Trustworthy online experiments

Some time ago I read the book Trustworthy Online Controlled Experiments: a practical guide to A/B testing by Kohavi, Tang, and Xu. I was pleasantly surprised by how practical it was! The authors have collectively worked at Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and LinkedIn, so they had a lot of great real life examples of both success and failure. While they don’t go deep, they have a nice coverage of many topics that you usually won’t find outside internal company guides. I’ve summarised my learnings from the book, with the addition of my own experience in some areas for me to refer back to.

Background

Motivation

It’s hard to guess which changes will be successful, and the successes are usually small incremental gains. By reducing the overhead, tech companies have made it possible for almost anybody to test an idea. Every now and then, someone gets lucky and a small change has a massive effect. At Bing, adding some of the description to the headline of an ad turned out to generate a $100M/year. Similarly, despite a VP being against it, personalised recommendations based on a user’s cart turned out to be very profitable for Amazon. They were then able to improve on the original ‘people who bought X bought Y’, by generalising it to ‘people who viewed X bought Y’, and later ‘people who searched X, bought Y’. Another area that’s been shown again and again to have a positive effect on many metrics is performance improvements (e.g. speeding up page load can increase sales).

However, don’t get too excited, you shouldn’t expect a large number of your experiments to succeed like this. It can also go the other way, for example Bing expected integrating with social networks would have a strong positive effect. After two years of experimenting and not seeing value, it was abandoned.

Why do we need randomised experiments?

Imagine we launched a new feature and observed users who interacted with it. Maybe those users are 50% less likely to churn than those who didn’t interact. Does that mean our feature causes less churn? We can’t say anything about the effect of the treatment on churn. The users self selected into the the treatment, and therefore are unlikely to otherwise be comparable to those who didn’t. Perhaps heavy users are more likely to interact with the feature, and thus they naturally have a lower churn rate (regardless of whether the feature is there or not).

In it’s simplest form, an experiment solves this by randomly splitting users into two groups: one sees no change from normal (control), and the other sees some new feature or change (variant). User interactions in both groups are monitored and logged (instrumented). Then at the end of the experiment, we use this data to assess the differences between the two groups on various metrics. By randomising which users are exposed, we know that the only difference between the two groups is due to the change (plus some random variation). This is why experiments are the gold standard for establishing causality, and sit near the top of the hierarchy of evidence.

When possible, a controlled experiment is often the easiest, most reliable and sensitive mechanism to evaluate changes. We’re only able to measure the effect of being exposed (some may not even notice the change), but this is generally enough to guide product development. Experiments can also be great for rolling out features because they provide an easy way to roll back if there’s issues.

Tenets for success

It help a lot if a company meets the following criteria:

- 1) They want to make data-driven decisions and have quantifiable goals. There is a cost to experimentation and it will slow down progress. It’s a lot easier to make a plan, execute on it, and declare success. However, this doesn’t change the true effect. To paraphrase Lukas Vermeer, you might run faster blindfolded because you don’t see the wall coming, but you’re still going to hit the wall. It’s also necessary that the goals are actually quantifiable (measurable in the short term, sensitive to change, and predictive of longer term goals).

- 2) They’re willing to invest in infrastructure and tests to ensure the results are trustworthy. In large established companies it’s relatively easy to get numbers, but hard to make sure they’re trustworthy. In other industries, even being able to run experiments reliably may be difficult/illegal/unethical; and,

- 3) They recognise that they are not good at evaluating the value of ideas. This is a hard one for some to accept. Team’s build features and make changes because they think it will add value. However, based on the experience of many companies (including Microsoft, Google, Slack, and Netflix), you should expect 70-90% of your tests to fail to detect any effect. The more optimised the product becomes, the harder it gets to move the needle. That’s why it’s important to fail fast, and test for signals first (e.g. before building a complex model for some feature, test the idea with some simple business logic first).

These can develop over time, and chapter 4 of the book has some good advice on the stages of maturity and what to focus on if you’re in the earlier stages.

Part 1. Pre-experiment design

General set up

Once you understand the hypothesis and treatment (e.g. what is the mechanism by which we expect to see an effect), below are some of the questions to think about:

-

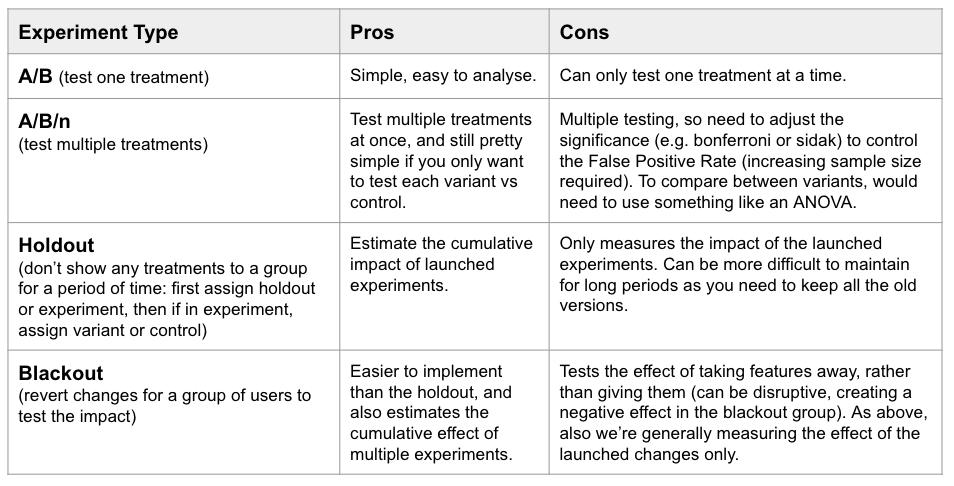

What kind of set up do we need? A/A (to get some data, or test our setup is working), A/B (one variant), A/B/n (multiple variants), or a holdout/blackout design.

-

What is a good control? Sometimes a treatment combines a visual change with some logic, so it’s important to isolate what is causing the effect. For example, let’s say we add a block to the top of the page with a special offer. The block pushes down other content, which likely has an effect regardless of the content. In this case we might do: control (no block), variant 1 (block with just a header title or something neutral), variant 2 (block with the offer). If both variants are negative vs the control, the block is likely damaging and the offer isn’t enough to offset it. This also comes up with testing models (e.g. adding an icon based on the prediction, in which case we might also want to test adding an icon based on simple logic or at random), and with ads (e.g. changing the layout might increase/decrease ads, which itself probably has a large effect regardless of the treatment).

-

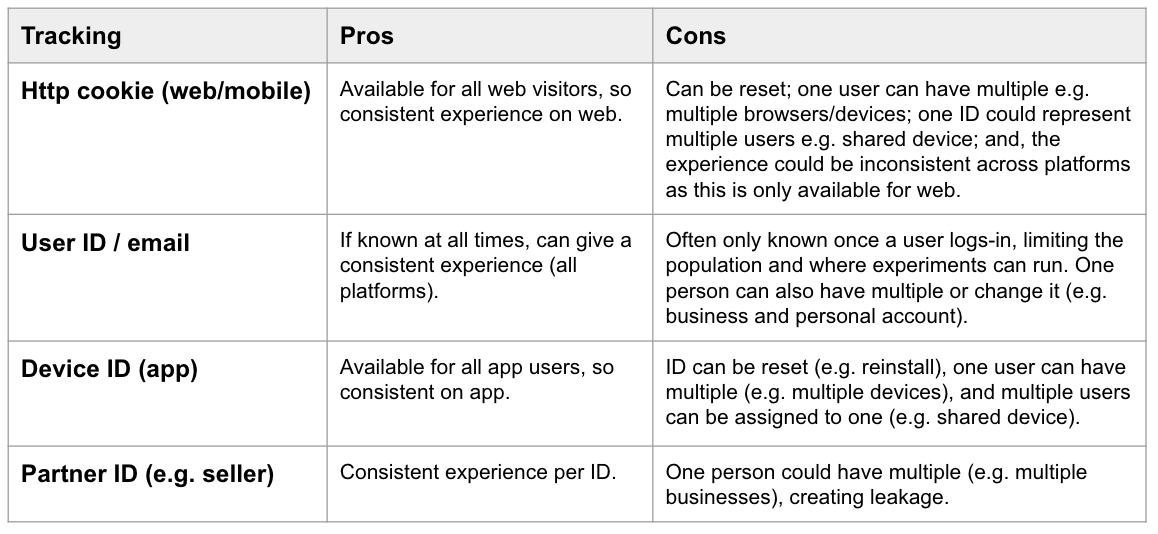

What unique ID will be used for tracking (the randomisation unit)? SUTVA (stable unit treatment value assumption) states the observations should be independent, so we want an ID that will avoid leakage or interactions between users. At an organisation level, you also need to decide what to do with abnormal users and bots (e.g. show base and exclude them, or still allocate at random but exclude them). Also keep in mind that all of your metrics should be done on the same level as the randomisation (e.g. if you randomise by cookie, your metrics will be something like average revenue per cookie).

-

How/where/when will visitors enter the experiment? Proper randomisation is critical, and it’s not as simple as it seems. The book goes into some depth on this. However, it’s already good just to be aware that it’s important, and look out for ways factors could influence the allocation. For example, when and where visitors enter the experiment can be a problem if they are in some way already exposed or influenced (e.g. tracking users who completed a purchase would not be a good choice for a change on the checkout page, as the change likely impacts the probability of purchasing). We also don’t want to over-track visitors as this adds unnecessary noise, and can drag the average effect towards zero if the metric is not possible for these users, in both cases reducing power. For example, including all visitors when only those who log-in are exposed. Similarly, under-tracking is also an issue, as some observations are lost. If it’s not at random, the sample no longer represents the population well.

-

What size effect is meaningful and how certain do we need to be? This is where the power analysis comes in. It’s important that we control error rates by deciding the runtime upfront. Sometimes the required runtime is too long, in which case we need to re-evaluate and trade-off the confidence or size of the effect we can detect. More on how to do this here.

-

How safe is the experiment? If we’re unsure about the implementation or how users might react, we might want to ramp up the experiment, starting with a small proportion of traffic and slowly increasing to the planned split.

-

Do we need to be mindful of other experiments? If we have other changes we want to test that might interact, we could run them at the same time, splitting the traffic. Or, we could wait, and test them one by one. For example, if one experiment removes a feature while another changes the feature, there’s an interaction and neither properly measures it’s intended effect. This is particularly bad in changes that a user can see (e.g. one experiment changes the background color while another changes the text color).

The above should then be wrapped up into a clear experiment plan and hypothesis. E.g. a good example hypothesis from the book is “Adding a coupon code field to the checkout page will degrade revenue per user for users who start the purchase process”.

Deciding Experiment Metrics

Measure a salesman by the orders he gets (output), not the calls he makes (activity) – Andrew Grove

Decide which metrics are important before the experiment starts to avoid the temptation of building a story around the results (which might be False Positives). They should be quantifiable, measurable in the short term (during the experiment), and sensitive to changes within a reasonable time period. Typically there will be a small number of “primary” metrics, some “secondary” metrics to help understand the primary movements, and guardrail metrics (e.g. monitoring things like performance).

Overall Evaluation Criteria (OEC)

In the book they talk about the concept of an OEC, which (potentially) combines multiple metrics, to give a single metric that’s believed to be causally related to the long-term business goals. For example, for a search engine, the OEC could be a combination of usage (e.g. sessions per user), relevance (e.g. successful sessions, or time to success), and ad revenue metrics. It could also be a single metric like active days per user (if the target is to increase user engagement). To combine multiple metrics, they can first by normalised (0-1), then assigned a weight. This will require definition of how much each component should contribute. For example, how much churn is tolerable if engagement and revenue increase more than enough to compensate? If growth is a priority, there might be a low tolerance for churn. In practice, you will still want to track the components as well to understand movements.

OEC Examples (goal -> feature -> metrics)

- Amazon emails: Originally the team used click-through revenue, but it caused spamming (optimising short term revenue only as users unsubscribed). By including a lifetime loss estimate for unsubscribing of even a few dollars they found more than half of their campaigns have a negative effect. \(OEC = \frac{(\sum_i{revenue_i - unsubscriber * \text{lifetime loss}})}{n}\)

- Bing: At Bing, progress is measured by query share and revenue. However, a ranking bug that lowered the quality of results actually increased both, as users were forced to do more queries and clicked more ads (results). Using sessions per user would be better in this case as satisifed users will return and use Bing more. This demonstrates what can happen when revenue metrics are used without constraints/guardrails. For ads, one way to enforce a constraint is to limit the average number of pixels that can be used over multiple queries.

- New features: Click-throughs on the feature won’t capture the impact on the rest of the page, so could allow cannibalisation. A whole page click-through metric would be better (penalised for bounces), along with conversion rate (successful purchase), and time to success.

How to evaluate metrics

- For new metrics, what additional information are we adding?

- For old metrics, periodically check if they’ve encouraged gaming (is there a notable behaviour of moving metrics just over the threshold), and whether there are any other areas for improvement.

- For both new and old, are the statistical assumptions still met. See my post here on how to do this.

- Verifying the relationship between drivers and goals is also important, but usually difficult. Some methods for this include: checking if surveys / user research / careful observational analysis / external research mostly seem to point in the same direction; running experiments specifically to try test different parts; and, using a set of well understood past experiments to test new metrics.

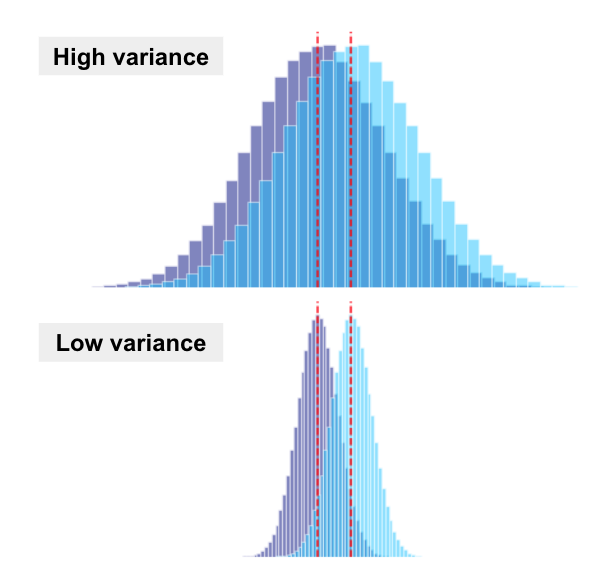

Improving sensitivity with variance reduction

At this point, you may have identified some important metrics, but they’re under-powered. One way we can improve the power of a test (sensitivity), is by reducing variance. When variance is reduced, there’s less overlap between the distributions of control and variant, making the effect more clear.

Ways to reduce variance:

- Use a binary metric: If still aligned well with the hypothesis, we could use a binary metric instead of a high variance continuous one. E.g. the number of searches has a higher variance than the number of searchers (1 if any search made, else 0). Similarly, Netflix uses a binary indicator of whether the user streamed more than X hours in a time period instead of measuring average streaming hours.

- Cap/winsorize/transform: If your metric is prone to outliers (unrelated to treatment), winsorizing (capping) values at some percentile will reduce variance (e.g. find the 1st and 99th percentile for the combined data, then cap values above/below those in both samples).

- Use stratification: Divide the population into strata (e.g. based on platform, browser, day of week, country), then sample within each stratum separately, combining the results for the overall estimate. When sampling, we expect some random differences between the groups, so this is a way to reduce the differences (reducing variance). This is usually done at the time of sampling, but can also be done retrospectively during the analysis.

- Use covariates: Let’s say you’re at Amazon and you want to increase supply. You might run an experiment where you incentivise shops to add new products, and use the number of products per shop as a success metric. Before entering the experiment, some shops have only a few products, while others have thousands. Controlling for their pre-treatment number of products likely reduces the variance, increasing power and our ability to detect smaller effects. We do this by fitting a regression, controlling for data known pre-experiment. The variance from pre-experiment factors is unrelated to the treatment, so we can safely remove it without introducing bias. The Microsoft experiment team developed the method CUPED (Controlled-experiment using Pre-Experiment Data) for exactly this (paper, and an article on how Booking.com uses this method. Ideally, the covariate is the same as the experiment metric but measured on the pre-experiment period (as the variance reduction is based on the correlation between the covariate and the metric).

- Use a more granular unit of observation: If possible, using a more granular ID will increase the sample size substantially (e.g. instead of user, you could use page views or searches). However, this is often difficult to do without any interaction or leakage (e.g. changing a page could have flow-on effects for the user’s experience on other pages).

- Paired experiment: If it’s possible to test both variant and control for the same user, a paired design will remove the between-user variability. For example, we can test two ranked lists at the same time with a design called interleaving (see this Netflix post for examples).

- Pooled control group: If you have multiple experiments running at the same time, each with their own control group, you might be able to combine them to increase the sample size and power.

Part 2. During the experiment

There can be a number of issues that pop up during an experiment. Usually they are around instrumentation, randomisation, ramping, or concurrent experiments. Monitoring and alerts are useful here to catch the problems early (e.g. test for a significant difference in the size of the control/test samples). I might come back to write on this in the future, but for now I’m mostly skipping over the topic to focus on where I spend the most time.

Part 3. Post experiment analysis

In the A/B case, we have two independent random samples, and summary statistics for each of our metrics in each group. Comparing the means gives us an estimate of the average treatment effect (ATE) in the population. By chance, we expect some random variation between the two groups, and so the observed difference will vary around the true effect in the population (i.e. even if the null is true and there is no efect, we will still observed differences). Therefore, it’s important we correctly estimate the standard error (how much we expect estimates to vary with repeated sampling), so we can assess whether a difference is ‘large enough’ for us to reject the null hypothesis. To do this, we compare the observed difference to the range of values we would observe if the null was true (so assuming the null is true, how likely is it we would observe a difference at least as extreme as this). If the result is surprising, we reject the null and conclude there is likely an effect (the result is significant).

Which test to use?

In general, the t-test or Welch’s t-test is most common for comparing means, and a z-test or g-test for proportions. For binary metrics, see here, and for continuous metrics see here. For ratio metrics, and comparisons of the percentage change (also a ratio), the variance is not the same as that of an average. In these cases, the Delta method can be used, or alternatively bootstrapping (see this post).

Common issues:

- Twyman’s Law: The more unusual or interesting the data, the more likely it is there was an error (i.e. errors such as logging issues, calculation errors, or missing/duplicated data are more common than truly large effects). Always treat those ‘too good to be true’ results with a healthy dose of skepticism.

- Lack of power: Often people will pick a standard runtime like 2 weeks without calculating the sample required for the effect size they’re interested in. This can lead to under-powered experiments with little chance of detecting effects, even if meaningful effects exist. I think it’s better to know this upfront, and trade-off your choices. More on this topic here.

- p-values: Related to the above, a non-significant p-value is often incorrectly interpreted as meaning there is no effect. In reality, we can’t prove an absence of an effect, and it’s also possible the effect was just too small to detect with this test. Another common mistake is to think it’s the probability the null is true (again false). The p-value assumes the null is true, then tells us how often we would expect a result at least as extreme as that observed. If it’s unlikely, we take that as evidence towards the alternate being true. A lot more on this topic here.

- Confidence intervals: Similar to the p-value, confidence are also often misinterpreted. Though generally it’s enough for stakeholders to understand it’s a range of plausible values for the true population effect. More on this in this post.

- Peeking at p-values: It’s not uncommon for people to monitor running experiments, including the p-value results. To control the error rates, we pre-determine the runtime, and it’s important that we wait till the end of the runtime to make a decision. The p-value can fluctuate, so stopping early (or later) when you see it’s significant will increase the False Positive Rate. If this is unsatisfying, you can also consider sequential testing, but it’s a lot less common in practice.

- Multiple testing: When one test is inconclusive, it’s tempting to try other metrics, definitions, or segments to see if there was any effect. However, the more tests we run, the higher our false positive rate becomes. For example, if the FPR per test is 5% and we run 20 tests, the probability of at least one False Positive become 64.2% (see this post for the workings). One approach for experiments is to separate metrics into 3 groups with descending significance levels based on priority (e.g. primary can be 0.05, secondary 0.01, but third order should 0.001). The logic is based on how much we believe the null is true pre experiment. The stronger the belief, the lower the significance level you should use.

Analysing segments

The effect of an experiment is not always uniform (i.e. there are heterogeneous treatments effects), so it can be useful to break down the results for different segments. For example, market or country (e.g. could be different reactions by region, or localisation issues), device or platform (e.g. web/mobile/app, iOS/Android, and browser breakdowns can help with spotting bugs), time of day and day of week (plotting effects over time), user characteristics (did they join recently e.g. within last month, account type (single/shared, business/personal)). Some considerations:

- Think about whether the sub-segments are comparable, as sometimes the differences may not be due to the treatment (e.g. the click through rate can differ for different operating systems because of different tracking technologies);

- Use the pre-treatment values as users might change segment due to the treatment (this is particularly common if the variable is based on a model);

- Avoid comparing segments that are not on the same unit as the randomisation (e.g. cancellation rate of bookers when you randomised visitors). These groups are not comparable anymore because you’ve shifted some users from “non-bookers” to “bookers” in the treatment group, but the comparable users in the control (the non-bookers who would be bookers with treatment) are being excluded.

- Correct for multiple testing. Alternatievly, one way to deal with this is to do many breakdowns (which could also be done with ML, e.g. a decision tree), identify and explore those that are interesting, and then validate them in a new experiment or with other methods on new data.

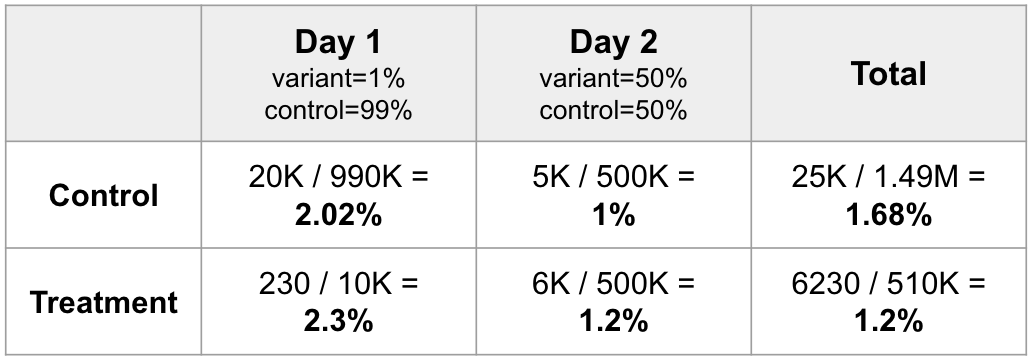

- Simpson’s paradox (different directions of association between small groups and the overall totals): This happens when we compare a treatment across two groups, and the proportions are not equal (e.g. doctor A treats more hard cases than doctor B, so even though doctor A has a higher success rate for both hard and easy cases, when the data is aggregated doctor B appears more successful). We can see this in experiments when the sampling ratio is different for different segments, or when ramping is used. For example, if we start with 1% in variant, then the next day increase to 50% in variant, even if the CR is higher in variant on both days, the table below shows how we end up with an overall negative effect (as day 1 counts more towards the control total). The problem is a higher proportion of the treatment observations are in day 2, and the conversion rate was in general lower on day 2.

Example from: Kohavi et al., chapter 3

Example from: Kohavi et al., chapter 3

Making a decision

Our goal is to use the data we’ve collected to make a decision, to ship the change, or not to ship.

Considerations:

- Metric trade-offs: The direction of the effect can differ across metrics, meaning we need to make some trade-offs. E.g. if engagement metrics improve, but revenue decreases, should we ship? The answer will depend on the goals of the test, and by how much each changes.

- Do the benefits outweigh the costs: We need to consider the cost of fully building out the feature (if not yet complete, e.g. MVP), and the potential maintenance costs (e.g. are we adding complexity that could cause more bugs in the future, or make it harder to change).

- Downsides of making a wrong decison: For example, if the change is temporary (like a limited time offer), then the cost of making a mistake is limited and we might set low bars for statistical and practical significance.

Potential outcomes:

- Result is not statistically or practically significant: Iterate or abandon the idea. If the bounds are very wide, you likely don’t have enough power to draw a strong conclusion. Consider running a follow-up experiment with more power.

- The result is practically significant, but not statistically significant (the change could be meaningful, or not exist at all). Like in the previous case, we would need a follow-up experiment with more power.

- Result is statistically and practically significant: Launch.

- Result is statistically significant, but not practically significant: May not be worth launching, consider costs. If the bounds are wide (could be practically significant, could not be), then like before we can retest with more power.

Other topics

Measuring long-term effects

Measuring long term effects is always a challenge given we typically want to launch a successful change as soon as possible. There are two common approaches:

- Proxies: Use short term metrics that are correlated with long term outcomes. For example, maybe 2 week retention is a good predictor of 1 year retention and so we can make our decision based on the 2 week result. Just give some thought as to whether you’re treatment could notably change the relationship between the short and long term metrics you’re using.

- Holdouts: These are typically 6 or 12 month long experiments where you hold out a small % of your population from 1 or more launches to see the long term effect. Maintenance is the main downside here as holdouts can be corrupted by unexpected errors that render them unusable. It’s also important to consider network effects between the holdout users and other users that might cause leakage (resulting in either an over or underestimated effect).

Opt-in products

Delayed Activation (e.g. opt-in products): Usually you would randomise assignments for some recruitment period, and then continue to observe for some observation window to give time for people to activate. Otherwise you might underestimate the effect size as newer users haven’t had time to activate. In addition to overall metrics, it’s useful to check the results based on days since activation to see if there’s any.

Experiments with an expected impact on performance

Sometimes we expect a new feature will negatively impact performance (e.g. calculations are required before showing the page, slowing down the page load). Before we spend time optimising a feature to address the performance impact though, we first want to know if it has any value. One way to separate the effect of the performance from the effect of the feature is to add a variant that does the calculations but doesn’t show the change:

- 1) control (no change);

- 2) variant 1 (do the calculations etc., but then don’t show the change), and

- 3) variant 2 (do the calculations etc., and show the change).

The difference between the control and variant 1 is the effect of any performance loss (as the only difference is the calculations etc. being done in variant 1). The difference between variant 1 and variant 2 gives us the effect of the feature (assuming no performance impact), as both should have the same performance. Finally, the difference between variant 2 and the control is the total effect of switching to this feature (including the effect of any performance change). If this total effect is positive, any performance loss is outweighed by the effect of the feature and so we could ship the change. However, if the total effect is negative, but the feature effect is positive and the performance effect is negative, we’ll need to work on optimisations to address the performance issues.

Threats to validity

Particularly if you were not involved in the experiment design stage, it’s worthwhile thinking about whether there could be any issues with the validity of the results. This can be broken into internal, external, and statistical validity:

1) Internal validity (truth in the experiment):

Does it measure what we intended to measure? Experiments control for confounders by randomising the treatment, but there are some common issues that might still make us question the internal validity:

- Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA) violation. For most tests we assume the observations are sampled independently: they don’t influence each other, each is counted only once, and each is only given one treatment. This can be violated for example if there’s a relationship between customers (e.g. in social networks a feature might spillover to their network), the ID is not unique (e.g. http cookies can be refreshed), or the supply is in some way shared between the control and variant (e.g. if you lower the price in variant, this likely lowers supply in control).

- Survivorship bias. This is about capturing all observations. A common example is the military looking at where returning planes had the most damage, with the intention of understanding where to add armor. However, it might actually be best to add armor to the places not damaged (as the planes damaged in those locations didn’t make it back).

- Self-selection. We often can’t control whether a user actually interacts with a treatment (e.g. we can send an email, but we can’t make someone open it). It might be tempting to only analyse those who actually interacted, but this decision is non-random meaning those who interact are likely different to those who didn’t. Instead we measure the effect of the intention to treat (e.g. being sent an email).

- Sample Ratio Mismatch. Sometimes due to errors in the design or setup, the ratio of users in control and variant doesn’t match the intended split (e.g. bots, browser redirects, and lossy instrumentation could be to blame). Even a small imbalance can completely invalidate the experiment, but don’t just eyeball, use a test like demonstrated in this SRM checker. If there’s an SRM, you’ll need to investigate, correct, and restart.

- Residual effects. Often bugs are identified when an experiment is first launched, and the experiment is continued after fixing. Be wary that those users could still return and be impacted by their earlier experience. Re-randomising redistributes the effect, but it might be best to leave some buffer between the experiments to ensure there’s no residual effects.

2) External validity (truth in the population): Can the results be generalised to new people/situations/time periods beyond what was originally tested? Some of the key threats to this are:

- Primacy and novelty effects. Users are ‘primed’ on the old feature, so it may take time for them to adjust to the new feature (need to run for long enough). Novelty effects are the inverse: users are initially intrigued by the new feature, but the effects wear off over time. To detect these plot usage over time, as well as the effect over time based on when users joined (x would be days since exposure, y is the metric). We generally assume the effect is constant over time, so if it’s increasing/decreasing we may need to run longer to see if it stabilises.

- Seasonality. If you run the experiment during an ‘unusual’ time (e.g. Christmas), the observed effects may not generalise to other time periods. For example, at Bing, purchase intent rises dramatically around December, and so ad space is increased, and revenue (per search) increases. It’s generally advised to avoid testing new features from around mid December until after the new year for this reason.

- Hour/day seasonality or variations. You generally want to run an experiment for at least a week as users can behave very differently depending on the day of week. Taking the average over the week (or usually two weeks) gives a more generalisable result.

- Population changes combined with heterogeneous treatment effects. For example, if the effect differs by country and the mix of countries changes for some reason (e.g. product temporarily blocked by government), this would change the average treatment effect. Though, if you want to test on a completely new country/product/etc., it’s usually easy enough to just re-run the experiment.

- Changes in the effect of a treatment: e.g. the requirements and behaviours of customers can change drastically due to an external shock like a pandemic. Re-starting the experiment, or carefully excluding the event are options.

3) Statistical validity: Were appropriate statistical tests chosen (usually built-in to the company tool), and the assumptions of the test(s) met?

Strategy decisions

When goals can be measured with well defined metrics, experiments can help companies “hill climb” to a local optimum. However, if you want to try something far from the current, it takes more resources to get an MVP and it’s more likely to fail. This is because testing big changes in experiments requires longer and larger experiments (more likely to have primacy/novelty effects), and you may need many experiments to isolate what is and isn’t working. That said, experiments can still help reduce the uncertainty and provide gaurdrails for changes. Beyond that, a useful question to consider is “how will additional information help decision making?”.

When not to experiment?

Sometimes a decision needs to be made, and an experiment is simply not practical. For example: the population of users is too small and you would have to run the experiment for an impractically long time; you’re retention period for the ID is limited so you can’t run the experiment long enough; or, there are legal/ethical reasons. Experimentation is just one tool in the toolbox, and sometimes qualitative approaches make more sense (e.g. usability tests, interviews), or a quasi-experiment methodology can be useful (e.g. a geo experiment randomising at the country/region level, or randomising time instead of users).

Estimating the cumulative impact of experiments

To calculate team impact, some still add up the estimated average effect for a target metric across all the experiments that they decided to launch. This assumes each launch is additive (independent), and the effect is stable over time. However, even with those assumptions it will over-estimate the effect due to m-error. This post explains it well, but essentially we truncate the distribution of effect sizes by imposing a significance threshold. If teams run under-powered experiments, the over-estimation will be worse.

Two better options are:

- Holdout: Running a longer term holdout with all the launches (as discussed above) will measure the cumulative effect.

- Blackout: Removing multiple launches for some period. Only suitable for cases where the effect of removing the features would be similar to the effect of adding it, and there’s no interaction issues.

- Replication: Re-run successful experiments to get the effect size estimate. Called a certification experiment in the example given in the book.

Conclusions

I’ll finish with a quote that resonated with me:

Good data scientists are skeptics: they look at anomolies, they question results, and they invoke Twyman’s law when the results look to good. (Kohavi et al,. Chapter 3)