Logistic regression: theory review

Logistic regression is a model used to predict a binary outcome (dependent variable) based on a set of features (independent variables). For example, it could be applied to customer browsing data to predict whether they will convert during that session (0 = no, 1 = yes). The model estimates the probability that the outcome belongs to one of the two classes (the one labeled 1) by predicting the log odds of the outcome as a linear function of the predictors. Since linear functions have an unbounded range, we use log odds (which range from −∞ to +∞) rather than the probability itself (which ranges from 0 to 1). The logistic (sigmoid) function then maps the log odds into the 0-1 range, transforming it into a probability. To estimate the coefficients (weights for each feature), we minimize the negative log likelihood using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) through an iterative optimization algorithm, as there is no closed-form solution. There are several assumptions that must be met for valid inference, including linearity (between the log odds and the features), the absence of multicollinearity (highly correlated features), and no endogeneity (where features are correlated with the error term). Additionally, the model requires a sufficiently large sample size and no influential outliers. These assumptions are similar to linear regression but differ in some respects due to the model’s structure and the binary outcome (for example, heteroskedasticity in the error is inherent). When these assumptions are properly addressed, logistic regression provides a simple yet effective approach to classification, offering valuable insights into the predictive factors driving the binary outcome.

How it works

Logistic regression is used for binary outcomes, meaning it has two classes that we label “0” (event didn’t occur) or “1” (event occured). We want to predict the probability of the event occuring (Y=1), given the features (X): \(P(Y=1 \mid X)\). As probabilities range from 0-1, we can’t directly fit a linear model on them. Instead we convert the outcome to the log odds (the natural logarithm of the odds of being “1” vs “0”), which ranges from −∞ to +∞. We then use an iterative process to identify the linear combination of the features that increases the likelihood of detecting the observed outcome (Maximum Likelihood Estimation). Through this process we find our estimated coefficients for each feature, and the predicted probability of “1” for each observation. In this section I’ll go through the process.

Outcome: probability -> log odds

To understand the connection between the log odds, odds, and probability of the outcome, it’s helpful to work through an example. Let’s assume we’re looking at one observation (one user session), where the probability of converting is 0.8 (80%).

Formula view

The odds is the ratio of the probability of the event happening, to the probability of it not happening, with a possible range of 0 to +∞. If the probability is 0.8, the odds is 4 to 1, meaning it’s 4 times as likely to occur than not (for every 1 time it doesn’t occur, it occurs 4 times).

\[\text{Odds}(Y=1 \mid X) = \frac{P(Y=1 \mid X)}{1 - P(Y=1 \mid X)} = \frac{0.8}{0.2} = 4\]The log odds is the natural logarithm of the odds, and ranges from −∞ to +∞. If it’s positive, it means the event is more likely to occur than not. If it’s 0, the odds are 1:1 (equally likely to occur or not occur). If it’s negative, the event is more likely to not occur than to occur. In our example it’s positive, re-iterating that it’s more likely to occur than not.

\[\text{Log Odds}(Y=1 \mid X) = \log \left( \frac{P(Y=1 \mid X)}{1 - P(Y=1 \mid X)} \right) = \log(4) \approx 1.386\]We can then reverse this process to convert the log odds back to the probability:

\[P(Y=1 \mid X) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-\text{Log Odds}}} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-1.386}} = 0.8\]The predicted outcome is then found by applying a decision boundary to the predicted probability (typically 0.5). In our example the prediction would be “1”, meaning we predict they converted:

\[\hat{Y} = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } p >= 0.5 \\ 0 & \text{if } p < 0.5 \end{cases}\]Visualising the connection

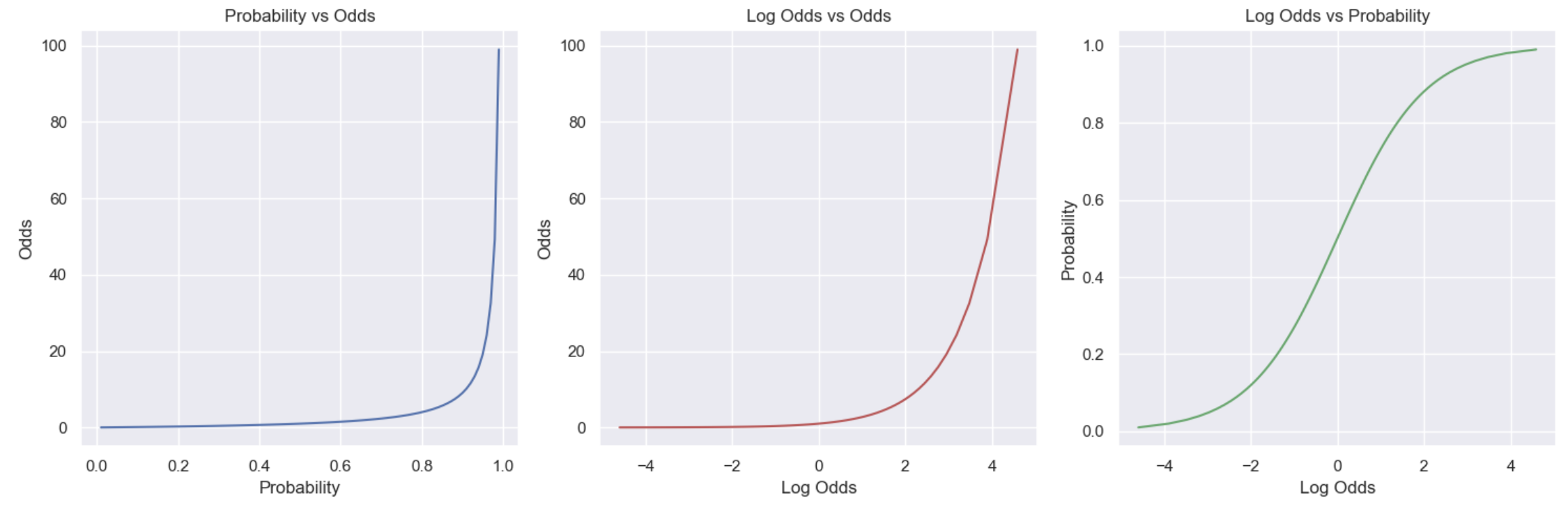

Let’s now look at a range of values to see how the three values relate. In the first plot we see that as the probability increases, the odds increase non-linearly (grow exponentially): as the probability approaches 0 the odds approach 0, and as it approaches 1 the odds approach infinity. The second plot converts the odds to log odds: as the odds increase, the log odds increase. Then the third plot is the one we’re really interested in, it compares the log odds to the original probability values, showing the sigmoid (S) curve relationship between them. This visualises what we said earlier: negative values mean the probability is < 0.5 (more likely not to occur than to occur); 0 means equal chance (p=0.5); and, positive values mean the probability is >0.5 (it’s more likely to occur than not).

Logistic model

Given the feature values (X’s), we want to determine the weights (coefficients or β), that when applied to our training data, give us predicted probabilities (\(\hat{P}(Y=1)\)) as close as possible to the actual binary outcomes (Y). We do this by finding the linear combination of the features that maximizes the likelihood of the log odds.

Logistic model:

\[\text{Log Odds} = \log \left( \frac{P(Y = 1 \mid X)}{1 - P(Y = 1 \mid X)} \right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n\] \[P(Y = 1 \mid X) = \sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1+e^{-z}} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n)}}\]Where:

- \(\beta_0\) is the intercept (value of Y when all X=0). Without this we would assume Y=0 when all X=0 and force the line to pass through the origin (Y=0, X=0). This might not make sense, but can also bias the \(\beta_n\) coefficients. Including \(\beta_0\) allows the line to shift up/down the Y axis to pass through the middle of the points, reducing the error.

- \(\beta_n\) are the weights for each feature \(X_n\) (change in Y for a 1 unit change in X).

- \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function which squashes its input (z: the linear combination of the features) into a value between 0 and 1, which makes it interpretable as a probability.

You may notice the similarities between the logistic model formula above and linear regression. Both models are fitting a linear function involving a set of features (X) and corresponding weights (β coefficients). The commonality is a major advantage of logistic regression, but note there are two key differences: 1) the \(\hat{Y}_i\) is a binary outcome (0/1) instead of continuous; and, 2) the linear function is expressed in the logit scale (\(e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n)}\)). Given point 1, we require point 2. Linear functions have an unbounded range, so they can predict any real number, including values far outside the range of [0, 1]. Similarly, the odds range from 0 to +∞, and can be extremely large or small, making it difficult to model and interpret. The log odds on the other hand ranges from −∞ to +∞, which allows us to fit a linear relationship between the features and the outcome using standard linear regression techniques. We are then able to convert the log odds to a probability using \(P(Y = 1 \mid X) = \sigma(z) = \frac{1}{1+e^{-z}} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n)}}\). Which is different to directly using the probabilities (which has the range issue above): \(P(Y = 1 \mid X) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n\).

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

Logistic regression is estimated using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). The idea is to find the coefficients that make the observed data most likely, or in other words, maximise the likelihood function. Let’s break down the formula.

Likelihood of one observation

Given our m observations (rows):

- \(X^i\) represents the features for the \(i^\text{th}\) observation

- \(y^i\) represents the actual outcome label for the \(i^\text{th}\) observation (0 or 1)

- For each observation i (one row):

- \(P(y^i=1 \mid X^i)=σ(z^i)=\frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n)}}=\hat{p}^i\).

- \(P(y^i=0 \mid X^i)=1 - σ(z^i) = 1-\hat{p}^i\).

- Combining these into a single expression that can handle both outcomes we get: \(P(y^{i} \mid X^{i}) = \hat{p}^{i^{y^{i}}} \cdot (1 - \hat{p}^{i})^{1 - y^{i}}\), which returns \(\hat{p}^i\) if \(y^i=1\) and \(1-\hat{p}^i\) if \(y^i=0\)

Likelihood of all observations

The likelihood of the entire data set (\(L(\theta)\)) is the joint probability of all the observations. Given we assume each row is independent, this is just the product of the probabilities for each observation (i.e. we take the likelihoods from each row and multiply them together):

\[L(\theta) = \prod_{i=1}^{m} P(y^{i} \mid X^{i}) = \prod_{i=1}^{m} \left[ \hat{p}^{i^{y^{i}}} \cdot (1 - \hat{p}^{i})^{1 - y^{i}} \right]\]Log likelihood

To make the calculations easier and avoid working with very small numbers (products of small probabilities), we take the natural logarithm of the likelihood function to get the log-likelihood function. The logarithm of a product becomes a sum, so the product of individual likelihoods becomes a sum of log-likelihoods (i.e. it sums the log of the individual likelihoods for all observations in the dataset). This transformation makes it easier to optimise: it’s differentiable, concave, and more stable.

\[\ell(\theta) = \log L(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[ y^{i} \log(\hat{p}^{i}) + (1 - y^{i}) \log(1 - \hat{p}^{i}) \right]\]When the predicted probability is close to the actual outcome label, the log likelihood will be close to 0, and if it’s far off it will be a much larger negative value (contributing more significantly to the penalty). This is why maximising the log likelihood minimises the gap between the actual and predicted values. Let’s demonstrate that:

- If \(y^i=1\), the log likelihood is \(\log(\hat{p}^{i})\) since \(1-y^i=0\). When \(\hat{p}^{i}\) is close to 1 (good prediction), the log likelihood is close to 0 (e.g. \(log(0.9) \mid -0.1\)), and the lower it gets, the worse the prediction and the more negative the log likelihood becomes e.g. \(log(0.1) \mid -2.3\)).

- This also works for \(y^i=0\): the log likelihood is \(\log(1 - \hat{p}^{i})\). When \(\hat{p}^{i}\) is close to 0 (good prediction), \(1-\hat{p}^{i}\) is close to 1 and the log likelihood is close to 0 (e.g. \(log(1-0.1) \mid -0.1\)). The higher \(\hat{p}^{i}\) gets, the worse the prediction and the more negative the log likelihood becomes e.g. \(log(1-0.9) \mid -2.3\)).

Note, due to the non-linearity of the sigmoid function that maps the logs odds to the probability, there’s no closed form solution to this like in linear regression. Instead, we use iterative methods to optimise the model parameters.

Negative log likelihood

Given many of the common optimisation algorithms are designed to minimise the cost function not maximise it, we multiply the log likelihood function by -1 to get the negative log likelihood:

\[J(\theta) = - \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[ y^{i} \log(\hat{p}^{i}) + (1 - y^{i}) \log(1 - \hat{p}^{i}) \right]\]Optimisation

Now we have our cost function (negative log likelihood), we can use an optimisation algorithm to iteratively adjust the coefficients to find the values that minimise it (giving us the best fitting model). The negative log likelihood is convex (single minimum), smooth and differentiable, meaning we will converge to the minimum as long as the algorithm is set up correctly. However, some methods are more efficient than others. For logistic regression, the most common optimisation algorithms use either just the first derivative (first order methods, e.g. Gradient Descent), or both the first and the second derivative (second order methods, e.g. Newton’s method). The second order methods are typically faster to converge, but are more computationally expensive. The default in statsmodels for logistic regression is a version of Newton, and scikit-learn uses an approximation of Newton (L-BFGS).

General framework

The basic process of these iterative optimisation algorithms is the same:

- Start with some values for the unknown model parameters (\(\beta\) coefficients), usually a vector of 0’s or small random values (we’ll call the vector \(\theta\)).

- Predict the probability of the outcome being “1” for each observation \(\hat{p}^{i} = \sigma(X^i \cdot \theta) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n)}}\)

- Compute the cost function (negative log likelihood): \(J(\theta) = - \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[ y^{i} \log(\hat{p}^{i}) + (1 - y^{i}) \log(1 - \hat{p}^{i}) \right]\)

- Compute the partial derivative(s) for each \(\beta\) (i.e. \(\theta\) in the above).

- Apply the update rule to update the \(\beta\) estimates in \(\theta\). Increase/decrease depending on if the outcome was over or under predicted.

- Repeat for a fixed number of steps (iterations), or until the convergence criteria is met (change in the cost function is smaller than a cutoff).

First Derivative

The first derivative tells us the gradient of the cost function, giving us the direction in which the function is increasing or decreasing. The first derivative of the negative log likelihood with respect to \(\theta_{j}\) is:

\[\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_j} = \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left( \sigma(X_i \cdot \theta) - y_i \right) X_{ij}\]Where:

- \(\theta_{j}\) is the \(j^{th}\) parameter (coefficient)

- \(X_{j}^{i}\) is the \(j^{th}\) feature of the \(i^{th} observation\)

- \(\sigma(X_i \cdot \theta)=\hat{p}_i\) is the predicted probability for the \(i^{th} observation\)

- The derivative for the intercept (bias) is the same, but \(X_{ij}=1\), so it can be ignored.

If you look at the formula, it’s taking the error (difference between the predicted probability and actual y label), weighted by the feature value (meaning features with higher values will have a larger effect). It points in the direction of steepest ascent, so to minimise the cost function, we want to move in the opposite direction:

- Positive gradient: the slope is upward (cost increasing), which occurs when the predicted probability > \(y_i\). We need to decrease \(\theta_j\).

- Negative gradient: the slope is downward (cost decreasing), which occurs when the predicted probability < \(y_i\). We need to increase \(\theta_j\).

- Large gradient (steep slope): the predicted probability is far from the actual (large error), so we need a large adjustment.

- Small gradient: the predicted probability is close to the actual label, not much adjustment needs to happen.

We can re-write the equation to do all the model parameters (θ) at once, producing a nx1 vector of partial derivatives (one for each feature \(\theta_j\)).

\[\nabla_\theta \ell(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left( \sigma(x_i \cdot \theta) - y_i \right) x_i\]First order methods

Gradient descent, and versions of it (Stochastic Gradient Descent, Stochastic Average Gradient), use only the first derivative (gradient) to optimise the coefficients.

Gradient Descent

For gradient descent, the parameters θ are updated iteratively in the direction of the negative gradient of the cost function. The update rule for each iteration k is:

\[\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k - \alpha \nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta_k)\]Where:

- \(\theta_k\) is the parameter vector at iteration k.

- \(\alpha\) is the learning rate, a tunable parameter that controls the step size (how much we adjust the parameters in each iteration). Too small, and convergence will be slow, but too large and it will bounce back and forth.

- \(\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta_k)\) is the vector of gradients, which we subtract from the current \(\theta\) (since we want to minimize the cost function, we move in the direction of the negative gradient).

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

Instead of using the entire data set to compute the gradient, this uses one random data point at a time to speed it up:

- Pick one random sample from the dataset (stochastic).

- Compute the gradient of the cost function with respect to this sample.

- Update the model parameters based on this gradient.

- Repeat this process for the entire dataset (one data point at a time) until convergence.

This is faster per iteration and less memory intensive, so good for large data sets. However, the updates can be noisy, causing it to take longer to converge (oscillating the minimum).

Stochastic Average Gradient (SAGA)

Stochastic Average Gradient (SAGA) is designed to make Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) converge faster. Like in SGD, it still picks one random sample to calculate the gradient. However, it stores the average of the gradients over time, using this average to update the parameters. This reduces the variance, making the updates less noisy and gradient estimates more accurate leading to faster convergence. It’s particularly efficient for sparse data sets, e.g. models with L1 regularisation.

Coordinate Descent (liblinear)

Unlike gradient descent which updates all the parameters at the same time, coordinate descent updates one parameter at a time while keeping the others fixed (i.e. it works through k iterations, applying the update rule to one \(\theta_j\), then moving on to the next one):

\[\theta_j^{k+1} = \theta_j^{k} - \alpha \frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_j}\]Where:

- \(\alpha\) is the learning rate

- \(\frac{\partial J(\theta)}{\partial \theta_j}\) is the partial derivative

It’s efficient for small data sets and supports regularisation, but other methods work better for large data.

Second Derivative

The second derivative captures the curvature of the function (how quickly the gradient is changing). This helps us understand where in the concave we are, so we can optimise the step size for faster convergence. We use what’s called a Hessian matrix to represent the second-order partial derivatives of the negative log-likelihood function with respect to each pair of parameters (i.e. it’s n by n):

\[H(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^{m} \sigma(x_i \cdot \theta) \left( 1 - \sigma(x_i \cdot \theta) \right) x_i x_i^T\]Where:

- \(x_i\) is the feature vector for the i-th observation.

- \(x_i x_i^T\) is the outer product of the feature vector with itself, forming a matrix (each element reflects how changes in one feature relate to changes in another feature for that specific observation).

The diagonal elements of the Hessian matrix reflect the curvature with respect to a single feature (\(\theta_j\), including the intercept). High values indicate large curvature (gradient is changing rapidly), and low values indicate flatter curvature (gradient is changing slowly). For example, a large positive value indicates it’s curving up rapidly (e.g. likely approaching the minimum), and we should take smaller steps to avoid overshooting. The off-diagonal captures the interactions (how the change in one feature affects the gradient of another), with a larger value indicating a higher correlation. This results in coordinated updates for correlated features. We take the inverse of the matrix to scale the parameter update (i.e. take a larger update when curvature is small to speed it up, and small when it’s large to avoid overshooting). While using the second derivative speeds up convergence, computing the inverse of the Hessian matrix makes it more computationally expensive.

Second order methods

Newton’s method uses both the gradient (first derivative) and the Hessian matrix (second derivative) of the cost function to update the model parameters more efficiently. The Hessian matrix is computationally expensive, so there are also methods that try approximate it like IRLS and BFGS.

Newton’s method

Using Newton’s method, the parameters θ are updated iteratively in the direction of the negative of the inverse of the Hessian matrix, scaled by the gradient of the cost function. The update rule for each iteration k is:

\[\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k - H^{-1}(\theta_k) \nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta_k)\]Where:

- \(\theta_k\) is the parameter vector at iteration k.

- \(H^{-1}(\theta_k)\) is the inverse of the Hessian matrix (second derivatives)

- \(\nabla_\theta \mathcal{L}(\theta_k)\) is the gradient of the cost function (first derivatives) and adjusts

The product of the inverse Hessian matrix and the gradient is subtracted from the current \(\theta\) to move in the direction of the negative gradient, but adjust the size of the step based on the curvature. This is what allows it to converge faster than the first order methods.

Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares (IRLS)

The IRLS algorithm can be viewed as a special case of Newton’s method (approximates it). It uses a diagonal weight matrix instead of the full Hessian, making it computationally more efficient. The update rule is:

\[\theta_{k+1} = \theta_k + (X^T W_k X)^{-1} X^T (y - \hat{p}_k)\]Where:

- \(\hat{p}_k\) is the vector of probabilities

- \(W_k = \text{diag}(\hat{p}_i (1 - \hat{p}_i))\) is a diagonal matrix which weights the observations based on how confident the model is about the prediction (i.e. diagonal is larger when p is closer to 0.5 and smaller when near 0 or 1).

This generally converges faster than the first order methods, and is more efficient than Newton’s method as it doesn’t need to compute the inverse Hessian matrix.

Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS)

BFGS is a quasi-Newton method that approximates the inverse Hessian matrix, making it computationally more efficient than standard Newton’s method. It starts with a guess (e.g. the identity matrix), and then builds up an approximation to the Hessian matrix based on the observed changes in gradients and parameters during the optimization process.

\[H_{k+1} = H_k + \frac{y_k y_k^T}{y_k^T s_k} - \frac{H_k s_k s_k^T H_k}{s_k^T H_k s_k}\]Where:

- \(y_k = \nabla f(\theta_{k+1}) - \nabla f(\theta_k)\) is the change in the gradient (from the last iteration)

- \(s_k = \theta_{k+1} - \theta_k\) is the change in the parameters

- \(H_k\) is the approximation of the inverse Hessian

For high dimensional problems, there’s L-BFGS (Limited-memory BFGS), which avoids storing the full Hessian approximation.

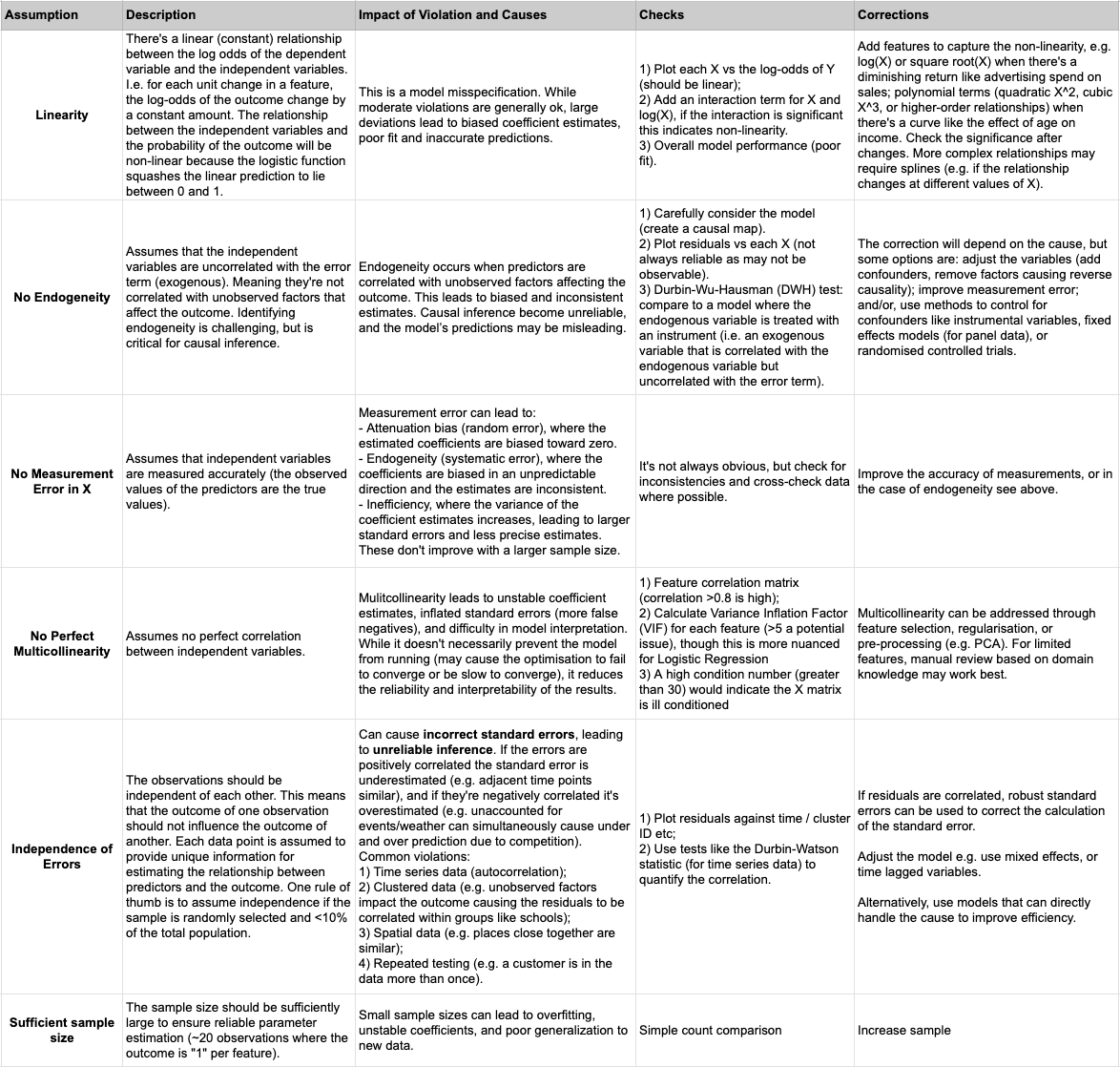

Assumptions

The key assumptions that must be met for logistic regression include: independence of errors, linearity in the log odds, no multicollinearity, no measurement error in X, no endogeneity (for causal inference), and a “large enough” sample to avoid overfitting (~20 observations per feature). While not an explicit assumption, logistic regression is sensitive to outliers and they can have a significant impact on the model’s performance and results. There are a number of parallels with the assumptions of linear regression, but also some key differences. Most notably, we don’t make the same assumptions about the error due to the binomial nature of the outcome variable (i.e. we don’t assume homoscedasticity, and normally distributed errors centered on 0). Rather than modeling the residuals as errors in the traditional sense, the logistic model focuses on estimating the log-odds of the outcome given the predictors, which can handle the non-normality and heteroscedasticity inherent in binary outcomes.

Exploratory Data Analysis

Some of the assumptions like linearity and multicollinearity can be checked by doing some pre-modelling analaysis of the data. Typically this would include: 1) reviewing the features that should be included (giving thought to potential confounders); 2) visualising the relationship between the log odds and each feature; and, 3) checking if features are highly correlated.

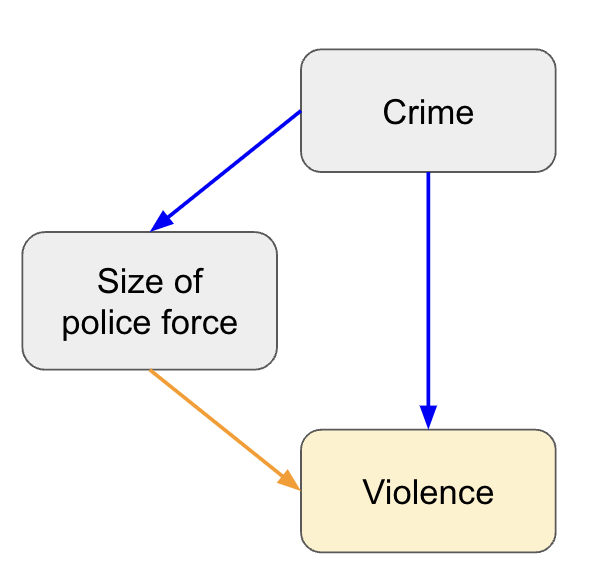

1. Causal map

This can be as simple as writing down the outcome, then adding the common factors (features) that might influence it, with lines and arrows to show the expected relationship. Next you can add unmeasured (or difficult to measure) factors that might influence either the outcome or features. This process helps you understand how much of the outcome you are likely to be able to explain, allows you to be explicit in your assumptions, and can help you with interpreting the results. Using a very simplified example, if you predicted the rates of violence based on the size of the police force, you may conclude they’re positively correlated (more police equals more violence) because you’re missing the confounder of crime rate (higher crime equals more police and more violence).

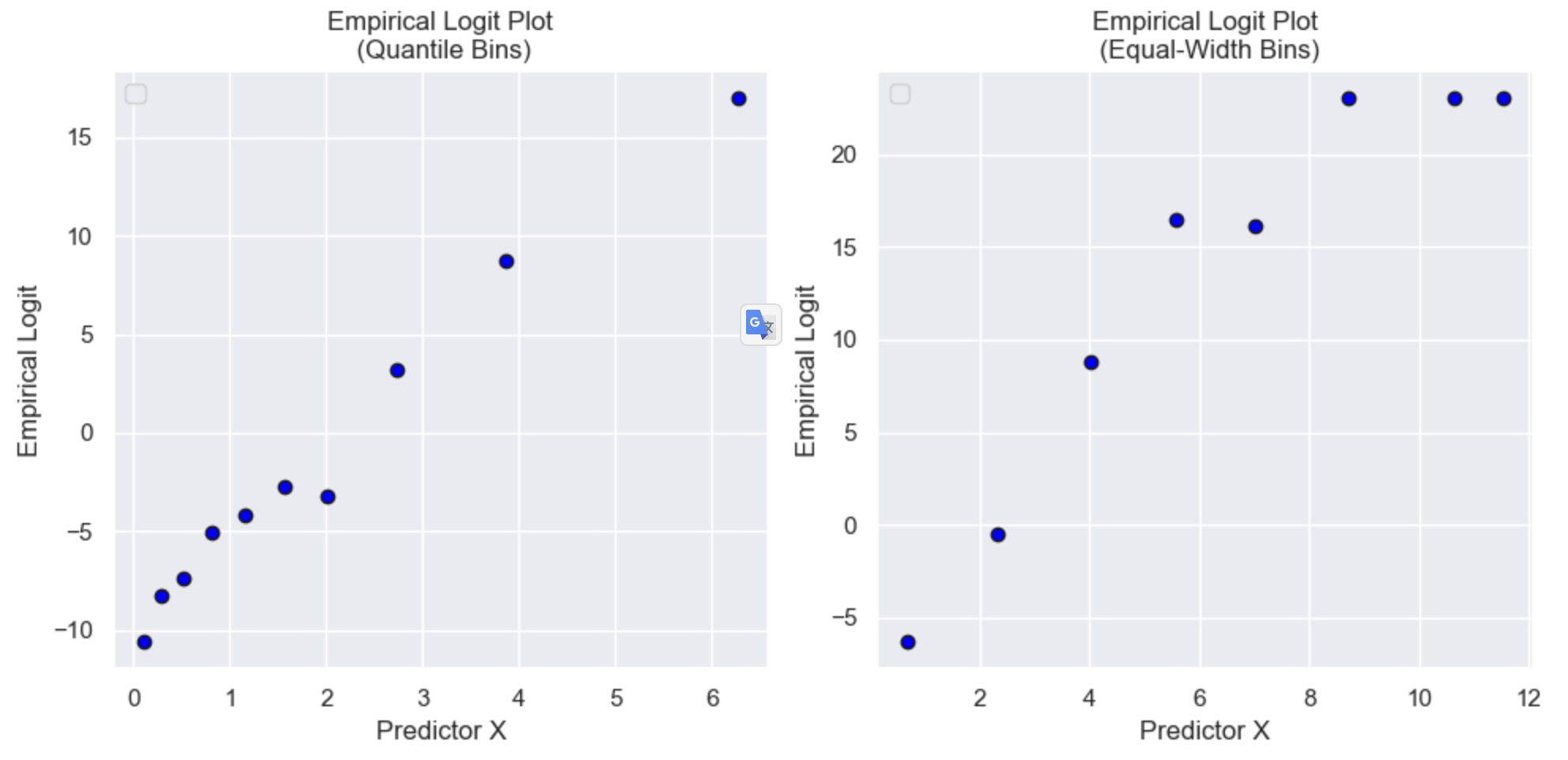

2. X vs Y plots

This is not as straightforward as linear regression where we can use simple scatterplots, as we are interested in the log odds of Y (which ranges from −∞ to +∞). One option is to break continuous features into bins, within each bin compute the average X and average Y, and then transform the average Y to log odds (\(\text{logit}(p) = \ln \left( \frac{p}{1 - p} \right)\), where p is the proportion of 1’s). This puts Y on a reasonable scale, but also reduces the influence of noise to focus on the broader trend. Different binning methods can also be tested depending on the distribution of X (e.g. equal sized bins for a skewed distribution).

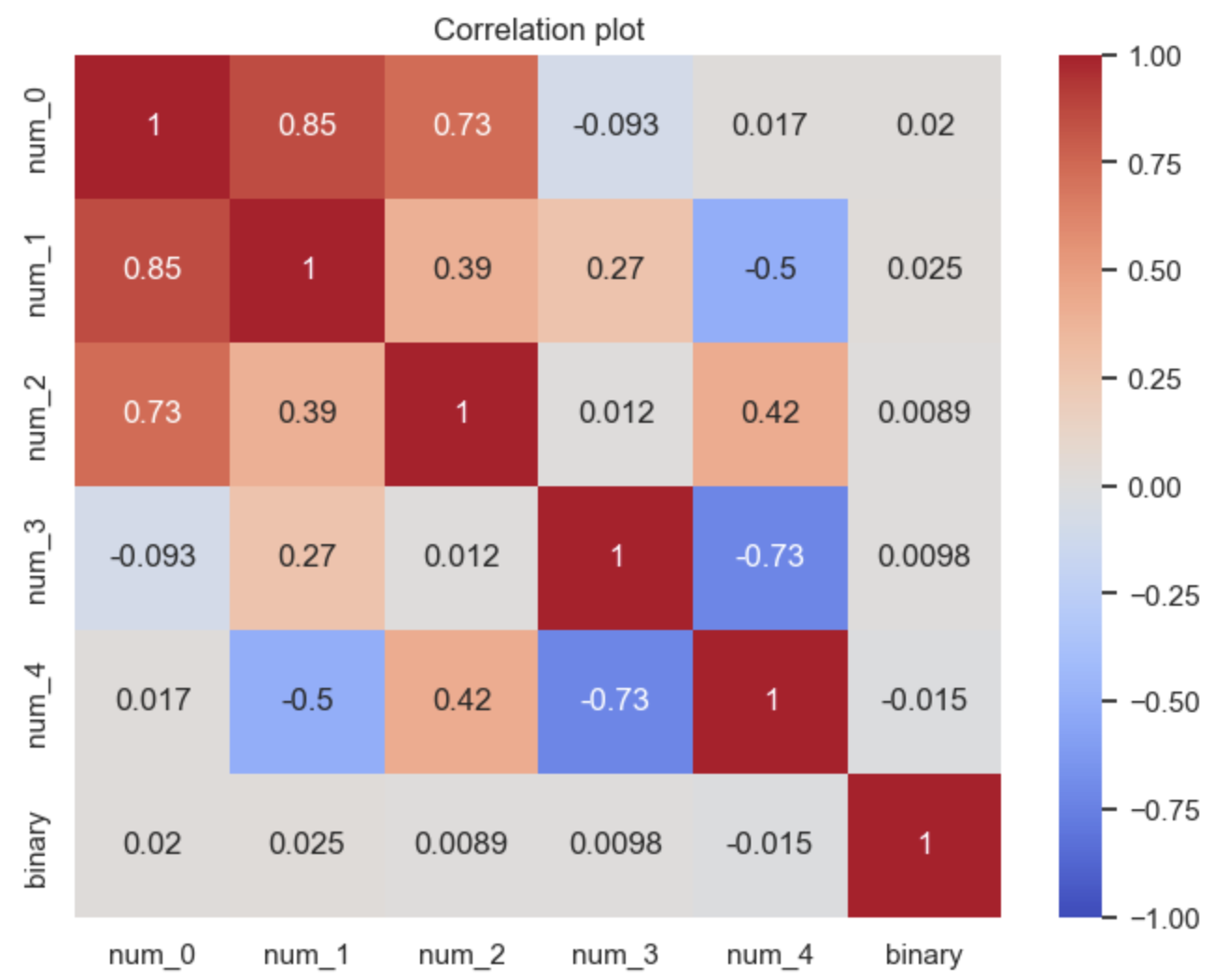

3. Correlation

The measure of correlation will depend on the feature type. For example, you could use:

- Numerical vs numerical: Pearson’s correlation

- Numerical vs binary: Point bi-serial correlation

- Numerical vs categorical: ANOVA

- Categorical vs categorical: Cramer’s V or Chi-squared

If you have a lot of features it can be useful to compute all these measures and then display them in a heatmap to quickly spot the highly correlated pairs, though you may need to scale some of the scores which are on different scales.

Evaluation

When evaluating the model, we want to assess whether we have a “good” model, meaning it fits the training data well, has good predictive accuracy (on unseen test data, i.e. doesn’t overfit), and doesn’t violate the assumptions. This section will cover the most common metrics and plots you would use to do this for logistic regression.

Splitting the data

Something to keep in mind is the bias variance tradeoff. Typically, the more you increase model complexity, the more you reduce the bias (error), but increase variance (the model doesn’t generalise to new data). This is the same thing as overfitting the training data. To avoid this, we split the data so that we can check the performance on both the training data and unseen test data. This can be a fixed split (e.g. 80% used for training, 20% held out for testing), or you can use k-fold cross validation (train on k-1 folds and test on the remaining, repeating k times). The benefit of the cross validation approach being that we can use all of the data for training (more efficient), and we’re less likely to overfit as we’re splitting multiple times and averaging over these to understand the performance. However, it’s more computationally expensive, so better for smaller data sets (k is typically 5-10, but stability and cost increase with k).

Overall fit

Below are the most common metrics for logistic regression. These can all be computed for the training and test data, but those focused on the model fit and comparison of models are typically only used on the training (e.g. AIC, BIC).

| Metric | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Deviance (log likelihood) | \(\text{D} = -2 \cdot \left(\log(\mathcal{L}(\hat{\theta})) - \log(\mathcal{L}(\theta_0))\right)\) | Measures the goodness of fit for the model by comparing the likelihood of the fitted model (\(\mathcal{L}(\hat{\theta})\)) to that of the null model (\(\mathcal{L}(\theta_0)\)). Lower values indicate a better-fitting model. If the deviance is close to the deviance of the null model, the model is not explaining much variation. Used in likelihood ratio tests for model comparison. |

| Pearson chi-square | \(\chi^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{(y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}{\hat{y}_i(1-\hat{y}_i)}\) | Measures the discrepancy between the observed (\(y_i\)) and expected (\(\hat{y}_i\)) frequencies for each data point. It is used to assess how well the model fits the data. A large value indicates a poor fit. A Pearson chi-square value greater than the degrees of freedom suggests overdispersion. |

| Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test | \(\chi^2 = \sum_{g=1}^{G} \frac{(O_g - E_g)^2}{E_g(1 - E_g)}\) | This test groups data into bins based on predicted probabilities, then compares the observed frequencies (\(O_g\)) to the expected frequencies (\(E_g\)) for each group. The statistic tests whether the observed data deviate significantly from the expected values. A significant p-value (typically < 0.05) suggests poor model fit. |

| AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) | \(\text{AIC} = 2k - 2\log(\mathcal{L}(\hat{\theta}))\) | A measure of model fit that also penalizes for the number of parameters (k) in the model. Lower AIC values indicate a better model. A model with a smaller AIC is considered better in terms of balance between fit and complexity. However, AIC should only be used for model comparison and not to assess a single model’s quality. |

| BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) | \(\text{BIC} = \log(n)k - 2\log(\mathcal{L}(\hat{\theta}))\) | Similar to AIC but with a stronger penalty for more parameters, where n is the sample size and k is the number of parameters. A lower BIC value indicates a better model. BIC tends to favor simpler models compared to AIC, especially as the sample size increases. |

| Pseudo-R-squared (McFadden’s) | \(R^2_{\text{McFadden}} = 1 - \frac{\log(\mathcal{L}(\hat{\theta}))}{\log(\mathcal{L}(\theta_0))}\) | Compares the log-likelihood of the fitted model with that of the null model (intercept-only). Values closer to 1 indicate a better-fitting model, while values close to 0 indicate a poor fit. A common rule of thumb: McFadden’s \(R^2\) values between 0.2 and 0.4 indicate a good fit, though values lower than this may still be acceptable depending on the application. |

| Pseudo-R-squared (Adjusted McFadden’s) | \(R^2_{\text{adj}} = 1 - \frac{(1 - R^2_{\text{McFadden}})(n - 1)}{n - p - 1}\) | Adjusts the McFadden’s pseudo-\(R^2\) for the number of predictors p and sample size n to account for overfitting. This version is useful when comparing models with different numbers of predictors. A higher value indicates better fit, but the adjustment makes it more conservative in penalizing complexity compared to the regular McFadden’s \(R^2\). |

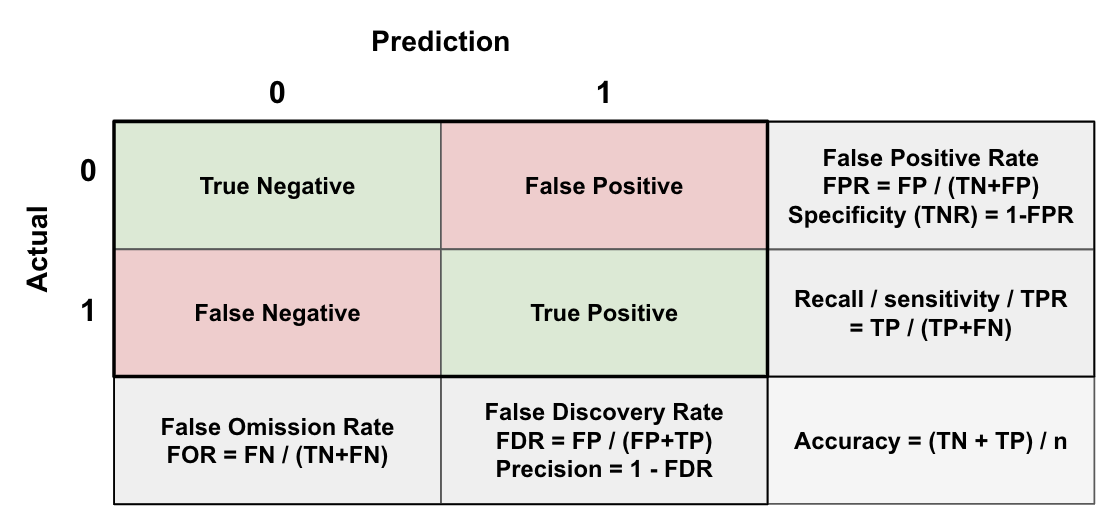

Classification performance

In addition to the overall model fit, it’s common to check the model’s ability to discriminate between the two classes (0 and 1). This is typically done for both the training and test data. To do this we set the decision threshold (e.g. 1 if p>=0.5, else 0), and then we can use standard classification metrics:

- Accuracy: % of observations that are correctly predicted. If the outcome is not 50/50 this can be misleading ((e.g. if 90% are 0 we can get 90% accuracy just by predicting all 0);

- Recall: % of the actual 1’s (positive class) that we correctly predicted as 1 (i.e. how many we catch);

- Precision: % of the predicted 1’s that are actually 1 (i.e. 1-precision is the % that are actually 0);

- F1 score: Weighted average of recall and precision, \(\text{F1} = 2 \cdot \frac{\text{Precision} \cdot \text{Recall}}{\text{Precision} + \text{Recall}}\);

These can be conveniently calculated and displayed using just a cross tabulation of the predicted and actual labels (i.e. a confusion matrix):

Precision and Recall are often inversely related: as you increase recall (by lowering the threshold to classify positives), precision might decrease, and vice versa. This happens because decreasing the threshold increases the number of true positives, but also increases the number of false positives. Depending on your use case you can adjust the probability threshold to select a trade-off that’s suitable (e.g. if the cost of a False Negative is high and the intervention cost is low, you might be ok with a lower precision, i.e. more False Positives).

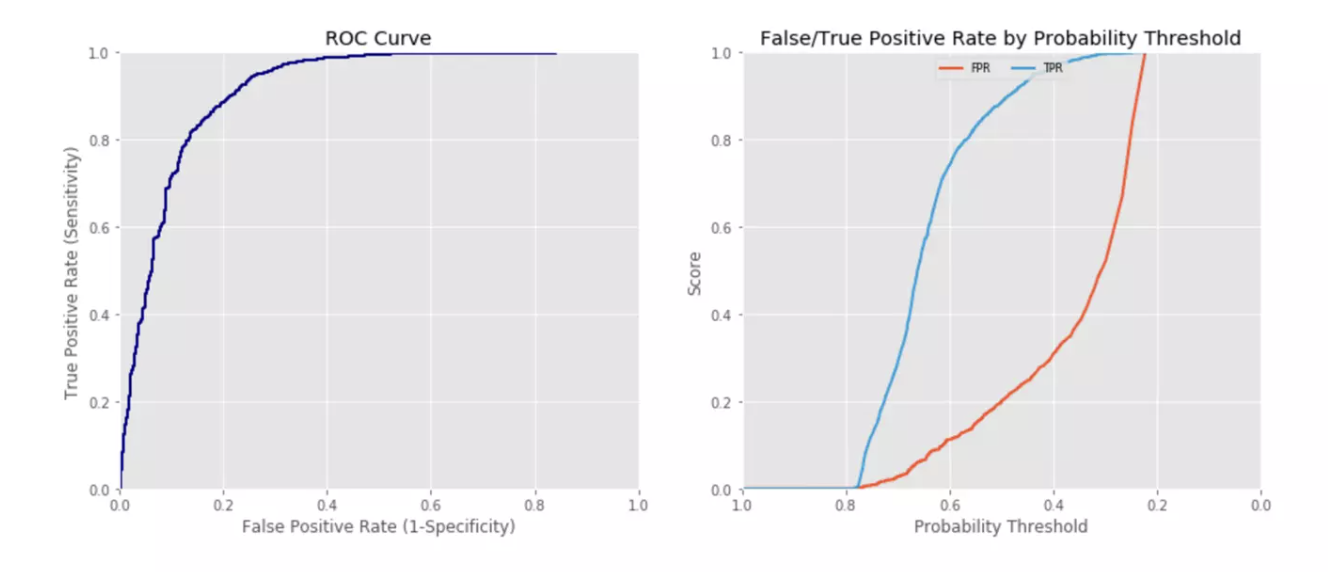

ROC

One way of visualising the trade-off it to plot the Receiver Operator Curve (ROC) which shows the False Positive Rate vs the True Positive Rate (Recall) at different probability thresholds (each point on the curve represents a different threshold):

We can quantify the curve using metrics:

- ROC AUC: The likelihood that a randomly chosen positive instance will have a higher predicted probability than a randomly chosen negative instance. Ranges from 0-1, where: 1=perfect; 0.5=random (diagonal line); and, <0.5 means worse than random (predictions reversed). For example, 0.8 means that 80% of the time it will rank a randomly chosen positive example higher than a randomly chosen negative example). A model with a high AUC has a good ability to distinguish between positive and negative classes, which indirectly suggests better precision and recall at various thresholds.

- Gini coefficient (\(\text{Gini} = 2 \times \text{AUC} - 1\)): This can be thought of as a re-scaled version of AUC that makes it immediately interpretable as a % improvement/worsening of the model’s ability to separate classes. It ranges from -1 to 1, where 0 is equivelant to an AUC of 0.5 (random). E.g. 0.7 means the model performs at 70% of perfect discriminatory power.

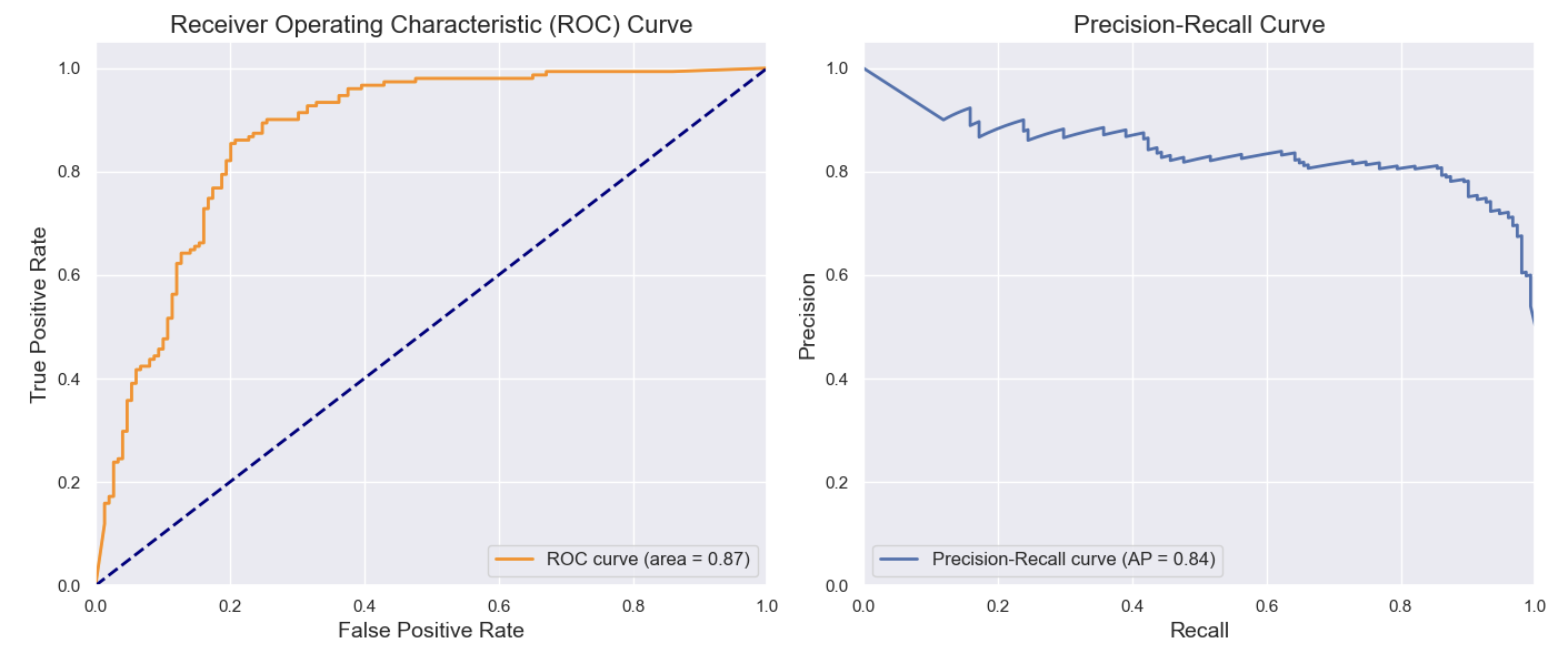

Precision-Recall Curve

However, precision and recall are more sensitive to imbalanced datasets than the ROC-AUC. For imbalanced datasets, precision-recall curves and metrics like F1 score may be more informative, whereas the ROC curve might appear overly optimistic.

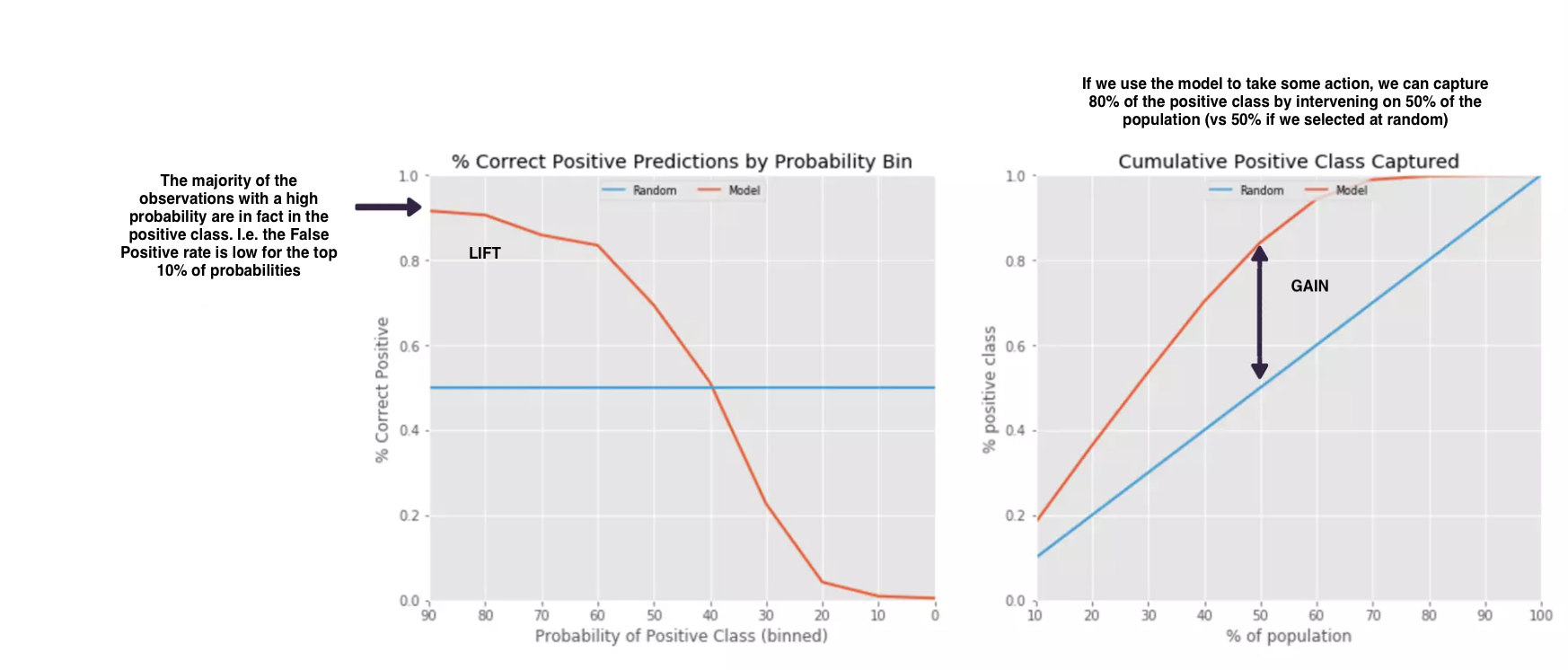

Lift/Gain:

Another way to visualise how good the model is at discriminating the positive class is to plot the lift and cumulative gain. Lift measures the improvement a model has over random guessing. It shows how much better a model is at predicting positive cases in the top n% of the data compared to randomly selecting n% of the data. Meanwhile, gain measures the cumulative number of positive cases that the model is able to correctly identify when we rank all instances in the dataset by predicted probability. It provides a way to see how much better the model is at identifying positive cases compared to random selection.

These are useful when the outcome is imbalanced and you’re primarily interested in the minority class (e.g. fraud), as you can get a clear picture of the effectiveness.

Residuals

Looking at the performance at a more granular level, we want to understand which observations the model is doing well with and which it is not. To do this we need to define a residual. Residuals represent the difference between the observed values and the values predicted by the model. In a linear regression model, this is just the difference between Y actual and Y predicted (the error in predicting the continuous outcome). However, in logistic regression we model the probability of Y equalling 1 (\(P(Y=1 \mid X)\)), rather than the outcome directly (which is 0 or 1). Therefore, the residuals behave a bit differently, and we have two common methods of defining them: Pearson and Deviance. Pearson residuals give a measure of the absolute deviation from the expected outcome in terms of the predicted standard deviation, whereas deviance residuals give a measure of the log-likelihood ratio discrepancy between the observed and expected outcomes. They can provide complementary insights, so both are often computed and plotted to check for outliers an potentially influential observations.

Deviance Residuals

Deviance residuals measures the contribution of each observation to the overall deviance (a goodness-of-fit statistic), and is closely related to the likelihood function. They are useful for detecting model misfit, influential observations, and outliers.

\[d_i = \text{sign}(y_i - \hat{p}_i) \sqrt{-2 \ln \left( \frac{L(y_i | \hat{p}_i)}{L(1 - y_i | \hat{p}_i)} \right)}\]Where:

- \(L(y_i \mid \hat{p}_i)\) is the likelihood of observing \(y_i\) (the actual binary outcome), given the predicted probability \(\hat{p}_i\). I.e. it’s the likelihood of a single observation (\(L(y_i \mid \hat{p}_i) = \hat{p}_i^{y_i} (1 - \hat{p}_i)^{1 - y_i}\)), which becomes \(\hat{p}_i\) if \(y_i=1\) and \((1-\hat{p}_i)\) if \(y_i=0\). We covered this earlier as a building step to the log likelihood (which sums these individual likelihoods).

- The ratio \(\left( \frac{L(y_i \mid \hat{p}_i)}{L(1 - y_i \mid \hat{p}_i)} \right)\) compares the likelihood of the observed value (\(y_i\)) with the likelihood of the opposite (\(1 - y_i\)). We take the log (ln) to put it in a scale comparable with the model.

- The -2 multiplication standardises the ratio to follow a chi-square distribution for easier statistical testing and inference.

- The sign term captures the direction of the difference, ensuring the residual takes the correct sign based on whether the event was observed or not (i.e. if \(y_i=1\) and \(p_i>0.5\) OR \(y_i=0\) and \(p_i<0.5\), the residual will be positive).

Compared to Pearson residuals they’re more sensitive to extreme cases, as the logarithmic function in the formula exaggerates errors when the predicted probabilities are far from the observed outcomes. The rule of thumb for an outlier is an absolute value greater than 2, which comes from the idea that this corresponds to roughly 2 standard deviations from the mean. Deviance residuals reflect how well the model fits the data in terms of the log-likelihood, making them useful for comparing models. The overall goodness of fit metric Deviance is just the sum of the squared deviance residuals.

Pearson Residuals

Pearson residuals offer a different perspective. They’re based on the chi-square statistic (the sum of squared residuals divided by the predicted variance), and are useful for identifying observations that are poorly fit by the model.

\[r_i = \frac{y_i - \hat{p}_i}{\sqrt{\hat{p}_i(1 - \hat{p}_i)}}\]Where:

- The denominator is the standard error of \(p_i\) (the square root of the variance of the Bernoulli distribution).

If the logistic regression model is well-calibrated, the Pearson residuals should follow a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1. This gives the rule of thumb that absolute values of \(r_i\) greater than 2 could be an outlier, or observation the model is not good at predicting. To limit it to extreme cases, a threshold of 3 is also common. Pearson residuals provide a standardised and more stable measure of residuals compared to Deviance, and are useful for identifying observations where the model performs poorly. However, this also means they tend to reduce the impact of extreme deviations compared to Deviance as they’re scaled down by the denominator.

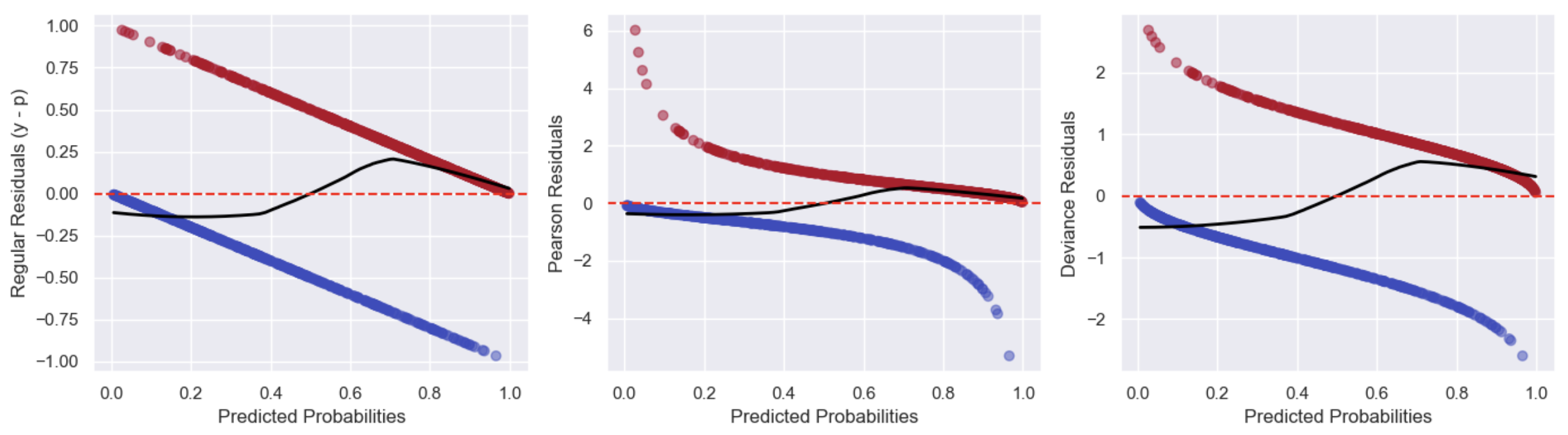

Assessing residuals

Standard residual plots (e.g. residuals vs fitted values, and residuals vs Xs) are hard to judge. If the actual outcome is 0, then the probability will be more, and residuals have to be negative (blue) and if the actual outcome is 1, we underestimate, and residuals have to be positive (red). Using Pearson/Deviance residuals doesn’t help here much. We can add the LOWESS (Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing) curve to try detect the pattern (the closer it is to flat with a 0 intercept the better):

Further, some heteroscedasticity (non constant variance) is expected in the residual plots as the variance of the Pearson residuals is a function of the predicted probability: \(\text{Var}(Y_i) = \hat{p}_i (1 - \hat{p}_i)\), meaning it will be largest near \(\hat{p}_i=0.5\) and smallest close to 0 and 1. Deviance residuals have a similar pattern due to the likelihood of observing the data being larger (and the residual smaller) when the predicted probability is closer to 0 or 1. However, non-random patterns (e.g. a U shape or clusters, outliers) would still indicate a potential issue.

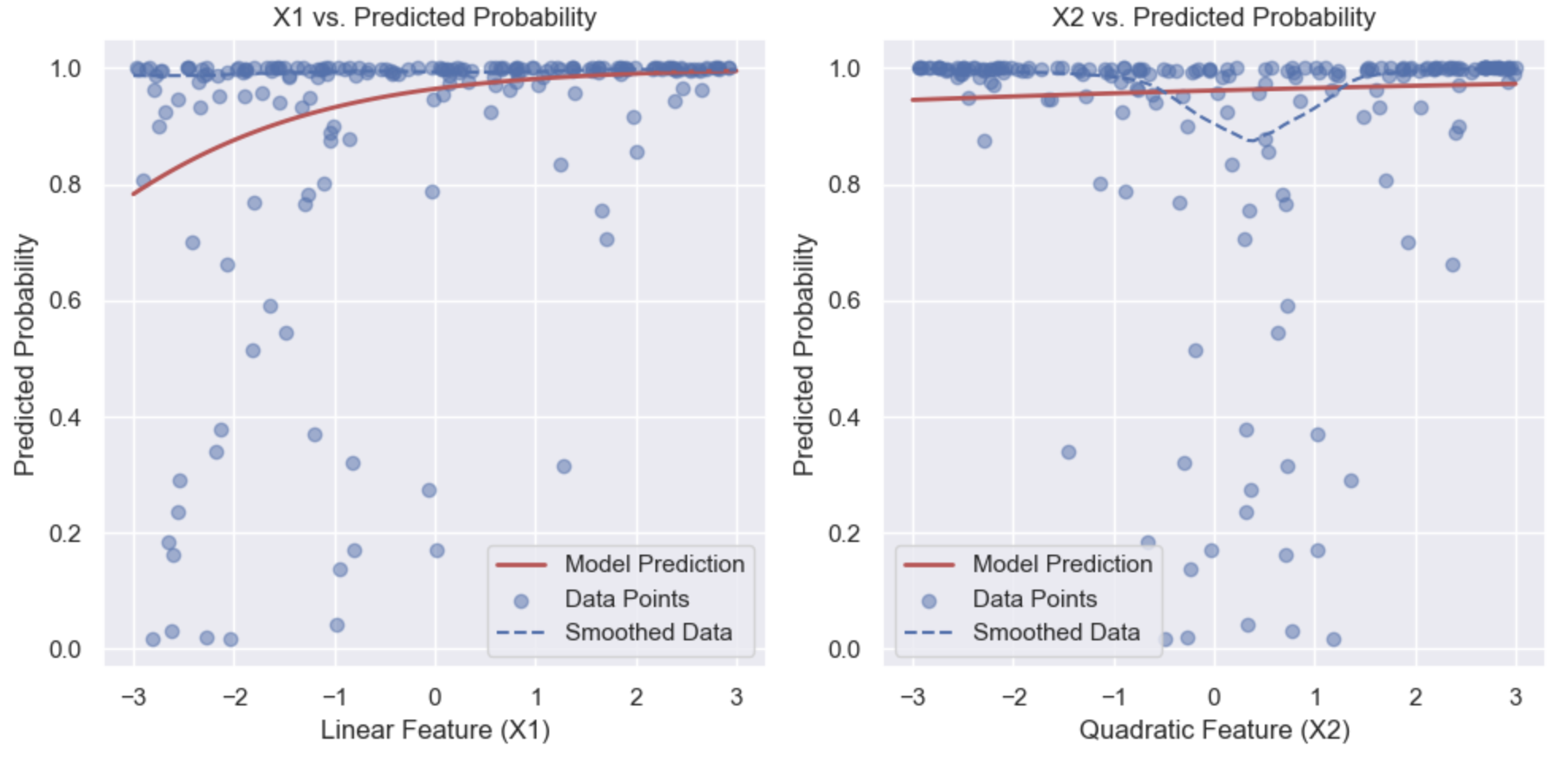

Marginal Model Plot

This visualises the relationship between a single feature (x) and the predicted probabilities (y) in a logistic regression model. By varying the feature from its minimum to maximum value while holding other features constant (typically at their mean or another chosen value), you calculate the predicted probabilities and plot them against the feature values. This shows how the predicted probability changes with the feature, allowing you to assess the marginal effect of that feature on the outcome. The plot helps evaluate whether the relationship is linear or not.

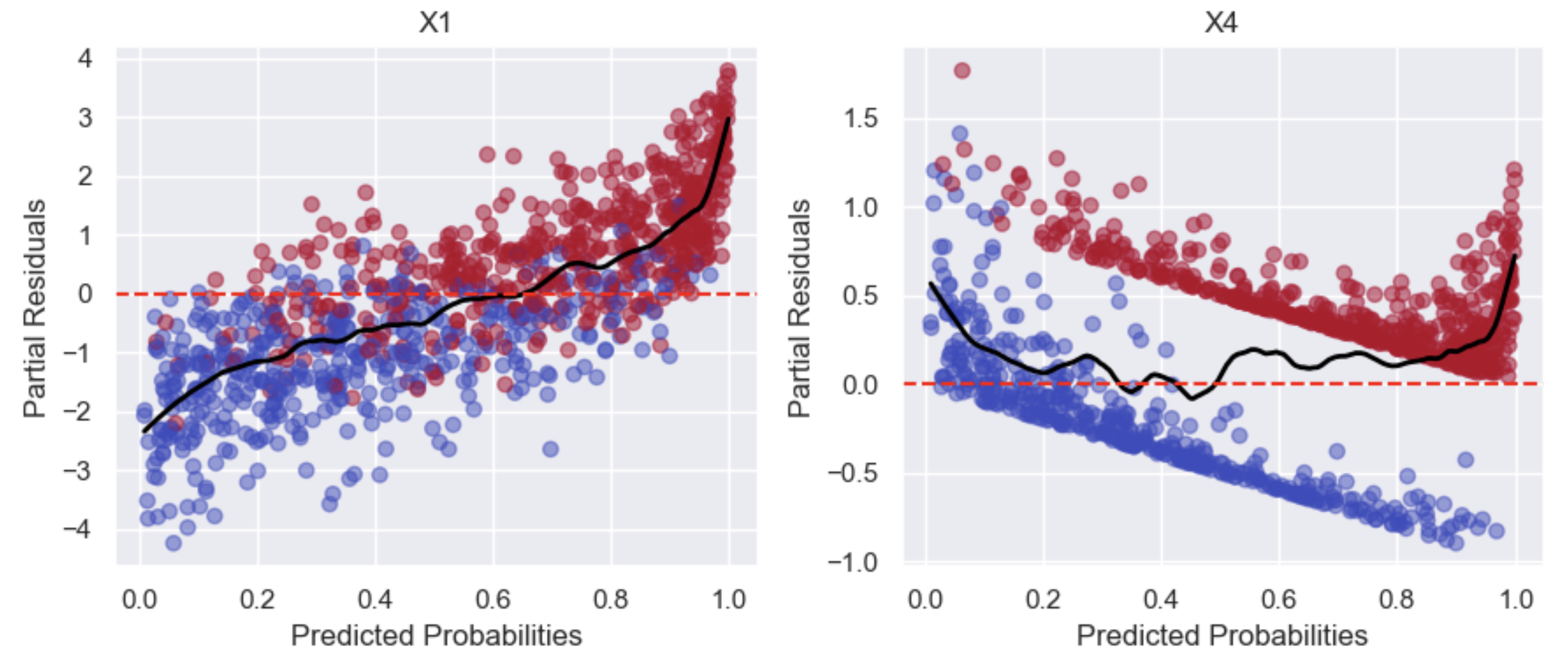

Partial Residual Plot

This is used to evaluate whether the relationship between each feature and the outcome is linear in the log-odds. Partial residuals are trying to isolate the effect of X1 on the outcome, while holding the influence of all other features constant. This is done by taking the residual (unexplained part) and adding back the effect of \(\beta_1 X_1\):

\[\text{Partial Residuals} = Y - \hat{Y} + \beta_1 X_1\]Where:

- Y is the observed outcome

- \(\hat{Y}\) is the predicted probability

- \(Y - \hat{Y}\) is the residual, or the unexplained portion of the outcome

- \(\beta_1 X_1\) is the linear contribution of the feature to the model

Adding \(\beta_1 X_1\) back to the residuals allows us to examine how X1 is associated with the outcome in the presence of other features, and to check if its relationship with the outcome is linear or not. In the example below, X1 looks linear but X4 does not:

Outliers / influential observations

Outliers can be identified during the residual diagnostics, but can be more formally defined using Cook’s distance or leverage. Given these are about the model fit, we calculate them only for the training data:

- Leverage (0-1): a measure of how far an observation’s features are from the mean of all the feature values. This identifies how much influence an individual data point has on the fitted model. Higher leverage indicates that the data point is far from the mean of the other feature values and thus has more potential influence on the model (rule of thumb for high: $$\frac{2p}{n}, where p is the number of features and n is the number of observations). If they’re also outliers, then they can heavily influence the model coefficients.

- Cook’s distance: Quantifies how much impact that point has on the final model output. This is possible to compute but more complicated for Logistic Regression as the variance and residuals are not constant and depend on the predicted probabilities: \(D_i = \frac{(y_i - \hat{p}_i)^2}{p \cdot \hat{\sigma}^2} \cdot \frac{h_i}{(1 - h_i)^2}\)

It’s important to understand the cause of outliers before choosing a method to handle them. If they’re due to data entry errors, they can be removed or corrected. For random outliers, consider capping or winsorizing values at specific percentiles (e.g., 5th and 95th), but this can introduce bias or data loss if done incorrectly. Replacing outliers with the mean or median is another option, though it can also skew results if not representative of the data. If outliers reflect distinct groups (e.g, travel agents behaving differently from regular customers), consider modeling them separately or using interaction terms. For random outliers, robust regression methods can reduce their impact without altering the data.

Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity occurs when one feature is highly correlated with another, which can lead to unreliable estimates of the coefficients and inflated standard errors. Two commonly used diagnostics for identifying highly correlated features are the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and the condition number.

- Condition number: the ratio of the largest eigenvalue to the smallest eigenvalue of the feature matrix X. It quantifies the sensitivity of the model’s solution to small changes in the data, which reflects potential issues with multicollinearity. A value >30 would be considered high, indicating high multicollinearity.

- VIF: Each predictor is regressed against the others using linear regression to compute an R^2 and corresponding VIF (\(VIF_i = \frac{1}{1 - R^2_i}\)). If VIF values are high (typically greater than 5 or 10), it suggests significant multicollinearity.

If multicollinearity is an issue, a common solution is to reduce the feature set by: manually removing one from each pair; combining features (e.g, with PCA); or using regularisation.

Iterating on the model

Based on the evaluation, you can test a number of adjustments to the model to see if it improves the performance. For example, considering terms for interactions or non-linearities, and using regularisation or other methods to correct for multicollinearity.

Adding terms

Adding new features that are predictive of the outcome can improve the model’s accuracy, but also the precision of the coefficient estimates (i.e. smaller confidence intervals). However, adding too many features that have a weak or no effect on the outcome leads to overfitting. If they’re highly correlated (multicollinearity), it can also destabilise the coefficient estimates and increase their variance. An example of this is adding features that are predictive of another feature, but not the outcome. It can lead to multicollinearity, or reduce the variance of the feature (which is harmful). The other type of features you might add are variations of the existing, such as: polynomials (i.e. X^n to capture non-linearity); and, interactions (when the effect of one feature might depend on the value of a second feature). As with the above, adding too many can lead to overfitting. This is where the next section on feature selection is useful.

Feature selection

You will typically start by selecting all the features you believe are important based on theory, prior knowledge, or existing literature. However, if you suspect multicollinearity or redundancy, you can also use feature selection methods:

- Forward Selection: Start with no predictors and iteratively add the most significant variable based on a chosen criterion (e.g. p-value or AIC), assessing whether each new variable improves the model.

- Backward Elimination: Start with all candidate predictors, and iteratively remove the least significant variable (based on a chosen criterion) until all remaining variables are significant or meet the desired criteria.

- Stepwise Selection: A combination of forward and backward steps where variables can be added or removed at each stage, depending on whether they improve the model’s fit.

Each model iteration is evaluated based on a chosen statistic (e.g., AIC, BIC, likelihood ratio test) to decide which variables remain in the model. The main downside of these is that there may not be good reasons for the choice of one feature over another, with implications on the interpretation of the model.

Regularisation

An alternative to the iterative feature selection methods is regularisation, which adds a penalty term to the loss function based on the coefficients to minimise the magnitude of the coefficients at the same time as maximising the log likelihood. This prevents overfitting by discouraging the model from assigning too much importance to any particular feature, but at the cost of higher bias (i.e. it reduces variance to improve test performance, but worsens training performance). Feature scaling (typically standardisation) is essential to avoid features with a larger range dominating the penalty term during regularisation. There are 3 main methods of regularisation:

1) Lasso (L1) adds a penalty proportional to the absolute value of the coefficients (some go to exactly 0). This is performing feature selection, but does bias the remaining coefficients (they’re shrunk). For interpretation purposes you might use it to select the features, but then re-fit a non-regularised model.

\[J(\theta) = -\frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[ y^{(i)} \log(h_{\theta}(x^{(i)})) + (1 - y^{(i)}) \log(1 - h_{\theta}(x^{(i)})) \right] + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{n} |\theta_j|\]2) Ridge (L2) adds a penalty proportional to the square of the coefficients (shrinks all, but not to 0):

\[J(\theta) = -\frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[ y^{(i)} \log(h_{\theta}(x^{(i)})) + (1 - y^{(i)}) \log(1 - h_{\theta}(x^{(i)})) \right] + \frac{\lambda}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \theta_j^2\]3) Elastic Net combines L1 and L2, with an additional parameter (alpha) added to control the mix. This method can be useful for correlated features. For example, if two features are highly correlated, the L1 term will push both coefficients towards zero if both are irrelevant, but the L2 term ensures that they are shrunk together. If both are important, the model will keep them but shrink their coefficients. In this way it handles groups of features better, as correlated features are more likely to be selected or discarded together, rather than arbitrarily.:

\[J(\theta) = -\frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} \left[ y^{(i)} \log(h_{\theta}(x^{(i)})) + (1 - y^{(i)}) \log(1 - h_{\theta}(x^{(i)})) \right] + \lambda \left( \alpha \sum_{j=1}^{n} |\theta_j| + \frac{1 - \alpha}{2} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \theta_j^2 \right)\]Where:

- \(\lambda\) is the regularisation parameter (lambda)

- \(\beta_j\) are the feature coefficients

- p is the number of features

- \(\alpha\) is the mix of Lasso and Ridge (1 would be Lasso only, 0 would be Ridge only)

The strength of the regularisation in all three methods is controlled by lambda (\(\lambda\)). Close to 0 (e.g. 0.01) there will be minimal regularisation (coefficients similar to without), around 1-5 there will be some shrinkage of the coefficients, and at large values (e.g. 10-100) there will be a lot of shrinkage and possibly all 0’s in the case of Lasso. Usually the value would be selected based on a grid search (test a set of values e.g. 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10), potentially with cross-validation (to ensure it generalises well).

Inference

When interpreting the coefficients of logistic regression, we often have causal questions in mind (e.g., how does feature X influence outcome Y?). However, in most cases, logistic regression reveals associations rather than causal relationships. While causal estimates can be obtained (e.g. if the data is from a randomised experiment), using observational data makes it challenging to confirm that all confounders have been accounted for. Despite this, logistic regression remains a valuable tool for generating hypotheses that can be further tested with other methods. If the primary goal is prediction, the coefficients may be less important. Nonetheless, understanding and explaining the predictions is still useful, and in some cases, necessary even in predictive contexts.

Coefficients

In logistic regression, the coefficients indicate how much the log-odds of the outcome are expected to change for a one-unit increase in the feature, holding all other features constant. Exponentiating the coefficients converts them into odds ratios, which are often easier to interpret. When the log-odds change linearly with the feature, the odds change multiplicatively, allowing us to interpret them as percentage changes in the odds. Converting directly to probabilities is possible, but the relationship is non-linear due to the sigmoid function.

An important nuance is that, unlike linear regression, the magnitude of logistic regression coefficients can change depending on which other covariates are included, even if they are not confounders. In linear regression, adding covariates typically reduces the standard error of the coefficient and may adjust the coefficient slightly if there is confounding, but the scale of the coefficient itself does not stretch due to residual variance in the same way.

Logistic regression models an underlying latent continuous propensity to experience the event, which is squashed through the logistic function. Adding covariates explains more of this latent variation, reducing the residual variation. To produce the same absolute change in probability on the 0–1 scale, the coefficient for a given variable must increase. To put it more simply, the probability change on the 0-1 scale is what you observe in the data. The log-odds coefficient is a scale-dependent measure of that change. When residual variation shrinks, the same probability difference corresponds to a larger coefficient. This does not imply the coefficient is closer to the true causal effect. This behaviour is not bias in the classical sense, but it does mean that odds ratios are sensitive to model specification and should be interpreted with caution, particularly in causal inference settings.

Let’s walk through some examples now. We fit the logistic model:

\[\log\left( \frac{P(Y = 1)}{1 - P(Y = 1)} \right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_1 + \beta_2 X_2 + \dots + \beta_n X_n\]The sign and magnitude of the coefficients tell us the direction of the effect and the size of the impact (+ means log odds increases with the feature; - means it decreases; and, the higher the magnitude the larger the effect). Then we can convert each coefficient from the log odds to odds (the multiplicative change in the odds of the outcome for a one-unit increase in \(X_i\)):

\[\text{Odds Ratio} = e^{\beta_j}\]- If \(e^{\beta_j} > 1\), the odds of the event occurring increase as \(X_i\) increases

- If \(e^{\beta_j} < 1\), the odds of the event occurring decrease as \(X_i\) increases

- If \(e^{\beta_j} = 1\), the feature has no effect on the odds of the event

Example:

Let’s say we want to predict whether a customer will convert based on their age, income, and loyalty status:

\[\log\left( \frac{P(\text{buy})}{1 - P(\text{buy})} \right) = -2 - 0.1 \cdot \text{age} + 0.03 \cdot \text{income} + 0.1 \cdot \text{loyalty}\]- Intercept (\(\beta_0\)): represents the log odds of buying when age and income are 0, and they’re not in the loyalty program (no meaningful interpretation given age=0 is unrealistic).

- Age: A 1 year increase in age (holding income constant) decreases the log-odds of buying by 0.1. If we exponentiate the coefficient (\(e^-0.1≈0.905\)), this suggests the odds of buying decrease by 9.5% (1-0.905) for every additional year of age.

- Income: A 1 unit increase in income (holding age constant) increases the log-odds by 0.03. Exponentiating this coefficient (\(e^0.03≈1.031\)), the odds of buying the product increase by 3.1% for each additional unit of income.

- Loyalty (0/1): If the customer is part of the loyalty program (1), this increases the log-odds of buying by 0.1. If we exponentiate the coefficient (\(e^0.1≈1.105\)), this suggests the odds of buying increase by 10.5%.

Other feature types:

- Log transformed: The effect is interpreted in terms of a percentage change in X rather than a unit change. E.g. a 1% increase in log(X1) leads to a % change in the odds.

- Polynomial: The effect of a feature depends on the value of the feature itself. You need to consider both the linear and polynomial coefficients and calculate the combined effect at different values of the feature.

- Interactions: A positive coefficient suggests the combined effect of both features is greater than the sum of their individual effects, while a negative coefficient suggests a weaker combined effect. Again, you would need to calculate the marginal effects for specific values of the features to fully understand how the interaction works.

Feature Importance

When using the magnitude of the coefficients to comment on the importance of a feature, make sure the features have been standardised so they have comparable scales. Also keep in mind they may be biased by multicollinearity and/or missing confounders, so it’s important to consider the results in the context of your model. That said, this is still a useful way for generating hypotheses about factors that are important for the outcome.

Standard errors

The coefficient estimates are based on one sample, so like with all sample statistics we want to know how much these estimates might vary from sample to sample. The standard error is exactly this, it gives us a measure of the uncertainty of the estimate. This is then used to construct confidence intervals and do significance tests. The larger the standard error, the higher the uncertainty, and the wider the confidence intervals. The standard errors of the coefficients in logistic regression are derived from the inverse of the Fisher Information matrix (or equivalently, the Hessian of the log-likelihood function).

Hessian Matrix (covered above under optimisation): represents the second-order partial derivatives of the negative log-likelihood function with respect to each pair of parameters \(\beta_j\) and \(\beta_k\) (i.e. it’s n by n).

\[H_{jk} = \frac{\partial^2 \ell(\beta)}{\partial \beta_j \partial \beta_k} = -\sum_{i=1}^n p_i (1 - p_i) X_{ij} X_{ik}\]The Fisher Information matrix is the negative of the Hessian.

\[I(\beta) = -H = \sum_{i=1}^{n} p_i (1 - p_i) X_i X_i^T\]It gives us a measure of how much information we have about each feature, based on the curvature of the log-likelihood function (the greater the information, the more precise our estimates of the coefficients will be). A larger value indicates small changes in the coefficient will have a large effect on the log likelihood and thus we have higher confidence in the estimates (lower variance).

The Standard Errors are then:

\[\text{SE}(\hat{\beta_j}) = \sqrt{\left( I(\beta)^{-1} \right)_{jj}}\]Where:

- \(I(\beta)^{-1}\) (inverse of the Fisher Information matrix) is the variance covariance matrix. The larger the Fisher Information, the smaller the variance (i.e. the more confident we are in our estimates).

- \(\left( I(\beta)^{-1} \right)_{jj}\) is the \(j-th\) diagonal element of the inverse of the Fisher Information matrix, and it represents the variance of \(\hat{\beta_j}\).

Robust standard errors

In linear regression, heteroskedasticity doesn’t lead to bias in coefficient estimates, only inefficiency. Robust standard errors adjust the variance-covariance matrix to account for heteroskedasticity, allowing us to still make valid inferences with consistent standard errors. In logistic regression it’s slightly more nuanced as we inherently expect heteroskedasticity due to the binary nature of the outcome variable (i.e. the variance of the errors depends on the predicted probability). This heteroskedasticity is accounted for in the model and not a problem. Other sources of heteroskedasticity are possible, but are typically related to model misspecification (e.g. omitted variables, missing interactions, wrong functional form), which leads to biased estimates (in both linear and logistic regression). Robust standard errors do not correct biased coefficient estimates, only the variance. Therefore, they are not very useful for this issue as it’s a correct standard error for an incorrect estimate. Using them might mislead you into thinking your results are more reliable than they actually are. It is better to address these issues directly (e.g. by adding the missing variables, transforming the predictors, or using more appropriate model forms).

Confidence Intervals

The calculations for the confidence intervals in logistic regression are similar to those in linear regression once we have the standard error. Recall, a confidence interval quantifies the uncertainty of a sample estimate (in this case \(\hat{\beta}_j\)), by giving us a range of values around the estimate that “generally” contains the true population value. Like any sample estimate, it’s unlikely that our coefficient is exactly equal to the true value. If we repeatedly sampled, we would get a distribution of coefficients around the true value (a sampling distribution), which, with a large enough sample size, converges to a normal distribution due to the properties of Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). In logistic regression, we typically use the Wald test to calculate significance, which uses z-scores. These are standardised (mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1), so when we select the critical z value, we are deciding how many standard errors we need to get x% coverage of the samples. Or in other words, how many standard errors will ensure that x% of samples contain the true value.

\[\hat{\beta}_j \pm z_{\frac{\alpha}{2}} \cdot \text{SE}(\hat{\beta}_j)\]Where:

- \(\hat{\beta}_j\) is the estimated coefficient for feature j

- \(z_{\frac{\alpha}{2}}\) is the critical z-value for the desired confidence level

- \(\text{SE}(\hat{\beta}_j)\) is the standard error, as calculated in the above section

To determine the critical value, we have to decide the confidence level (1-alpha). Typically in a business context the confidence is set at 95% (alpa=0.05) or 90% (alpha=0.1). The higher the confidence required, the wider the confidence interval will be to increase the chances of capturing the population value. Noting, the actual value may or may not be in the range for our given sample. Coming back to the sampling distribution (distribution of coefficient estimates across multiple samples), if we placed the resulting distance around each estimate we would see that 95% of the time (for alpha=0.05) the true value is within the interval. The other 5% of the time, we have a particularly high or low estimate (by chance) and miss the actual value. You can read more on confidence intervals here.

Interpretation

For logistic regression recall the coefficients represent a change in the log odds of the outcome being 1, but we typically exponentiate these coefficients to get the odds ratio which is more interpretable. If we exponentiate the coefficient then we should do the same to the upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval to get a confidence interval around the odds.

Hypothesis Tests

As we covered above, we’re estimating these coefficients based on just one sample. It’s possible that even if there is no relationship between feature j and the outcome y, we get a non-zero coefficient in our model. Hypothesis testing tells us how often we would expect to see a coefficient as large as that observed (or larger), when there’s actually no effect. If it’s uncommon, then we conclude there is likely a real effect. To determine if the effect of feature j on the outcome is statistically significant we use a Wald test, and to test if any of the features are significant we use the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT).

1. Wald test

Null hypothesis (\(H_0: \beta_j = 0\)): feature j has no effect on the outcome y. Alternate hypothesis (\(H_0: \beta_j \neq 0\)): feature j has some non-zero effect on the outcome y.

Test statistic:

\[W_j = \frac{\hat{\beta}^2_j}{\text{SE}(\hat{\beta}^2_j)}\]\(W_j\) is the squared Wald statistic and follows a chi-square distribution with 1 degree of freedom. While Wald follows a standard normal distribution, it’s generally approximated by the chi-square distribution. A large value indicates the null hypothesis is unlikely (coefficient is significantly different to 0). To assess the statistical significance, we compare this to a critical value from the chi-square distribution and compute the p-value:

- Set the significance level \(\alpha\), just like with the confidence interval (typically 0.05 or 95% confidence).

- Critical W: The value of the chi-square distribution that leaves an area of α (alpha) in the upper tail of the distribution (or α/2 in each tail for a two-tailed test). This can be found using the cumulative distribution function (CDF) or reference chi-square tables.

- If the absolute W-statistic exceeds the critical W-value, then we reject the null hypothesis. It’s uncommon we would see a \(\beta_J\) this large by chance.

- p-value: The area under the chi-square distribution curve with 1 degree of freedom (since we are testing a single coefficient) beyond the observed test statistic \(W_j\) (i.e. how often we see samples with values greater than or equal to this). For a two-sided test, double the area to account for both directions of the test. If the p-value is less than or equal to our chosen alpha, we reject the null hypothesis (it’s uncommon we would see a \(\beta_J\) this large by chance). If it’s greater than alpha, we can’t reject the null.

- The larger the absolute value of the W-statistic, the smaller the p-value will be and vice versa.

2. Likelihood ratio test (LRT)

The likelihood ratio test (LRT) can be used to test the significance of one or more coefficients by comparing the log-likelihood of the full model with that of a restricted model (in this case the null model).

\[H_0: \beta_1 = \beta_2 = \cdots = \beta_k = 0\] \[H_1: \text{At least one} \, \beta_j \neq 0\] \[\text{LRT Statistic} = -2 \left( \log(\text{L}_0) - \log(\text{L}_1) \right)\] \[\text{p-value} = P(\chi^2_k \geq \text{LRT Statistic})\]Where:

- \(\log(\text{L}_0)\) is the log-likelihood of the null model (a model with only the intercept term)

- \(\log(\text{L}_1)\) is the log-likelihood of the fitted model (the full model with all predictors)

- \(\chi^2_k\) denotes the chi-square distribution with k (number of features) degrees of freedom

As with the Wald test, we compare the LRT test statistic to the critical value, or check if the p value is less than alpha to determine whether we accept or reject the null hypothesis. E.g. if the p-value is less than alpha, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that at least one of the coefficients is significantly different from zero, suggesting that the predictors collectively contribute to explaining the response variable.

Extensions

While basic logistic regression is for binary classification, it can be extended to multiclass problems using a technique called multinomial logistic regression or softmax regression. In this case, instead of a single sigmoid function, we use the softmax function to handle multiple classes.

Summary

Logistic regression is a powerful technique for modeling binary outcomes, where the goal is to estimate the probability of a specific event occurring. It uses the logistic (sigmoid) function to map the linear output to a probability between 0 and 1. While it’s widely used in practice due to its simplicity and interpretability, logistic regression relies on certain assumptions, such as linearity in the log-odds and independence of observations. One limitation is that it may not perform well in the presence of high multicollinearity or when the sample size is small. To estimate the coefficients, logistic regression uses Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), which is computationally intensive and requires iterative optimisation.

Although more complex models (e.g. Random Forest, XGBoost) might outperform it in terms of predictive accuracy, logistic regression still provides valuable insights into relationships between features and binary outcomes. However, as with any observational model, care must be taken when making causal claims due to the potential for unmeasured confounding. Despite this, logistic regression remains a useful tool for hypothesis generation and for cases where interpretability is essential.

A subtle but important point is that the magnitude of logistic regression coefficients can change depending on which covariates are included: adding variables reduces the residual variation in the latent propensity, which typically increases the magnitude of other coefficients. This does not represent bias in the classical sense, but it does mean that odds ratios are sensitive to model specification, making direct causal interpretation more nuanced.

References:

- Stoltzfus, J.C. (2011), Logistic Regression: A Brief Primer. Academic Emergency Medicine, 18: 1099-1104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01185.x

- Giles, D. (2013), Robust Standard Errors for Nonlinear Models