_prob), mean_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper

elif alternative == 'greater':

t_prob = t.cdf(t_value, df)

t_critical = t.ppf(1 - alpha, df)

ci_lower = mean_diff - t_critical * np.sqrt( 1/n1 + 1/n2) * sp

ci_upper = None

return t_value, t_critical, 1-t_prob, mean_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper

elif alternative == 'less':

t_prob = t.cdf(t_value, df)

t_critical = t.ppf(alpha, df)

ci_lower = None

ci_upper = mean_diff + t_critical * np.sqrt( 1/n1 + 1/n2) * sp

return t_value, t_critical, t_prob, mean_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper

else:

print('Error: unknown alternative selected')

return None, None, None, None, None, None

np.random.seed(26)

x1 = np.random.normal(46, 3, 100)

x2 = np.random.normal(47, 3.5, 105)

tval, tc, pval, mean_diff, ci_low, ci_upp = ttest(group1=x1, group2=x2, alternative='two-sided', alpha=0.05)

print('t value = {:.4f}, pval = {:.4f}, 95% CI: {:.4f} to {:.4f}'.format(tval, pval, ci_low, ci_upp))

t value = -1.6242, pval = 0.1059, 95% CI: -1.5516 to 0.1500

Using Welch’s t-interval

Welch’s t-test is generally preferred as it doesn’t assume the groups have equal variance, but doesn’t perform any worse than a t-test if they do. Unlike the t-test above, Welch’s t-test doesn’t use a pooled variance estimate, instead using each sample’s variance in the denominator:

\[t = \frac{\bar{x_1} - \bar{x_2}}{\sqrt{\frac{s_1^2}{n1} + \frac{s_2^2}{n2}}}\] \[dof = \frac {(\frac{s_\text{x1}^2}{n1} + \frac{s_\text{x2}^2}{n2})^2}{\frac{s_\text{x1}^4}{n1^2*(n1-1)} + \frac{s_\text{x2}^4}{n2^2*(n2-1)}}\] \[\text{CI}_\text{mean difference} = (\bar{x}_2 - \bar{x}_1) \pm t_\text{critical} * \sqrt{\frac{s_\text{x1}^2}{n_1} + \frac{s_\text{x2}^2}{n_2}}\]The degrees of freedom is also different to the standard t-test (used to determine the t-distribution and thus critical value). Note, \(s_\text{x1}^4\), \(s_\text{x2}^4\) are just the squared sample variances.

Assumptions:

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- Assumes the means follow normal distributions (i.e. the sampling distribution of the estimator is normal).

from scipy.stats import t

import numpy as np

def welch_t_test(avg_group1, variance_group1, n_group1,

avg_group2, variance_group2, n_group2,

alternative='two-sided', alpha=0.05):

"""

Runs Welch's test to determine if the average value of a metric differs

between two independent samples. For AB testing, make group1 variant and group2 control (so difference = variant - control)

alternative:

- two_sided: two-tailed test (Ha:mu1!=mu2). Checks upper tail: is abs(t) > critical t, with alpha=1-alpha/2.

- greater: one-tailed test (Ha:mu1>mu2). Checks upper tail: is t > critical t, with alpha=1-alpha.

- less: one-tailed test (Ha:mu1<mu2). Checks lower tail: is t < critical t, with alpha=alpha.

Returns: t value, critical t, p value, mean difference, confidence interval upper and lower

"""

mean_difference = avg_group1 - avg_group2

mean_variance_group1 = variance_group1/n_group1

mean_variance_group2 = variance_group2/n_group2

se = np.sqrt(mean_variance_group1 + mean_variance_group2)

t_value = mean_difference / se

dof_numer = (mean_variance_group1 + mean_variance_group2)**2

dof_denom = ((mean_variance_group1)**2 / (n_group1-1)) + ((mean_variance_group2)**2 / (n_group2-1))

dof = dof_numer / dof_denom

if alternative == 'two-sided':

t_prob = t.cdf(abs(t_value), dof)

t_critical = t.ppf(1 - alpha/2, dof)

ci_lower = mean_difference - t_critical * se

ci_upper = mean_difference + t_critical * se

return t_value, t_critical, 2*(1-t_prob), mean_difference, ci_lower, ci_upper

elif alternative == 'greater':

t_prob = t.cdf(t_value, dof)

t_critical = t.ppf(1 - alpha, dof)

ci_lower = mean_difference - t_critical * se

ci_upper = None

return t_value, t_critical, 1-t_prob, mean_difference, ci_lower, ci_upper

elif alternative == 'less':

t_prob = t.cdf(t_value, dof)

t_critical = t.ppf(alpha, dof)

ci_lower = None

ci_upper = mean_difference + t_critical * se

return t_value, t_critical, t_prob, mean_difference, ci_lower, ci_upper

else:

print('Error: unknown alternative selected')

return None, None, None, None, None, None

np.random.seed(26)

group1 = np.random.normal(46, 3, 100)

group2 = np.random.normal(47, 3.5, 105)

tstat, t_critical, pval, mu_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper = welch_t_test(avg_group1=np.mean(group1),

variance_group1 = np.var(group1, ddof=1),

n_group1 = len(group1),

avg_group2=np.mean(group2),

variance_group2 = np.var(group2, ddof=1),

n_group2 = len(group2),

alternative = 'two-sided',

alpha=0.05)

print('t value = {:.4f}, pval = {:.4f}, CI = {:.4f} to {:.4f}'.format(tstat, pval, ci_lower, ci_upper))

t value = -1.6286, pval = 0.1050, CI = -1.5493 to 0.1477

Difference in independent proportions (normal approximation)

If the sampling distribution for the difference in proportions is normal, we can use a z-test:

\[z = \frac{(\hat{p_1} - \hat{p_2})}{\sqrt{p(1-p)(\frac{1}{n1} + \frac{1}{n2})}}\] \[p = \frac{x_1+x_2}{n_1+n_2}\]Where x1 and x2 are the number of successes in each group. Like the pooled estimate used in the two-sample t-test, the result for p will be between p̂1 and p̂2. The difference between the two groups is p̂1 minus p̂2, and the standard error for the difference is the standard error of p̂1 + the standard error of p̂2:

\[SE_\text{difference} = \sqrt{\frac{\hat{p_1}(1-\hat{p_1})}{n1} + \frac{\hat{p_2}(1-\hat{p_2})}{n2}}\] \[CI = \hat{p} \pm z_\text{critical} * SE_\text{difference}\]Assumptions

- Samples are independent and randomly selected.

- The binomial distribution is closely approximated by the gaussian distribution. This is true for large samples.

- Rule of thumb: expected successess and failures in both samples at least 10. If there are fewer, an exact test can be used.

import numpy as np

from scipy import stats

def z_test_2_sample_proportions(x1, x2, n1, n2, alternative='two-sided', alpha=0.05):

'''

Calculate the test statistic for a z-test on 2 proportions from independent samples.

Note, for AB testing make group 1 variant and group 2 control (so difference = variant - control).

x1, x2: number of successes in group 1 and 2

n1, n2: total number of observations in group 1 and 2

alpha: false positive rate (1-alpha=confidence)

alternative:

- two_sided: two-tailed test (Ha:mu1!=mu2). Checks upper tail: is abs(t) > critical t, with alpha=1-alpha/2.

- greater: one-tailed test (Ha:mu1>mu2). Checks upper tail: is t > critical t, with alpha=1-alpha.

- less: one-tailed test (Ha:mu1<mu2). Checks lower tail: is t < critical t, with alpha=alpha.

Returns: test statistic (z), p-value, confidence interval lower and upper bounds

'''

avg_p = (x1 + x2) / (n1 + n2)

z_val = (x1/n1 - x2/n2) / np.sqrt(avg_p * (1-avg_p) * (1/n1 + 1/n2))

p1 = x1 / n1

p2 = x2 / n2

prop_diff = p1 - p2

se = np.sqrt( (p1*(1-p1)) / n1 + (p2*(1-p2)) / n2)

if alternative == 'two-sided':

z_prob = stats.distributions.norm.cdf(np.abs(z_val))

critical_z = stats.norm.ppf(1 - alpha/2)

ci_lower = prop_diff - critical_z * se

ci_upper = prop_diff + critical_z * se

return z_val, critical_z, 2*(1-z_prob), prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper

elif alternative == 'greater':

z_prob = stats.distributions.norm.cdf(z_val)

critical_z = stats.norm.ppf(1 - alpha)

ci_lower = prop_diff - critical_z * se

ci_upper = None

return z_val, critical_z, 1-z_prob, prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper

elif alternative == 'less':

z_prob = stats.distributions.norm.cdf(z_val)

critical_z = stats.norm.ppf(alpha)

ci_lower = None

ci_upper = prop_diff + critical_z * se

return z_val, critical_z, z_prob, prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper

z_val, critical_z, pval, prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper = z_test_2_sample_proportions(x1=20, x2=25, n1=100, n2=102, alternative='two-sided', alpha=0.05)

print('Two sided (Ha:p1!=p2): z = {:.4f}, p value = {:.4f}, diff={:.3f}, CI= {:.4f} to {:.4f}'.format(z_val, pval, prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper))

z_val, critical_z, pval, prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper = z_test_2_sample_proportions(x1=20, x2=25, n1=100, n2=102, alternative='less', alpha=0.05)

print('One-sided (Ha:p1<p2) z-test: z = {:.4f}, p value = {:.4f}, CI= {:.4f} to {:.4f}'.format(z_val, pval, ci_lower, ci_upper))

z_val, critical_z, pval, prop_diff, ci_lower, ci_upper = z_test_2_sample_proportions(x1=20, x2=25, n1=100, n2=102, alternative='greater', alpha=0.05)

print('One-sided (Ha:p1>p2) z-test: z = {:.4f}, p value = {:.4f}, CI= {:.4f} to {:.4f}'.format(z_val, pval, ci_lower, ci_upper))

Two sided (Ha:p1!=p2): z = -0.7702, p value = 0.4412, diff=-0.045, CI= -0.1596 to 0.0694

One-sided (Ha:p1<p2) z-test: z = -0.7702, p value = 0.2206, CI= 0.0510 to -0.1412

One-sided (Ha:p1>p2) z-test: z = -0.7702, p value = 0.7794, CI= -0.1412 to 0.0510

Using statsmodels to test below. Note, confint_proportions_2indep by default does 2-sided by dividing alpha by 2. To do one-sided, multiply alpha by 2 in the inputs.

import numpy as np

from statsmodels.stats.proportion import proportions_ztest, confint_proportions_2indep

x1=20

x2=25

n1=100

n2=102

success_cnts = np.array([x1, x2])

total_cnts = np.array([n1, n2])

test_stat, pval = proportions_ztest(count=success_cnts,

nobs=total_cnts,

alternative='two-sided')

ci_lower, ci_upper = confint_proportions_2indep(count1=x1,

nobs1=n1,

count2=x2,

nobs2=n2,

method=None,

compare='diff',

alpha=0.05,

correction=False)

print('Two sided z-test: z = {:.4f}, p value = {:.4f}, CI= {:.4f} to {:.4f}'.format(test_stat, pval, ci_lower, ci_upper))

test_stat, pval = proportions_ztest(count=success_cnts,

nobs=total_cnts,

alternative='smaller')

print('One-sided (Ha:p1<p2): z = {:.4f}, p value = {:.4f}'.format(test_stat, pval))

test_stat, pval = proportions_ztest(count=success_cnts,

nobs=total_cnts,

alternative='larger')

print('One-sided (Ha:p1>p2): z = {:.4f}, p value = {:.4f}'.format(test_stat, pval))

Two sided z-test: z = -0.7702, p value = 0.4412, CI= -0.1585 to 0.0700

One-sided (Ha:p1<p2): z = -0.7702, p value = 0.2206

One-sided (Ha:p1>p2): z = -0.7702, p value = 0.7794

Confidence interval for ratio metrics (two independent samples):

For metrics that are actually the ratio of two variables, we need to estimate the expected value and variance of the ratio. This can be difficult. Two common methods for ratio metrics are Fieller’s theorem and the Delta method (also called Taylor’s method). I’ll demonstrate below with examples, but two common uses are:

- 1) Calculating a CI for the percentage difference instead of the absolute difference (e.g. percentage change in average spend). The percentage is sometimes easier to interpret and compare than the absolute difference (e.g. 10% increase is clear, whereas a $5 difference requires you to check the baseline to decide if it’s large).

- 2) Calculating a CI for a ratio where the denominator is not the unit of randomisation (e.g. clicks/views when the experiment randomised visitors). In this case the observations are not independent.

Fieller’s method (example for percentage change)

The variance of the difference, variance(meanA - meanB), is simply variance(meanA) + variance(meanB). However, the variance of the percentage difference = variance((meanB-meanA)/meanA) = variance(meanB/meanA), which is a ratio metric. Therefore, we can’t just convert the absolute difference CI bounds to percentages by dividing by the control group (dividing by the control results in a higher variance).

Given the two means come from normal distributions, they are jointly bivariate normal, and the ratio is also normally distributed. Fieller’s theorem gives an approximate confidence interval for a ratio of means in this scenario:

def ci_ratio_means(confidence, avg_control, stdev_control, n_control,

avg_treatment, stdev_treatment, n_treatment):

"""

Computes the confidence interval for the ratio of means using Fieller's method

confidence: Confidence level for interval e.g. 0.95 for 95% (alpha=0.05)

avg_control: Sample mean for the control group

avg_treatment: Sample mean for the treatment group

stdev_control: Sample standard deviation for the control group

stdev_treatment: Sample standard deviation for the treatment group

n_control: Number of observations in the control sample

n_treatment: Number of observations in the treatment sample

Returns: estimated percentage difference, upper and lower bounds for the confidence interval

"""

pct_change_estimate = (avg_treatment - avg_control) / abs(avg_control)

zsq = stats.norm.ppf(1 - (1-confidence)/2)**2

a = avg_control * avg_treatment

b = avg_control**2 - (zsq * stdev_control**2 / n_control)

c = avg_treatment**2 - (zsq * stdev_treatment**2 / n_treatment)

disc = a**2 - (b*c)

if (disc <= 0 or b<=0):

print('CI can\'t be computed')

return pct_change_estimate, None, None

sroot = np.sqrt(disc)/b

ci_lower = a/b - sroot - 1

ci_upper = a/b + sroot - 1

if (avg_control < 0):

ci_lower = ci_lower * -1

ci_upper = ci_upper * -1

return pct_change_estimate, ci_lower, ci_upper

def ci_ratio_proportions(confidence, successes_control, successes_treatment, n_control, n_treatment):

"""

Computes the confidence interval for the percentage difference in a binomial metric using Fieller's method

"""

avg_control = float(successes_base)/n_control

avg_treatment = float(successes_treatment)/n_treatment

stdev_control = np.sqrt((avg_control-avg_control**2))

stdev_treatment = np.sqrt((avg_treatment-avg_treatment**2))

return ci_ratio_means(confidence, avg_control, stdev_control, n_control,

avg_treatment, stdev_treatment, n_treatment)

References:

- Code from sas

- Ratios: A short guide to confidence limits and proper use (Franz, 2007)

- Wikipedia

Delta method:

The other common option is the delta method (also known as Taylor’s method), which uses a linear approximation for the estimates making it simpler to calculate a CI. Though Fieller’s method is better for small samples, the Delta method is simpler to implement.

Given two independent means x_c and x_t (control and treatment), the variance is estimated as:

\[variance(\%\Delta) = \frac{1}{\hat{x_c}^2} * var(\hat{x_t}) + \frac{\hat{x_t}^2}{\hat{x_c}^4} * var(\hat{x_c})\]References:

- Applying the Delta method in metric analytics: A practical guide with novel ideas (Deng et al, 2018)

- A Python implementation from that paper (github)

Bootstrap method

Sometimes the confidence interval is not defined, or difficult to compute. For example, the difference in the 90th percentiles (common for metrics like page load time), or even the difference in means of non-normal distributions with smaller sample sizes (where the difference hasn’t converged to normal yet). In these cases, we can use bootstrapping. Bootstrapping makes no assumptions about the distribution. Instead, we simulate multiple experiments by resampling multiple times from the original sample (randomly selecting the same n each time, with replacement). For each new sample we calculate the statistic we are estimating (e.g. the 90th percentile), and save it. The distribution of these estimates gives us an estimate of the sampling distribution, and it’s standard deviation is an estimate of the standard error. If the distribution is normal, we can simply use the percentiles to get a CI (e.g. 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles for a 95% CI):

\[\text{Percentile CI} = 100*(\frac{\alpha}{2}), 100*1-(\frac{\alpha}{2})\]However, if it’s non-normal, we might over/underestimate the CI with this method, so it’s better to use a bias-correcting method (e.g. BCa). Read more on this here.

The downside of this method is that it can be slow, particularly if your working with large samples. However, there are some tricks for optimising it.

Final thoughts

- The confidence interval measures the uncertainty of a sample statistic as an estimate for a population parameter (i.e. it’s estimating the reliability of the estimation process). It’s based on how much estimates would vary across repeated experiments (the sampling distribution).

- An intuitive way to describe it is ‘a range of plausible values’. We don’t know where the population value lies within the interval, but we are reasonably confident it’s somewhere within the bounds. If we are ok with the upper/lower bound being true, we can proceed with our action.

- However, the population value is either within the interval or not. We can say with 95% confidence, if we repeat an experiment many times, the interval will contain the population value 95% of the time. The other 5% of the time, it’s not in the interval at all. So the upper/lower bounds may not actually be the best/worst case scenario.

- This is to say, it’s technically incorrect to describe the confidence as the probability a given CI contains the population value. It’s a fixed value not a variable, and the pop. value is in it or not (i.e. probability is 0 or 100%). However, it’s not uncommon to hear something like “we are 95% confident the interval includes the population mean”. Just keep in mind this refers to the proportion of samples with repeated sampling, not this particular interval.

- There are a few factors that will change the width of the interval: the sample size (larger sample = more narrow interval), the variance of the metric (smaller variance = more narrow interval), and the confidence level (higher confidence level = smaller alpha = wider interval).

- The confidence interval and p-value are communicating the same information in different ways. They will always agree, assuming the settings and sample are the same (i.e. for the null hypothesis that the difference in means is 0, if the p-value is significant, the confidence interval for the difference won’t overlap 0).

- Generally we can estimate the sampling distribution by using the standard normal curve. However, there are many other methods out there. For ratio metrics, we have Fieller’s method, and the delta method. For non-normal distributions, we have bootstrapping.

References:

- Scottish government’s advice on CIs

- Confidence Intervals & P-values for Percent Change / Relative Difference Georgiev, 2020