Metric validation for AB testing

In AB testing, the t-test is one of the most commonly used tests. However, if the assumptions are not met, the results are not valid. A key assumption we make is that the means come from a normal distribution. The central limit theorem (CLT) tells us that for average metrics with finite variance, the sampling distribution will converge to normal as n increases (regardless of whether the observed metric distribution is normal or not). However, this requires that the sample size is ‘large enough’ to converge, and that will depend on the metric distribution (e.g. a very skewed metric can require a large sample to converge). In this post I’ll explain a very simple approach to test the validity of the t-test p-value using simulation. It’s largely inspired by this Microsoft article, but I’ve also seen this in practice in other organisations.

The problem

Recall that in a t-test we assume that the null distribution follows a t-distribution, which quickly converges to normal with large samples. We assess the observed difference against the t-distribution, and reject the null hypothesis if it is sufficiently uncommon. By setting the threshold for significance at 0.05, we expect that when the null hypothesis is true (no difference), we will incorrectly conclude there is a difference 5% of the time (type I error). Given we know the null hypothesis is true in an A/A experiment (no difference, two control groups), 5% of the time we should see a p-value <0.05, 10% it should be <0.1 and so on. However, if the actual sampling distribution is not well approximated by the assumed t distribution, then our false positive rates can be higher/lower than expected and the results are not valid.

Simulating A/As

To test the above assumption about the p-values, we can simulate A/As from sample data. For the sample you can use a similar past experiment, the current experiment (if doing post), or historical data (taking care to simulate experiment settings, e.g. each ID counted only once and data is from ‘entry’ into the experiment). If you’re using experiment data, combine the control/variants into one sample. Now randomly split the data into 2 groups many times (replicating whatever split you are using by changing the probability of selection, e.g. 50/50, 90/10). For each A/A pair we run our planned statistical test (e.g. t-test). As mentioned earlier, if the test is valid, the sampling distribution (mean difference estimates) should be approximately normal and centered on 0, and the p-values should be uniformly distributed (5% below 0.05, 10% below 0.1 and so on).

Examples

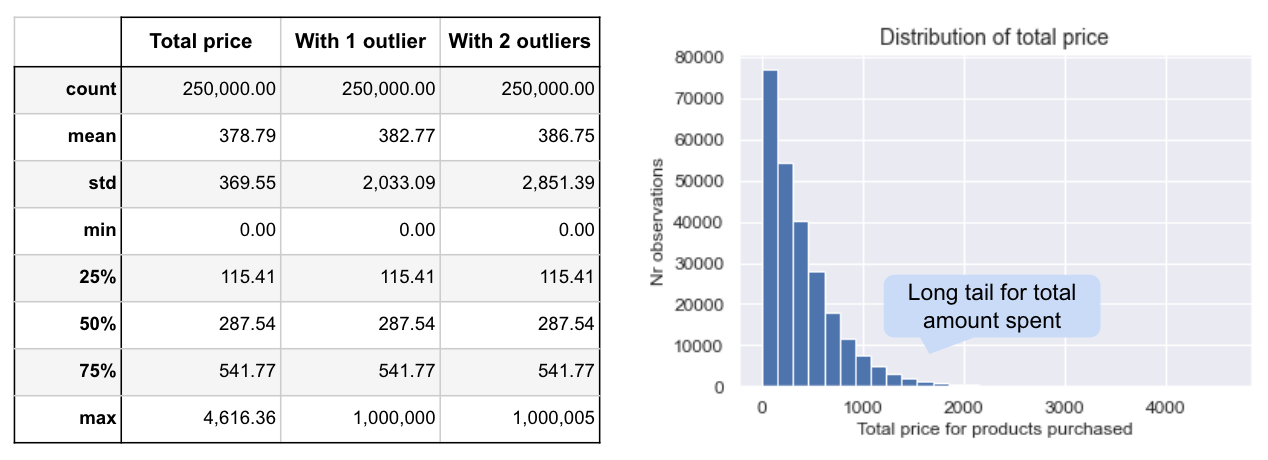

It’s easier to understand this with some examples. To demonstrate, we look at the metric ‘total price’ (the total amount spent on purchases per visitor) in a sample of 250K observations, re-sampled repeatedly to create 200 simulated A/As. I’ve created 3 versions: the original skewed metric (shown below); the highest value increased to add a single large outlier; and, the two highest values increased to create two large outliers.

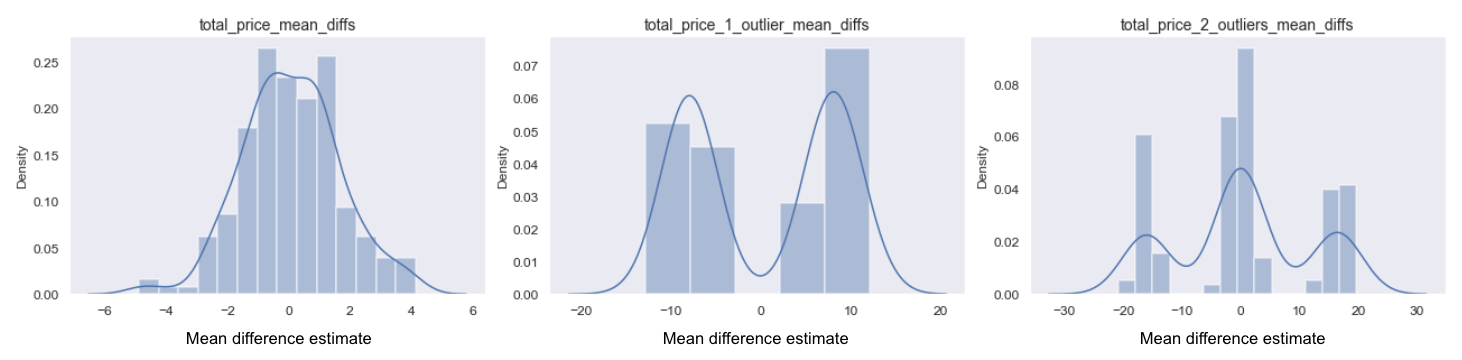

The sampling distribution for the original metric (left) is approximately normal, despite the metric being skewed (as our sample is relatively large so CLT kicked in). However, when we add one or two outliers, we see it becomes bi-modal with 1 outlier, and tri-modal with 2 outliers. In the single outlier case this happens because we either get a large positive or negative effect depending on which group the outlier lands in. With two outliers, we also get the two clusters on either end when both outliers are in one group, and then another cluster in the middle when we get one outlier in each group.

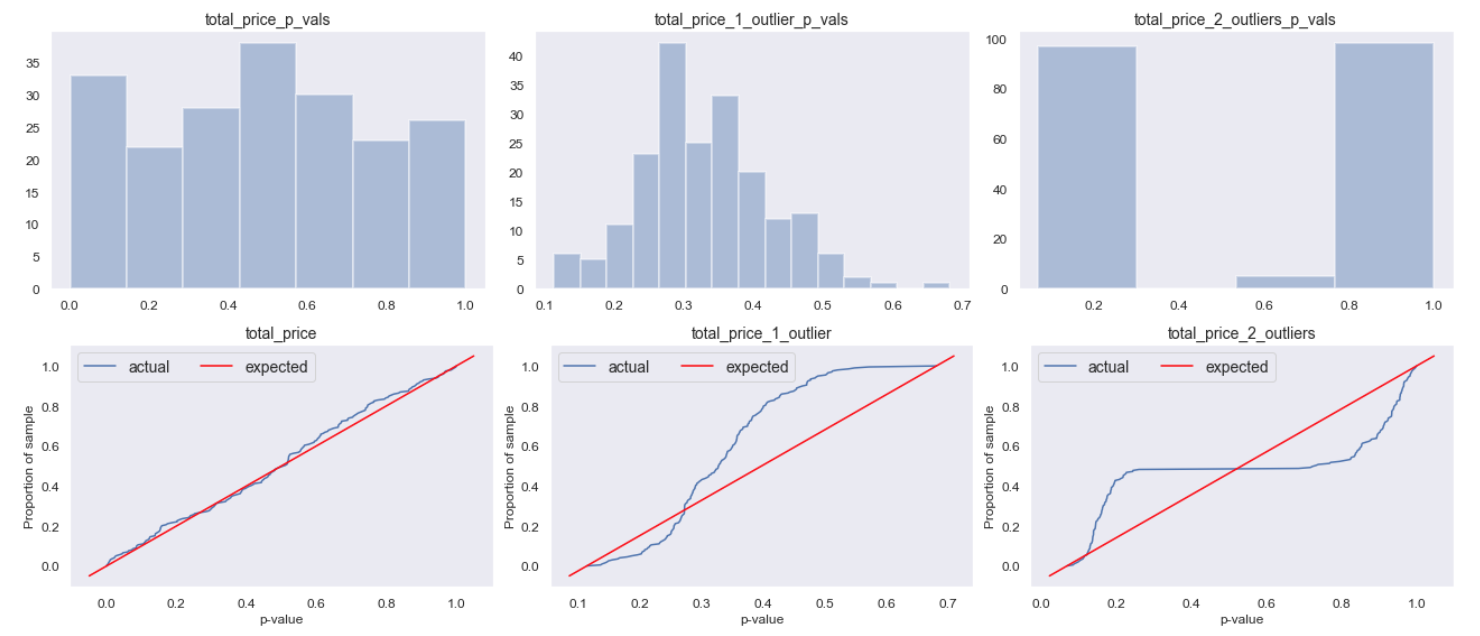

In line with the sampling distribution, below we see that the p-values are approximately uniform for the original metric (left), but far from the assumed distribution with outliers (as a result of the inflated mean and variance). With a single outlier, the t-value is a bit over 1 each simulation, resulting in the cluster of p-values around ~0.33. We know from the 68-95-99.7 rule that ~68% of the data is within 1 standard deviation, meaning 32% is outside that. Thus if our t-value is 1 we would expect a p-value of 0.32 (how often we expect results at least as extreme). This is why we get the cluster around 0.33. In the two outlier case, we get the peak on the left from when the outliers are in the same group, and another peak on the right when the outliers are in different groups. In both outlier cases, it’s clear the p-value uniform our false positive rate is clearly not behaving as assumed.

Tests

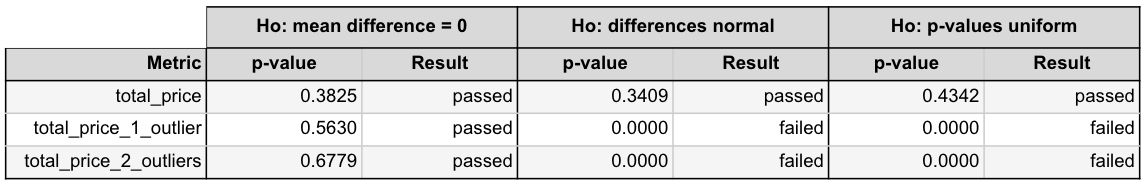

To support the visual inspection, we can also formalise these checks with some statistical tests:

- T-test on the mean differences: we can run a one sample t-test on the mean difference distribution to assess whether the mean differs from 0. If the result is significant (differs from 0), we mark it as ‘failed’, as the assumed null distribution is centered on 0.

- Shapiro test on mean differences: This test compares the mean difference distribution to a normal distribution. If the result is significant than it deviates from the assumed normal distribution (for large samples) and we mark it as ‘failed’. Note, with really large samples, this can fail even when you draw the sample from a normal distribution. So use your judgement here, it only needs to be approximately normal.

- Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test on p-values: This test compares the p-value distribution to a uniform distribution. Again, if the result is significant it deviates from the assumed uniform distribution and we mark it as ‘failed’.

Examples

Below are the results for the examples above. As we expect based on the plots, the Shapiro test for normally-distributed mean differences and the KS test for uniform p-values both failed for the metrics with outliers. Keep in mind though that these should be used in combination with the visual plots and a bit of common sense.

Common causes and solutions

If the p-values are not uniform (and thus this test is not valid for our metric), there are a few common causes you can check:

- 1) Outliers: Unusual observations far from the mean increase the variance, resulting in a higher standard error in the denominator and lower power (i.e. test statistic will be smaller, all else equal). By chance, one or both samples may get a small number of outliers which are likely not caused by the treatment. It’s generally recommended that you cap the metric at some reasonable threshold in these cases to remove them. For example, winsorize the metric, capping the values at the 99th percentile (replacing them with the value of the 99th percentile). When you do this, combine both groups to calculate the 99th percentile and then use that value to replace any values greater than it in both groups (apply the same rule to both groups to avoid introducing bias).

- 2) Skewed / non-normal metrics: Sometimes the sample size is insufficient for the sampling distribution to converge if the metric is very skewed or non-normal. In this case you can try a larger sample (run a longer experiment), or transform the data (e.g. if it’s log-normal, take the log of the metric). Note, if you choose to transform the metric, be aware of the implications (e.g. a t-test on log transformed data compares the geometric mean, which is not always desirable).

- 3) Mixed distributions: In some settings you may have distinct populations within your sample that behave differently (mean and variance different). If there is one dominant group, it may even just look like a skewed distribution or outliers. For example, if you have business and individual users, or merchants with multiple shops vs those with just one. In this case you may find using a regression to control for these pre-treatment factors helps reduce the variance.

- 4) Rare events: In the Microsoft article they showed another example where over the 200 simulations there were only 8 unique p-values. This occurs when the metric is measuring something very rare (e.g. a button that’s clicked extremely rarely). In this example there were only 15 observations with a value, and so there are only so many ways to split them into two groups, and as a result a limited number of possible p-values. In cases like this, there’s simply not enough observations with a value to detect any meaningful difference. We shouldn’t use the metric.

For most of these solutions you can try them on your sample data and re-run the simulations to confirm the assumptions are now met. For outliers and skewed data, you can also consider non-parametric tests which don’t make these assumptions about the distribution. For example, if you’re working with non-financial metrics, the Mann-Whitney u-test is a good alternative (comparing the ranks). More on this in my post here.

Code

I’m using Welch’s t-test as it’s recommended over the standard t-test. See here for more details. I’ve only tested this on two-sided tests, but there’s some discussion here for one-sided tests.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind_from_stats, ttest_1samp, shapiro, kstest, t

from scipy.stats.mstats import winsorize

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import math

pd.options.display.max_rows = 999

pd.options.display.max_columns = 999

pd.options.display.max_colwidth = 999

plt.style.use('ggplot')

sns.set(style='dark')

Part 1: Function to simulate AAs from a sample

def simulate_aa(df, continuous_metrics, n_bootstrap_runs, base_sample_frac=0.5):

"""

Simulate AAs by randomly splitting provided df into 2 multiple times.

:param df: Pandas DF with 1 row per ID and the metrics to be tested.

:param n_bootstrap_runs: Number of simulations to run (times to split data into AAs).

:param base_sample_frac: Proportion of sample that should be in the control group (0.5=50% by default).

:return: Pandas DataFrame with p_values, counts, and mean differences for each metric tested, per A/A.

"""

metrics_df = pd.DataFrame({'round': [],

'metric': [],

'p_value': [],

'base_cnt': [],

'var_cnt': [],

'mean_difference': []

})

for r in range(0, n_bootstrap_runs):

a1 = df.sample(frac=base_sample_frac, replace=False)

a2 = df.drop(a1.index)

metric_name = []

p_values = []

round_nr = []

base_cnt = []

var_cnt = []

mean_diffs = []

for cm in continuous_metrics:

round_nr.append(r)

metric_name.append(cm)

avg_a1 = a1[cm].mean()

avg_a2 = a2[cm].mean()

mean_diff = avg_a2 - avg_a1

std_a1 = a1[cm].std()

std_a2 = a2[cm].std()

# Welch's t-test

t_val, p_val = ttest_ind_from_stats(mean1=avg_a1, std1=std_a1, nobs1=len(a1),

mean2=avg_a2, std2=std_a2, nobs2=len(a2),

equal_var=False)

p_values.append(p_val)

base_cnt.append(len(a1))

var_cnt.append(len(a2))

mean_diffs.append(mean_diff)

p_val_df = pd.DataFrame({'round': round_nr,

'metric': metric_name,

'p_value': p_values,

'base_cnt': base_cnt,

'var_cnt': var_cnt,

'mean_difference': mean_diffs

})

metrics_df = metrics_df.append(p_val_df)

metrics_pvals = metrics_df.pivot(index='round', columns='metric', values='p_value').reset_index()

metrics_diffs = metrics_df.pivot(index='round', columns='metric', values='mean_difference').reset_index()

return metrics_df, metrics_pvals, metrics_diffs

Part 2: Function to plot p-values and mean differences

def simulation_plots(metrics_df, metrics_pvals, metrics_diffs, continuous_metrics):

"""

Take simulated AA results and return plots for the distribution of p-values and mean differences.

:param metrics_df: Pandas DF with one row per simulated sample and metric.

:param metrics_pvals: Pandas DF with p-values per metric (column) and A/A (row).

:param metrics_diffs: Pandas DF with the mean difference per metric (column) and A/A (row).

:param continuous_metrics: List of continuous metrics to test.

:return: Distribution plots for p-value and mean differences.

"""

# Plot p-vals

columns_n = len(continuous_metrics)

rows_n = int(np.ceil(len(continuous_metrics)/columns_n))

fig, axs = plt.subplots(rows_n, columns_n, figsize=(columns_n*6, rows_n*4), sharey=False, sharex=False, squeeze=False)

for i, ax in zip(range(len(continuous_metrics)), axs.flat):

col_i = continuous_metrics[i]

sns.histplot(data=metrics_pvals[col_i].values, kde=False, ax=ax,

cbar_kws=dict(edgecolor="w", linewidth=2))

ax.set_title(col_i+'_p_vals', fontsize=14)

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Plot cumulative p-val distribution (proportion of sample below value)

columns_n = cols_in_plot

rows_n = int(np.ceil(len(continuous_metrics)/columns_n))

fig, axs = plt.subplots(rows_n, columns_n, figsize=(columns_n*6, rows_n*4), sharey=False, sharex=False, squeeze=False)

for i, ax in zip(range(len(continuous_metrics)), axs.flat):

col_i = continuous_metrics[i]

data_sorted = np.sort(metrics_pvals[col_i].values)

p = 1. * np.arange(len(metrics_pvals)) / (len(metrics_pvals) - 1)

ax.plot(data_sorted, p, label='actual')

ax.plot(ax.get_xlim(), ax.get_ylim(), ls="-", label='expected', color='red')

ax.set_ylabel('Proportion of sample')

ax.set_xlabel('p-value')

ax.set_title(col_i, fontsize=14)

ax.legend(loc=2, ncol=2, fontsize=14)

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Plot mean differences distribution

columns_n = cols_in_plot

rows_n = int(np.ceil(len(continuous_metrics)/columns_n))

fig, axs = plt.subplots(rows_n, columns_n, figsize=(columns_n*6, rows_n*4), sharey=False, sharex=False, squeeze=False)

for i, ax in zip(range(len(continuous_metrics)), axs.flat):

col_i = continuous_metrics[i]

sns.histplot(data=metrics_diffs[col_i].values, kde=True, ax=ax,

cbar_kws=dict(edgecolor="w", linewidth=2))

ax.set_title(col_i+'_mean_diffs', fontsize=14)

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

return fig

Part 3: Function to run tests on the p-values and metric differences

def simulation_tests(metrics_diffs, metrics_pvals, continuous_metrics, df, n_bootstrap_runs=200, alpha=0.05):

"""

Simulate AAs and return test results for metric validity (t-test and shapiro on mean differences,

ks test on p-values).

:param metrics_diffs: Pandas DF with the mean difference per metric (column) and A/A (row).

:param metrics_pvals: Pandas DF with p-values per metric (column) and A/A (row).

:param continuous_metrics: List of continuous metrics to test.

:param df: Pandas DF with 1 row per ID and the metrics to be tested (in case need to re-run simulation).

:param n_bootstrap_runs: Number of simulations to run (times to split data into AAs).

:param alpha: Alpha level for significance, default = 0.05.

:return: Pandas dataframe with test results per metric.

"""

metric_names = []

zero_test_pvals = []

normality_test_pvals = []

uniformity_test_pvals = []

for cm in continuous_metrics:

# t-test on mean differences, Ho: mu=0

z_tstat, z_p_val = ttest_1samp(metrics_diffs[cm].values, popmean=0, axis=0)

# Shapiro test on mean differences, Ho: normal distribution

n_tstat, n_p_val = shapiro(metrics_diffs[cm].values)

# KS test on p-values, Ho: uniform distribution

u_tstat, u_p_val = kstest(metrics_pvals[cm].values, "uniform")

# If KS test significant, re-test

# Only 0.05*0.05=0.0025 change of being significant again if actually uniform.

if u_p_val > alpha:

uniformity_test_pvals.append(u_p_val)

else:

print('Retesting {} for uniformity'.format(cm))

# Re-run simulations

metrics_df_v2, metrics_pvals_v2, metrics_diffs_v2 = simulate_aa(df=df,

continuous_metrics=[cm],

n_bootstrap_runs=n_bootstrap_runs)

# Re-test

u_tstat_v2, u_p_val_v2 = kstest(metrics_pvals_v2[cm].values, "uniform")

uniformity_test_pvals.append(u_p_val_v2)

print('2nd p-value = {}'.format(u_p_val_v2))

metric_names.append(cm)

zero_test_pvals.append(z_p_val)

normality_test_pvals.append(n_p_val)

test_results_df = pd.DataFrame({'metric': metric_names,

'zero_test_pval': zero_test_pvals,

'normality_test_pval': normality_test_pvals,

'uniformity_test_pval': uniformity_test_pvals

})

test_results_df['zero_test_result'] = test_results_df['zero_test_pval'].map(lambda x: 'passed' if x > alpha else 'failed')

test_results_df['normality_test_result'] = test_results_df['normality_test_pval'].map(lambda x: 'passed' if x > alpha else 'failed')

test_results_df['uniformity_test_result'] = test_results_df['uniformity_test_pval'].map(lambda x: 'passed' if x > alpha else 'failed')

return test_results_df

Part 4: Run the AA simulations, plot and return results

def simulate_aa_tests(df, continuous_metrics, n_bootstrap_runs=200, alpha=0.05):

"""

Simulate A/As and return test results for metric validity (t-test and shapiro on mean differences, ks test on p-values).

:param df: Pandas DF with 1 row per ID and the metrics to be tested.

:param continuous_metrics: List of continuous metrics to test.

:param n_bootstrap_runs: Number of simulations to run (times to split data into A/As).

:param alpha: Alpha level for significance, default = 0.05.

:return: 4 Pandas DataFrames:

1) metrics_df: p_values, counts, and mean differences for each metric tested (1 per A/A and metric).

2) metrics_pvals: p-values per metric (column) and A/A (row).

3) metrics_diffs: mean difference per metric (column) and A/A (row).

4) test_results_df: results of tests on p-value and mean difference distributions.

"""

metrics_df, metrics_pvals, metrics_diffs = simulate_aa(df, continuous_metrics, n_bootstrap_runs)

fig = simulation_plots(metrics_df, metrics_pvals, metrics_diffs, continuous_metrics)

test_results_df = simulation_tests(df, metrics_diffs, metrics_pvals, continuous_metrics, n_bootstrap_runs=200, alpha=0.05)

return metrics_df, metrics_pvals, metrics_diffs, test_results_df

Notes:

- In my own experience, I come across metrics that fail these checks on a semi-regular basis. Particularly for new metrics, or metrics that were designed for other products with a larger sample size. In the Microsoft article they mention that for a typical product, ~10-15% of the metrics failed the test for uniform p-values under the null.

- It’s also worth mentioning that we can’t test once and forever assume the metric is ok. Products change, users change, and over time it’s possible there can be outliers and issues that were not previously detected. However, at a minimum it’s good to test at least once when you create a new metric.

- For binary metrics they are by definition binomial, so there is no need to validate. We would only see deviations from the expected p-values if there was some error in our calculations. Therefore, the focus here is on continuous metrics.

- Don’t forget to also think about the other assumptions. For example, we generally assume the observations are independent and randomly selected. In practice, there’s a number of ways the observations may be correlated, for example: relationships between customers; non-unique ID used for randomisation (e.g. http cookie or multi-device users might be counted more than once); and/or, shared supply (meaning what happens in variant impacts those in control).